The Statewide Landcover and Trees Study (SLATS) monitors woody vegetation extent, and changes to that extent due to clearing and regrowth using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery as its primary monitoring tool.

The 2021–22 SLATS reporting period is nominally from August 2021 to August 2022. A range of data summaries which analyse the clearing and regrowth data with other key data sets of interest are presented in the report. Regional summary data for bioregions are also included.

The 2021–22 SLATS report and data are directly comparable with SLATS reports published from 2018–19 onwards. Published SLATS reports for reporting periods up to and including 2017–18 are not comparable with reports published from 2018–19 onwards, due to a change in methodology.

With an area of approximately 173 million hectares, Queensland is the second largest state in Australia. It is nearly five times the size of Japan and seven times the size of Great Britain. It is home to diverse flora and fauna due to its unique habitats which include extensive arid and semi-arid rangelands, and temperate, sub-tropical and tropical environments.

Queensland has more than 1,400 regional ecosystems with the majority of these described as woody regional ecosystems. These woody regional ecosystems include the sparse and very sparse shrublands and woodlands of the extensive arid and semi-arid rangelands, and the sparse woodlands and mid-dense and dense forests and rainforests along the Great Dividing Range, coastal plains, and in the Cape York Peninsula and Wet Tropics bioregions. These ecosystems play a critical role in supporting biodiversity, maintaining landscape function and water quality, supporting agricultural production, sequestering and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and providing recreation and natural amenity. To conserve, protect, and sustainably use these ecosystems in a changing climate, it is essential to have spatial and temporal data and information to characterise their composition and structure and to monitor their dynamics.

In Queensland, the regional ecosystems framework provides the basis for describing the vegetation types and their remnant status. The Statewide Landcover and Trees Study (SLATS) monitors woody vegetation extent, and changes to that extent due to clearing and regrowth, using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery as its primary monitoring tool. A Spatial BioCondition framework has also been developed to characterise and map the condition of the state’s regional ecosystems. Combined, these initiatives provide a spatially and temporally comprehensive account of Queensland’s ecosystems based on peer-reviewed science.

The current series of SLATS reporting monitors and reports change in woody vegetation extent against a woody extent baseline, first introduced in 2018 and updated annually based on mapping of woody vegetation clearing and regrowth. Additional scientific approaches have also been developed to attribute the degree of modification associated with the clearing activity and to provide estimates of woody vegetation density and age since disturbance. These approaches aim to better describe the woody vegetation that currently exists, and where and how its extent is changing.

The 2021–22 SLATS reporting period is nominally from August 2021 to August 2022. A range of data summaries which analyse the clearing and regrowth data with other key data sets of interest are presented in the report. Regional summary data for bioregions are also included.

The 2021–22 SLATS report and data are directly comparable with SLATS reports published from 2018–19 onwards. Published SLATS reports for reporting periods up to and including 2017–18 are not comparable with reports published from 2018-19 onwards, due to a change in methodology.

It is important to note that clearing activity mapped in remnant and high-value regrowth areas does not always result in a conversion to non-remnant. The Queensland Herbarium and Biodiversity Sciences uses SLATS data to inform remnant and high-value regrowth updates as part of regular regional ecosystem updates. These updates consider the clearing activity as well as a range of other criteria associated with the regional ecosystem mapping methodology, including the remnant and high-value regrowth definitions. For data and information on change in remnant vegetation, visit Remnant regional ecosystem vegetation in Queensland.

Note: There may be minor differences between SLATS reports and associated open data for the following reasons:

Note: Since the release of 2018–19 SLATS report, the methods for estimating the age since disturbance of woody vegetation have been revised and the spatial data has been updated for all years from 2018 onwards. It is important to note that the 2018 SLATS woody vegetation extent baseline report and the 2018–19 SLATS report remain as published at the time; age since disturbance figures in those reports are based on an earlier version of the age since disturbance data.

