Your antenatal visits are a great way to learn how your baby is growing and what is happening to your body.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women. More information: COVID-19: information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

During visits:

Your antenatal visits are a great way to learn how your baby is growing and what is happening to your body.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women. More information: COVID-19: information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

During visits:

A normal pregnancy lasts 37–42 weeks.

The average length of pregnancy is 280 days or 40 weeks, from the first day of your last menstrual period.

The medical term for the due date is ‘estimated date of delivery (EDD)’.

Did you know that only about 4% of women give birth on their baby’s due date!

More information: Better Health Channel – Baby due date

At your first appointment with your doctor or midwife, you will plan on who to see and when. Your appointments will generally follow the recommended antenatal schedule, shown in your Pregnancy Health Record.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women.

Ask your doctor or midwife about:

For after your baby is born, ask your doctor or midwife about:

Your doctor, midwife, or obstetrician is usually the best place to start.

Other contacts:

More contacts are listed in your Pregnancy Health Record.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the routine blood tests offered in pregnancy.

These tests are performed to check for anything that may cause problems during pregnancy or after the birth.

Other tests may include a:

More information: Pregnancy Birth and Baby – Blood tests during pregnancy

There are four main blood groups. A, B, AB, and O.

A blood test in early pregnancy tells you which blood group you are, and whether you are Rh positive or Rh negative. Most women (85%) are Rh positive.

If you are Rh negative and your baby is Rh positive it can cause health problems which can be treated.

You will be offered an Anti-D injection at 28 weeks and at 34 weeks of your pregnancy.

You will also be offered an Anti-D injection if you have:

You will also require a blood test following birth and may be given an Anti-D injection within 72 hours of your baby's birth if your baby is Rh positive.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines, Parent Information - RhD negative blood type in pregnancy

Gestational diabetes only develops in pregnancy.

The condition occurs in two to three of every 100 pregnant women.

How do I find out if I have gestational diabetes?

Due to COVID-19, testing for gestational diabetes might be different to what is usually done.

If you have risk factors for gestational diabetes you will be offered a blood test in the first trimester.

All other women will be offered a blood test around 24–28 weeks of pregnancy. You may have to have a second test where you are given a special glucose drink and have blood samples taken over two hours.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss what is best for you.

For more information about gestational diabetes visit:

Antenatal ultrasound scans are recommended at certain points during pregnancy to check the:

We also use scans to monitor:

Learn more about routine tests and your care during pregnancy.

Your doctor or midwife will advise you when an ultrasound may be recommended. The following ultrasounds are common in pregnancy.

An early ultrasound at around 8 to 9 weeks is considered to be the best time to confirm the due date, ensure the pregnancy is in the uterus (womb) or for reassurance.

An ultrasound (also known as a nuchal translucency scan or early structural assessment) is recommended for all pregnant women. If combined with a blood test (free Beta-HCG and PAPP-A), it can be used to generate a risk for chromosomal abnormalities called a combined first trimester screen.

This is a screening test that will calculate your estimated risk of having a baby with Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities. This ultrasound scan also helps to exclude any major structural abnormalities of your baby early in pregnancy and can be used to screen for preterm preeclampsia if this is offered.

If you decide to use a blood test for genetic screening such as NIPT, it’s also very important to check for physical abnormalities of your baby by having this ultrasound.

This is an important ultrasound used to rule out major physical abnormalities in your baby and check the location of the placenta.

It is also important to check the length of your cervix at this scan as a short cervix predicts preterm birth. Most parents know this scan as 'the one where we may find out the baby’s sex'.

You’ll need a referral from a health professional.

You can have your ultrasounds done at a radiology clinic. In some cases, you may be referred to a hospital. Use service finder on the Health Direct website to find your nearest a radiology service.

There may be a charge for your ultrasound depending on where you have it. Some will bulk bill through Medicare. Please talk to a health professional if you can’t pay out of pocket expenses for an ultrasound.

