When complications occur Guide

-

Plans may change

Every woman is different. Every labour is different.

Sometimes pregnancy, labour and birth may not go as planned. The reasons are usually complex.

This module will discuss the following important topics:

- pre-eclampsia

- preterm birth

- multiple birth

- breech

- overdue pregnancy

- monitoring in labour.

- concerns for baby in labour

- antibiotics during labour

- blood loss after birth

Always talk to your doctor or midwife if you are concerned.

-

Pre-eclampsia

Symptoms of pre-eclampsia may include:

- high blood pressure and the presence of protein in the urine

- severe headaches

- sudden swelling, weight gain

- blurred vision or seeing ‘stars’ or ‘spots’

- a sense of feeling very unwell.

What is pre-eclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia is a serious disorder of pregnancy characterised by high blood pressure and serious complications of other organs in the body. Without treatment, seizures can develop. This can be fatal for mother and baby.

It is the most serious medical complication of pregnancy, affecting around five to 10% of all pregnancies in Australia. Researchers still do not know exactly why it happens in some pregnancies.

Regular antenatal checks are vital to keep a check on your blood pressure. Sometimes medication is needed. The onset of pre-eclampsia can be fast! If you experience any of the symptoms, seek medical assistance urgently.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Pre-eclampsia

-

Preterm birth

What is a preterm (premature) birth?

A preterm birth is one that happens before 37 weeks of pregnancy. In about half of all preterm births, the cause is unknown.

Factors that increase the likelihood of a premature birth can be:

- a previous premature birth

- some conditions of the uterus or cervix, such as fibroids or a weakened cervix

- a multiple pregnancy

- a maternal infection

- some maternal medical conditions such as pre-eclampsia.

If babies are premature, they are likely to need extra care at birth.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Preterm labour and birth

-

Breech

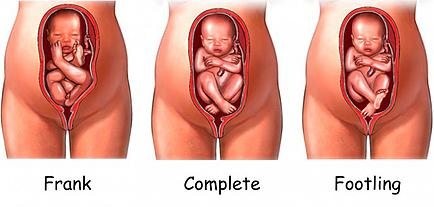

A breech position means the baby presents bottom or feet first, rather than head first.

During pregnancy, many babies are in the breech position. However, most babies turn before 37 weeks.

If your baby is still breech at 37 weeks, the chances of your baby turning by itself are low.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the implications of this for your birth plan and what options are available.

Your options may include:

- external cephalic version

- vaginal breech birth

- elective caesarean birth (usually performed after 39 weeks).

Breech vaginal birth

You may be suitable for a vaginal breech birth if:

- you go into spontaneous labour

- the estimated weight of your baby is within normal limits

- your baby is in either a complete (flexed) or frank (extended) breech presentation

- an ultrasound scan confirms your baby’s head is not extended

- the size and shape or your pelvis are adequate

- you have no pre-existing complications in your pregnancy.

Types of breech presentations

More information: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Breech presentation at the end of your pregnancy

External cephalic version (ECV) for breech presentation

ECV is a commonly practiced procedure with a low risk of complications.

ECV can reduce the need for a caesarean birth. The success rate is approximately 40% for first time mothers and 60% for others. If you choose to have an ECV, the procedure is done in hospital.

- A trained doctor gently turns the baby by placing their hands on your abdomen and gently coaxing the baby around so it can be born head first.

- This procedure is done at around 37 weeks, using ultrasound to help see the baby, cord and placenta.

What you need to know

Mother and baby are monitored during the procedure.

There’s a small risk that turning the baby may tangle the cord or separate the placenta from the uterus – in which case an emergency caesarean birth is needed. If the baby is still in the breech position at the end of pregnancy, a caesarean birth may be recommended.

More information:

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – External cephalic version (ECV)

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Breech presentation at the end of your pregnancy

-

What if my pregnancy is ‘overdue’?

Note: treat ‘home remedies’ with a dose of caution.

A simple internet search will give you countless results for ‘natural’ ways to trigger labour. Be sure to get your midwife or doctor’s OK before trying any home remedies, herbal supplements or alternative treatments.

Around 80% of babies are born between 38 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. This is often called ‘at term’. Babies born after 40 weeks are described as ‘post term’.

It's OK to feel frustrated or disappointed if your pregnancy has gone past its due date. Try not to worry, soon you'll hold your baby in your arms and the long wait will be over.

While you are waiting, stay in touch with your midwife or doctor. You'll need frequent check-ups until your baby is born.

Take advantage of the extra time. You may want to:

- get some extra sleep

- make any final preparations for baby

- stock your freezer with meals

- review your birth preferences.

Overdue pregnancy

If your labour hasn’t started by 41 weeks, your midwife or doctor will probably offer you a 'membrane sweep’.

What is a membrane sweep?

A membrane sweep involves a vaginal (internal) examination that stimulates the cervix (neck of your womb) to produce hormones that may trigger natural labour.

If your labour still doesn’t start naturally after this, your midwife or doctor will discuss with you a date to have your labour induced.