The SLATS age since disturbance estimates are based on time-since-cleared data derived from SLATS clearing histories, and time-series analysis of more than 30 years of Landsat satellite imagery aimed at detecting woody vegetation disturbance and regrowth. The age since disturbance estimates use the time-series information where sufficient evidence is available to assign a valid estimate of how long the woody vegetation has been regrowing following a disturbance event.

For more information on how the age since disturbance estimates are derived, refer to the SLATS methodology. It is important to note that woody vegetation that is greater than 15 years is not always considered to be remnant or high-value regrowth, as additional criteria such as species composition and vegetation height are used to determine remnant or high-value regrowth status. This is determined as part of the regional ecosystem mapping framework.

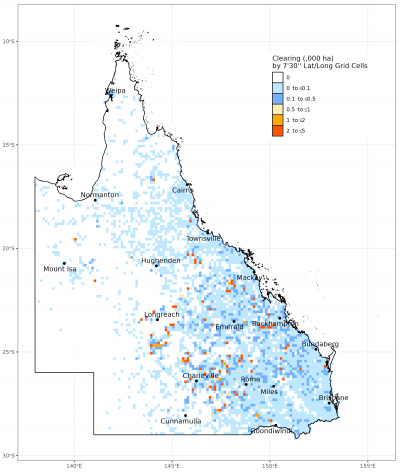

In 2021–22, a total of 323,676ha of woody vegetation was affected by clearing activity in Queensland. This is a 7% decrease in clearing activity from 2020–21 (349,399ha), which continues a trend of decreasing clearing activity in Queensland in the past few years. Of the total clearing activity 83% (269,432ha) resulted in full removal of the woody vegetation (i.e. full clearing). The remaining 54,244ha of clearing activity was partial clearing.

For more detailed breakdowns of clearing activity in the 2021–22 monitoring period, refer to the Statewide breakdown.

Area of clearing activity from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

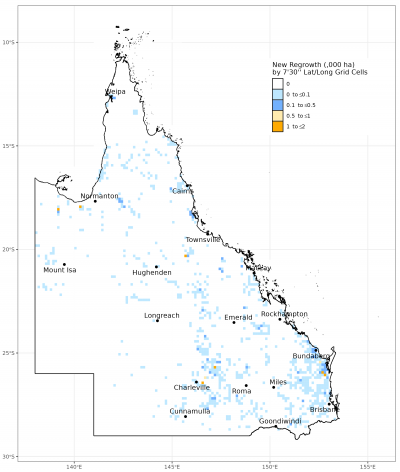

In the 2021–22 monitoring period, 31,097ha of new regrowth was mapped. These are areas that were not previously mapped in the 2018 woody vegetation extent baseline or in the last two monitoring periods (2019–20 or 2020–21) and are only now considered to have sufficient woody vegetation cover to be added to the woody extent. Given most of the existing regrowth was captured in the 2018 baseline, high levels of new regrowth would not be expected in the first few years to follow. This is due to the generally longer timeframes it takes for new regrowth to become sufficiently woody to enable reliable detection and mapping.

For more detailed breakdowns of regrowth in the 2021–22 monitoring period, refer to the Statewide breakdown.

Area of new regrowth from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

From a starting balance of 95,383,184ha, 269,432ha was subtracted for full clearing and 31,097ha was added for new regrowth. At the end of the 2021–22 SLATS monitoring period, Queensland had 95,144,850ha of woody vegetation. This represents a net reduction of 238,334ha in the extent of the state’s woody vegetation from 2020–21.

| Category | Gain (ha) | Loss (ha) | Balance (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening balance August 2021 | - | - | 95,412,788 |

| Adjustment | 5,530 | -35,134 | 95,383,184 |

| Crop | 1,484 | -1,680 | 95,382,988 |

| Forestry | 7,747 | -6,300 | 95,384,436 |

| Infrastructure | 0 | -2,207 | 95,382,229 |

| Mine | 489 | -5,885 | 95,376,833 |

| Pasture | 21,369 | -252,019 | 95,146,183 |

| Settlement | 8 | -1,341 | 95,144,850 |

| Closing balance August 2022 | - | - | 95,144,850 |

This transaction summary shows the opening balance of woody vegetation at the start of the 2021–22 monitoring period, the losses due to clearing activity that resulted in the full removal of the woody vegetation, and the gains due to new regrowth, for each landcover replacement class. Loss and gain adjustments were made to correct for areas in the woody extent that were identified as previous errors during the SLATS mapping processes. A closing balance at the end of the 2021–22 monitoring period is provided.