Your body is undergoing many changes during pregnancy and you may experience some health issues along the way.

Many of these issues are a normal part of pregnancy. If you are concerned, talk to your doctor or midwife.

Common discomforts during pregnancy may include:

More information:

You can read these helpful tips for managing morning sickness and find out more information on severe vomiting during pregnancy.

During pregnancy it is important for both you and your baby that you eat well. Your choices of what to eat and drink at this time can affect your health and the health of your baby for many years to come.

There is only a small increase in the amount of food you need to eat while you are pregnant.

However, you do need more of certain nutrients, so it is very important that you make good choices for a nutritious diet.

Folate is needed for the growth and development of your baby. It is especially important in the month before you fall pregnant and the first trimester (three months) of pregnancy.

A good intake of folate reduces the risks of your baby being born with some abnormalities such as spina bifida (a disorder where the baby’s spinal cord does not form properly).

Dietary sources high in folate include:

Women planning a pregnancy and in the early stages of pregnancy should eat a variety of folate-containing foods. You should also take a folic acid supplement of 400 micrograms per day at least one month before, and three months after, you become pregnant.

You need more iron during pregnancy. If you do not have enough iron, you may develop anaemia.

Good sources of iron include:

If you are low in iron, your doctor or midwife may suggest taking an iron supplement (tablet or liquid).

You can help your body get iron from the food you eat or drink by:

Pregnant women need 27 mg iron each day. Pregnant women should not eat more than 45 mg iron each day.

Adequate iodine in pregnancy is essential for your baby’s growth and brain development.

Iodine is important for your baby’s development in the womb.

Good food sources of iodine include:

Pregnant women should take a supplement containing 150 micrograms of iodine each day.

A multivitamin during pregnancy is not necessary unless you do not have a balanced diet. Compare what you are eating with the following food group table.

Remember, a folic acid supplement is important during the first trimester of pregnancy, and iodine is essential during pregnancy (and breastfeeding). You may also need to take an iron supplement if your iron levels are low.

You may choose to get these nutrients from individual tablets or from a multivitamin.

Always check with your doctor or midwife before taking any supplements, as an excessive intake of these can be harmful and reduce the absorption of other nutrients.

More information: Queensland Health Nutritional Education Materials Online (NEMO)

Food group | Serves per day (for 19-50 year olds) | 1 serve equals |

|---|---|---|

Vegetables and legumes/beans | 5 | ½ cup cooked green or orange vegetables (e.g. broccoli, carrot, pumpkin or spinach) ½ cup cooked, dried or canned beans, chickpeas or lentils (no added salt) 1 cup raw leafy green vegetables ½ medium potato, or other starchy vegetable (sweet potato, taro, or cassava) ½ cup sweet corn 75g other vegetables (e.g. 1 small-medium tomato) |

Fruit | 2 | 1 piece medium sized fruit (e.g. apple, banana, orange, pear) 2 pieces smaller fruit (e.g. apricot, kiwi fruit, plums) 1 cup diced, cooked or canned fruit ½ cup 100% juice 30g dried fruit (e.g. 1½ tbsp sultanas, 4 dried apricot halves) |

Grain (cereal) foods - mostly wholegrain | 8½ | 1 slice of bread ½ medium bread roll or flat bread ½ cup cooked rice, pasta, noodles, polenta, quinoa, barley, porridge, buckwheat, semolina, cornmeal ⅔ cup breakfast cereal flakes ¼ cup muesli 3 crisp breads 1 crumpet or 1 small English muffin or scone |

Lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans | 3½ | 65g cooked lean red meats (e.g. beef, lamb, pork, venison or kangaroo) or ½ cup lean mince, 2 small chops, 2 slices roast meat 80g cooked poultry (e.g. chicken, turkey) 100g cooked fish fillet or 1 small can fish, no added salt, not in brine 2 large eggs (120g) 1 cup (170g) cooked dried beans, lentils, chickpeas, split peas, canned beans 170g tofu ⅓ cup (30g) unsalted nuts, seeds or paste, no added salt |

Milk, yogurt, cheese and/or alternatives - mostly reduced fat | 2½ | 1 cup (250ml) milk 40 g (2 slices) hard cheese (e.g. cheddar) 120g ricotta cheese 200g yoghurt |

The weight you should aim to gain will depend on what your body mass index (BMI) was before you became pregnant. Use this tool to calculate your BMI.