If your pregnancy lasts longer than 42 weeks there is a higher risk of complications.

Your doctor or midwife will probably recommend regular tests to check on your health and your baby’s health. After 42 weeks, there is a higher risk of stillbirth or fetal compromise.

These tests might include an ultrasound to check the amniotic fluid index and an ultrasound to check the biophysical profile.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Overdue

-

How will my baby’s heart rate be monitored during my labour?

Intermittent monitoring

If you have had a healthy pregnancy and there are no problems at the onset of labour, your midwife will listen to your baby's heart beat every 15 to 30 minutes using a small hand-held Doppler ultrasound device.

Continuous electronic monitoring

If you or your baby have any known risk factors, continuous monitoring may be recommended.

This is done using a CTG (cardiotocograph) machine. This type of monitoring is external (outside your abdomen).

Telemetry

Telemetry is a wireless system of monitoring that can be used while you are mobile and walking around, even in the shower.

Fetal scalp electrode (FSE)

Sometimes it is necessary to attach the monitor directly onto your baby via a special lead. This is called a fetal scalp electrode. The lead is placed on your baby’s head during an internal vaginal examination. Telemetry (wireless) monitoring is still available using an FSE.

This type of monitoring is internal and is more reliable and accurate than external monitoring, particularly when you are mobile.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

-

Concerns for baby in labour

When immediate birth is required

If there are concerns for baby’s wellbeing and immediate birth is required, baby will be birthed as soon as possible with vacuum or forceps (or perhaps by caesarean birth).

A change in the baby’s heartbeat can be a sign the baby isn’t getting enough oxygen. This is called ‘fetal distress’.

Signs of fetal distress include:

- a faster, slower or unusual pattern to the baby’s heartbeat

- a bowel movement by the baby seen as a greenish black fluid called ‘meconium’.

If these signs are present, your doctor or midwife will discuss with you, your continued management and care during your labour.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

Why is meconium a concern?

Meconium aspiration syndrome

Meconium aspiration syndrome is when a baby inhales the meconium before, during or after labour.

It can cause respiratory problems as serious as pneumonia, and although it rarely happens, it can be fatal.

Meconium stained fluid occurs with about 10% of babies who are 'term' (37 to 42 weeks).

The presence of meconium during labour can be (but not always) a sign that the baby is becoming distressed.

Your labour will be observed closely and a paediatrician will be available at the birth, in case specialised care is required.

-

Antibiotic treatment during labour

Antibiotic treatment during labour may be recommended for:

- preterm labour – if you are in preterm labour, it may be caused by an infection

- PROM (Prolonged Rupture of Membranes) – to prevent a uterine infection

- Group B Strep infection

- having a fever during labour

- a preventative – in some situations, you may be given antibiotics as a preventative measure against potential infection, an example might be for a caesarean birth.

What is a Group B Strep (GBS) infection?

Approximately 15–25% of women are carriers of Group B Streptococcus, without any symptoms. Usually, you do not know you are a carrier.

It is usually detected by a vaginal swab. GBS can come and go during your pregnancy. If it is present when you give birth, there is a chance your baby can become infected.

If you are known to be GBS positive, and you have additional risk factors (e.g. your waters have broken and are therefore no longer providing a protective barrier for your baby), you will be offered antibiotics to try to prevent an infection in your baby.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy

-

Blood loss after birth

Is it normal to bleed after birth?

Yes, bleeding in the days or weeks after birth (also called lochia) is completely normal and occurs regardless of whether you have a vaginal or caesarean birth.

How much bleeding is considered ‘normal’?

Women’s experiences of bleeding after birth vary considerably. In the first few days after birth, the majority of women experience moderate to heavy bleeding, however some experience minimal bleeding. This early bleeding is usually more red in colour.

Over the next few days to weeks, this bleeding will gradually decrease and will change colour. Women describe their blood loss to be browny-red, pinky-red, pale pink or a creamy colour.

The majority of women will stop bleeding between four and six weeks, however some women experience bleeding for longer than this. It is also common for bleeding to be heavier after breastfeeding.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Abnormal blood loss

How much bleeding is too much?

- if you have a sudden and continued increase in your blood loss

- if the blood suddenly changes in colour to a brighter red

- if you are experiencing heavy blood loss and are feeling dizzy, weak, sweaty, pale, have a fast heartbeat or rapid pulse

- if your vaginal discharge is offensive (smelly) – this may indicate infection.

Every woman is different, however, as a general guide – if it has been more than 24 hours since birth and you are soaking more than one maxi-pad every two hours, you may be bleeding too much. If this is happening - call your doctor, midwife or 13HEALTH (13 43 25 84).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Next section: Induction of labour and augmentation

When complications occur, 23 Mar 2023, [https://oss-uat.clients.squiz.net/health/children/pregnancy/antenatal-information/when-complications-occur]

This document is uncontrolled when printed. Before using the information in this document you should verify the current content on https://oss-uat.clients.squiz.net/health/children/pregnancy/antenatal-information/when-complications-occur.