While these figures represent a net reduction in woody vegetation extent, it is important to acknowledge that not all vegetation change is equal. For example, clearing in remnant areas cannot be directly compared with clearing in non-remnant areas in terms of the impacts on biodiversity, carbon or landscape function. Similarly, new regrowth does not offset remnant loss for the same reasons.

In 2021–22, about 20% (65,776ha) of the statewide clearing activity was in Category B (regulated remnant) areas. This represents a 22% increase in clearing activity from 2020–21 (54,136ha). The Brigalow Belt (39% or 25,898ha), Mitchell Grass Downs (24% or 15,677ha) and Mulga Lands (11% or 7,483ha) bioregions had the highest areas of clearing activity in Category B areas. The Mitchell Grass Downs bioregion had a significant increase (98%) from 2020-21, in part attributable to a few larger clearing events on the southern margins of the bioregion. The Brigalow Belt also recorded a 16% increase in clearing activity in Category B. Some of this is attributable to partial clearing as part of forestry activities in state forests to the south of Carnarvon National Park, near the township of Injune. The Mulga Lands bioregion recorded an 18% decrease in clearing activity in Category B areas from 2020–21.

Of the clearing activity in Category B areas across the State, 62% (40,577ha) resulted in full removal of the woody vegetation. The remainder of the Category B clearing activity was distributed between areas that were partially cleared with a major level of disturbance (30% or 19,470ha) or partially cleared with a minor level of disturbance (9% or 5,727ha).

About 1% (3,624ha) of the statewide clearing activity was in Category C (high-value regrowth vegetation)—a decrease from 4,701ha in 2020–21. Less than 1% (1,607ha) of the clearing activity was in areas that intersect with Category R (regrowth watercourse area)— a decrease from 2,321ha in 2020–21.

Clearing activity in Category X areas accounted for 78% (252,538ha) of the total clearing activity—this was a 12% decrease from 2020–21 (288,165ha). About 89% (224,749ha) of this clearing activity resulted in full removal of the woody vegetation. Over half of the Category X clearing activity was in the Brigalow Belt bioregion (57% or 144,409ha) with a further 18% (45,638ha) occurring in the Mulga Lands bioregion. Category X areas are those that are not generally regulated by the Vegetation Management Act 1999, as identified in the Regulated vegetation management map.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

In 2021–22, about 18% (57,678ha) of the clearing activity was in areas that contained least concern regional ecosystems—this was an increase of 16% from the 49,850ha mapped in 2020–21. About 3% (9,924ha) of the clearing was in areas identified as having of concern regional ecosystems—a decrease of about 6% from 2020–21 (10,546ha). Less than 1% (2,508ha) of the clearing was in areas which have endangered regional ecosystems present—also a decrease from the 2020–21 figure of 2,714ha. The majority of this (76% or 1,902ha) was in the Brigalow Belt bioregion and around three-quarters (1,379ha) of this was full clearing.

The remaining 78% (253,566ha) was in areas with no vegetation management class. SLATS reporting applies the precautionary principle, with the highest vegetation management class used, regardless of the proportion present in regional ecosystem mapping. For example, where a mapped regional ecosystem contains least concern regional ecosystems as the dominant ecosystems, and an endangered regional ecosystem as subdominant, this will be reported as clearing in areas containing endangered regional ecosystems.