Your BMI is the number used to work out your recommended amount of weight gain.

Pre-pregnancy BMI | Recommended total gain | Weekly guide in 2nd and 3rd trimester |

Less than 18.5 kg/m² | 12½ to 18kg | 1/2 kg per week |

18.5 to 24.9 kg/m² | 11½ to 16kg | 400g per week |

25 to 29.9 kg/m² | 7 to 11½ kg | Less than 300g per week |

Above 30 kg/m² | 5 to 9kg | Less than 300g per week |

You may find it easier to follow a pregnancy weight gain chart. The charts are divided in two groups:

More information: How much weight should I gain while pregnant.

Listeria is a bacteria found in some foods, which can cause an infection called listeriosis. If passed on to your unborn baby it can cause premature birth, miscarriage or damage. Throughout your pregnancy, it is important to avoid foods that have a high risk of containing listeria.

Foods that might contain Listeria and should be avoided include:

Fish is a safe and important part of a healthy diet. It is an excellent source of protein, low in saturated fat, high in omega 3 fish oils and a good source of iodine.

However, some types of fish should be restricted as they may contain higher levels of mercury.

Recommendations for pregnant women

(1 serve = 150g)

1 serve per fortnight of shark (flake) or billfish (swordfish/broadbill and marlin) and NO other fish that fortnight

or

1 serve per week of Orange Roughy (Deep Sea Perch) or catfish and NO other fish that week

or

2–3 serves per week of any other fish and seafood not listed above.

Do not eat raw or undercooked eggs. Eggs must be cooked through so that both the white and yolk are hard.

Here are some tips for keeping your food safe:

More information on healthy eating during pregnancy, including fact sheets and resources suitable for Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Maori, and Pacific Islander women are available through Queensland Health Nutritional Education Materials Online (NEMO).

It’s great to be active and stay fit while you’re pregnant.

Check with your doctor or midwife to make sure there are no health problems to prevent you from exercising.

If there are no problems, try to do 30 minutes of moderate exercise (like walking) on most days of the week.

Regular exercise can help you:

Pregnancy can increase your risk of injury because your joints loosen up to let your body grow and make it easier to give birth.

You can prevent injury in pregnancy by avoiding high impact exercise like jumping up and down, repetitive bouncing movements, and any movements that over-stretch your hip, knee, ankle or elbow joints.

Stop exercising if you experience:

Read more information on pregnancy and exercise.

By performing pelvic floor exercises, you can strengthen muscles to help reduce or avoid stress incontinence after pregnancy.

Incontinence is a common but treatable condition – view the video below or visit the Continence Foundation of Australia for more information.

To learn safe exercises, you can download a copy of Pelvic floor health for expectant and new mums from the Continence Foundation of Australia.

This video answers the question about why a woman has an increased risk of leaking urine (urinary incontinence) after childbirth. Find out how to prevent this from happening, how to treat the condition and where to get help.

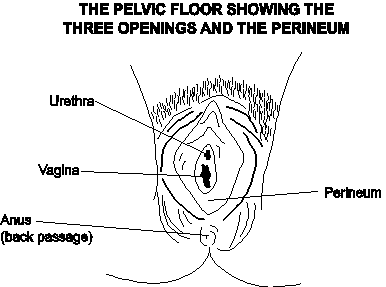

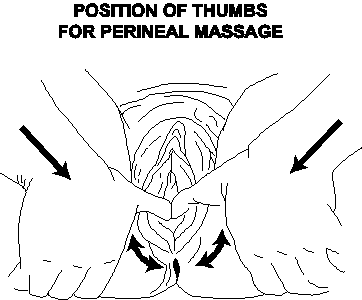

From about 35 weeks you can start preparing for your labour and birth with perineal massage.