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

Of the state’s 13 bioregions, the Brigalow Belt (54% or 173,294ha) and Mulga Lands (17% or 53,345ha) accounted for nearly three-quarters (70%) of the state’s woody vegetation clearing activity. Both bioregions recorded decreases in clearing activity from 2020–21 continuing the downward trend from the previous year; the Mulga Lands decreased by 26%, while the Brigalow Belt recorded a 4% decrease. There has been a continued significant decline in clearing activity in the Mulga Lands recorded over the previous mapping eras, specifically between 2018–19 (284,648ha), 2019-20 (110,161ha) and 2021–22 (72,238ha).

About 95% of the clearing activity in the Mulga Lands and 77% in the Brigalow Belt resulted in full removal of the woody vegetation. The majority of the clearing activity in these two bioregions was in Category X areas, accounting for 83% (144,409ha) of the clearing in the Brigalow Belt and 86% (45,638ha) in the Mulga Lands.

Clearing activity in the Mitchell Grass Downs was 12% of the statewide total (39,720ha), Southeast Queensland was 6% (17,966ha) and Desert Uplands was 5% (15,204ha). Both Southeast Queensland and the Desert Uplands recorded a significant decrease in clearing activity (27% and 42%, respectively) from 2020–21. However, the Mitchell Grass Downs bioregion had a significant increase in clearing activity of around 49%, when compared to 2020–21 (26,671ha), partly due to a few larger clearing events in the southern part of the bioregion, some of which were mapped as partial clearing.

Area of clearing activity in bioregions in 2021–22.

The Southeast Queensland bioregion had the greatest area of new regrowth mapped, contributing 9,741ha to the state’s total of 31,098ha. The Brigalow Belt bioregion had the next greatest area of new regrowth mapped, contributing about 8,085ha to the state’s total.

Area of new regrowth in bioregions in 2021–22.

For further detailed breakdowns for each of the bioregions see further breakdowns by bioregion.

Clearing activity in the Great Barrier Reef catchment areas accounted for 44% (143,683ha) of the state’s total clearing—this was a 13% decrease in clearing activity from 2020–21 (164,766ha). About 79% (113,765ha) of the clearing in Reef catchments in 2021–22 resulted in the full removal of the woody vegetation.

Area of clearing activity in Great Barrier Reef catchments from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

In 2021–22, about 47% (14,529ha) of the new regrowth mapped in the state was in Great Barrier Reef catchments.

Area of new regrowth in Great Barrier Reef catchments from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

In 2021–22, 88% (286,108ha) of the clearing activity was attributed to the Pasture landcover replacement class— this was an 8% decrease from 2020–21 (310,339ha) for this class. Of this, about 88% (252,019ha) was full clearing. A further 5% (17,310ha) of the clearing activity was attributed to Forestry, 2% to Mine (5,885ha), and about 1% to Crop (1,680ha).

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in SLATS methodology.

About 69% (21,369ha) of the new regrowth mapped was attributed to the Pasture landcover class, and about 25% (7,747ha) was attributed to Forestry. A further 5% (1,184ha) was mapped as Crop, mainly due to new tree-crop orchards in parts of Southeast Queensland (Burnett-Mary) and the Wet Tropics (around Atherton) bioregions. Due to the difficulty of differentiating between native and non-native woody vegetation using satellite imagery, non-native woody vegetation change is also included in SLATS change mapping. This may include exotic pine plantations, orchards or invasive exotic woody weeds.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

In 2021–22, about 91% (294,841ha) of the total clearing activity occurred in sparse and very sparse woody vegetation (i.e. vegetation with less than 50% crown cover). This is reflective of a large proportion of the state’s clearing activity occurring in rangeland ecosystems including the Brigalow Belt, Mulga Lands, Desert Uplands and Mitchell Grass Downs bioregions, which are characterised by scattered trees and shrubs, open woodlands and shrublands. A further 9% (27,622ha) of the clearing activity occurred in mid-dense woody vegetation (i.e. 50–80% crown cover). Less than 1% of the total clearing occurred in dense woody vegetation (1,198ha).

Area of clearing activity for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Based on estimates of woody vegetation age since disturbance (refer to note), about 58% (187,762ha) of the total clearing activity in 2021–22 occurred in vegetation greater than 15 years old, and about 87% (163,523ha) of this occurred in sparse or very sparse woody vegetation.

About 30% (97,090ha) of the total clearing activity occurred in vegetation with an age since disturbance of less than 15 years, and most of this (97% or 94,303ha) occurred in sparse or very sparse woody vegetation. About 12% (38,823ha) of the clearing activity occurred in woody vegetation where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined.

Area of clearing activity for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

About 88% (27,610ha) of the regrowth mapped was categorised as sparse or very sparse woody vegetation. A further 11% (3,467ha) of the regrowth mapped was categorised as mid-dense woody vegetation and less than 1% (19ha) was in dense woody vegetation.

Of the 31,097ha of new regrowth mapped, 72% (22,484ha) was estimated to be less than 15 years old. 19,750ha of this was categorised as sparse or very sparse woody vegetation.

A further 15% (4,578ha) of the new regrowth mapped was estimated to be greater than 15 years old and about 90% of this was categorised as sparse or very sparse woody vegetation. The remaining 13% (4,036ha) of new regrowth mapped was in areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined.

For ‘older’ areas of new regrowth, either the age since disturbance estimate is unreliable or they may be areas that were previously excluded from the 2018 woody extent baseline. It is possible that given most of these are in sparser vegetation types, the vegetation may not have been readily detectable in the satellite imagery used at the time the 2018 baseline was mapped, and it has now become more readily detectable due to additional data in the time series or availability of other new imagery.

Area of new regrowth for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of new regrowth by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Note: Since the release of 2018–19 SLATS report, the methods for estimating the age since disturbance of woody vegetation have been revised and the spatial data has been updated for all years from 2018 onwards. It is important to note that the 2018 SLATS woody vegetation extent baseline report and the 2018–19 SLATS report remain as published at the time; age since disturbance figures in those reports are based on an earlier version of the age since disturbance data.

The SLATS age since disturbance estimates are based on time-since-cleared data derived from SLATS clearing histories, and time-series analysis of more than 30 years of Landsat satellite imagery aimed at detecting woody vegetation disturbance and regrowth. The age since disturbance estimates use the time-series information where sufficient evidence is available to assign a valid estimate of how long the woody vegetation has been regrowing following a disturbance event.

For more information on how the age since disturbance estimates are derived, refer to the SLATS methodology. It is important to note that woody vegetation that is greater than 15 years is not always considered to be remnant or high-value regrowth, as additional criteria such as species composition and vegetation height are used to determine remnant or high-value regrowth status. This is determined as part of the regional ecosystem mapping framework.

Area of clearing activity in bioregions in 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in bioregions in 2021–22.

Area of clearing activity in Brigalow Belt from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Brigalow Belt from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Brigalow Belt for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Brigalow Belt for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Brigalow Belt by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Brigalow Belt for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Brigalow Belt for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Brigalow Belt by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Channel Country from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Channel Country from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Channel Country for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Channel Country for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Channel Country by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Channel Country for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Channel Country for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Channel Country by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Central Queensland Coast from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Central Queensland Coast from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Central Queensland Coast for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Central Queensland Coast for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Central Queensland Coast by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Central Queensland Coast for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Central Queensland Coast for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Central Queensland Coast by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Cape York Peninsula from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Cape York Peninsula from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Cape York Peninsula for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Cape York Peninsula for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Cape York Peninsula by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Cape York Peninsula for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Cape York Peninsula for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Cape York Peninsula by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Desert Uplands from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Desert Uplands from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Desert Uplands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Desert Uplands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Desert Uplands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Desert Uplands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Desert Uplands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Desert Uplands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Einasleigh Uplands from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Einasleigh Uplands from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Einasleigh Uplands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Einasleigh Uplands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Einasleigh Uplands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Einasleigh Uplands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Einasleigh Uplands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Einasleigh Uplands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Gulf Plains from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Gulf Plains from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Gulf Plains for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Gulf Plains for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Gulf Plains by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Gulf Plains for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Gulf Plains for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Gulf Plains by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Mitchell Grass Downs from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Mitchell Grass Downs from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Mitchell Grass Downs for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Mitchell Grass Downs for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Mitchell Grass Downs by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Mitchell Grass Downs for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Mitchell Grass Downs for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Mitchell Grass Downs by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Mulga Lands from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Mulga Lands from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Mulga Lands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Mulga Lands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Mulga Lands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Mulga Lands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Mulga Lands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Mulga Lands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in New England Tableland from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in New England Tableland from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in New England Tableland for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in New England Tableland for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in New England Tableland by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in New England Tableland for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in New England Tableland for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in New England Tableland by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Northwest Highlands from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Northwest Highlands from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Northwest Highlands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Northwest Highlands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Northwest Highlands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Northwest Highlands for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Northwest Highlands for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Northwest Highlands by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Southeast Queensland from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Southeast Queensland from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Southeast Queensland for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Southeast Queensland for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Southeast Queensland by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Southeast Queensland for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Southeast Queensland for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Southeast Queensland by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Wet Tropics from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

Area of new regrowth in Wet Tropics from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Regulated vegetation management maps show the different vegetation categories that are present on a parcel of land. This information helps land managers determine the type of approval needed for vegetation clearing. The categories are as follows:

For further information refer to General guide to the vegetation clearing codes (PDF).

The vegetation management class refers to the current regulated extent of a regional ecosystem. The categories are endangered, of concern and least concern. No VM class refers to areas with no vegetation management class due to no regulated vegetation being present.

For further information refer to Biodiversity status and vegetation management class.

The landcover replacement class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. It provides an indication of the purpose for which the vegetation was cleared. Read more about this in the SLATS methodology.

The landcover class is determined as part of the SLATS mapping process. For new regrowth mapping it provides an indication of the purpose for which the land is used where the regrowth occurs. Read more about SLATS methodology.

Area of clearing activity in Wet Tropics for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of clearing activity in Wet Tropics for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Area of clearing activity in Wet Tropics by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Wet Tropics for density classes of woody vegetation.

Density classes are as follows:

Area of new regrowth in Wet Tropics for age since disturbance classes (refer to note).

Area of new regrowth in Wet Tropics by density and age since disturbance classes.

An age since disturbance of NASD (i.e. no age since disturbance) refers to those areas where a valid age since disturbance estimate could not be determined from SLATS clearing histories and/or time-series analysis of historical satellite imagery.

Density classes are as follows:

Note: Since the release of 2018–19 SLATS report, the methods for estimating the age since disturbance of woody vegetation have been revised and the spatial data has been updated for all years from 2018 onwards. It is important to note that the 2018 SLATS woody vegetation extent baseline report and the 2018–19 SLATS report remain as published at the time; age since disturbance figures in those reports are based on an earlier version of the age since disturbance data.

The SLATS age since disturbance estimates are based on time-since-cleared data derived from SLATS clearing histories, and time-series analysis of more than 30 years of Landsat satellite imagery aimed at detecting woody vegetation disturbance and regrowth. The age since disturbance estimates use the time-series information where sufficient evidence is available to assign a valid estimate of how long the woody vegetation has been regrowing following a disturbance event.

For more information on how the age since disturbance estimates are derived, refer to the SLATS methodology. It is important to note that woody vegetation that is greater than 15 years is not always considered to be remnant or high-value regrowth, as additional criteria such as species composition and vegetation height are used to determine remnant or high-value regrowth status. This is determined as part of the regional ecosystem mapping framework.

2021–22 SLATS Report, 17 Jul 2024, [https://oss-uat.clients.squiz.net/environment/land/management/mapping/statewide-monitoring/slats/slats-reports/2021-22-slats-report]

This document is uncontrolled when printed. Before using the information in this document you should verify the current content on https://oss-uat.clients.squiz.net/environment/land/management/mapping/statewide-monitoring/slats/slats-reports/2021-22-slats-report.