Research has shown that massaging the perineum during late pregnancy may encourage elasticity and reduce the risk of tearing during childbirth.

The perineum is the area between the vaginal opening and anus. Some women choose to use perineal massage as a way of (hopefully) reducing their risk of perineal trauma during childbirth.

You can start massage from about 35 weeks and perform no more than three times per fortnight.

Ask your doctor or midwife for more information.

Not all medicines are safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

This includes medicines that are prescribed, natural supplements, or over the counter from the pharmacy or supermarket.

Make sure you tell your doctor or midwife, and pharmacist, about all the medicines you are taking – especially if you:

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines – Using drugs in pregnancy

The safest choice for your baby is to not drink any alcohol.

The risk of damage to your baby increases the more you drink, and binge drinking is especially harmful.

There is no safe amount of alcohol to drink when you’re pregnant.

If you drank small amounts of alcohol before you knew you were pregnant, be reassured that the risk of harm to your baby is low.

More information: The National Organisation for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alcohol and Pregnancy

Stop smoking during pregnancy and you and your baby will immediately feel the benefits.

Toxic chemicals are absorbed into your bloodstream and passed on to your baby through the umbilical cord. If you are unable to stop smoking, cut down as much as you can.

For advice and support visit Quit HQ or call Quitline on 13 78 48.

More information: Pregnancy Birth and Baby - Smoking and pregnancy

When you feel the urge to smoke:

More information: Coping with quitting and staying smoke- and vape-free

Immunisation is a simple and effective way to protect yourself and your baby from certain infections.

During pregnancy, it is recommended that you have the following vaccinations.

Influenza can cause serious illness and being pregnant increases the risk of influenza complications, especially with the H1N1 influenza virus. Influenza vaccine is safe and can be administered before, during or after pregnancy.

Whooping cough can cause serious illness and even death in babies less than six months old. It is now recommended that all pregnant women receive a pertussis (whooping cough) vaccination during their third trimester (ideally at 28 weeks) of every pregnancy.

Check with your doctor whether you have immunity against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox – as well as influenza and whooping cough.

More information:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a new virus and we are still learning how it may affect you and your baby.

To reduce your chance of getting the virus, follow these prevention measures:

Read about the common viral infection cytomegalovirus (CMV).

It is important to wear gloves when gardening and wash hands afterwards.

Cats can be a source of Toxoplasmosis—a serious infection that can cause defects or death in your baby. It is important to avoid contact with cats and use gloves when handling cat litter.

Pregnancy, birth and early parenthood are times of great change.

During pregnancy most women experience a range of emotions. Your pregnancy hormones may make you more emotional than usual. You may worry about whether your baby will be normal and how you will cope with labour. It helps if you can talk openly about any concerns with your partner or a close friend.

Read more about pregnancy and new parents and visit Dear Mind for many ways to strengthen your mental wellbeing.

Depression and anxiety can occur at any time in your life and can often come to the surface with major events like pregnancy or having a baby.

Around 12% of pregnant women in Australia experience antenatal depression (depression during pregnancy). The risk is higher if you have been depressed in the past.

It is important to keep a check on how you are feeling emotionally and discuss any concerns with your health professional. Let someone know if you are:

Read more on perinatal anxiety or find a health professional at Beyond Blue.

Partners share many of the experiences of pregnancy.

Partners also experience the worries, problems, pleasure, and the waiting. Sometimes partners may also have issues of their own to work out.

You can read and share information from Dad’s guide to fatherhood and Dads guide to pregnancy.

There is also information in many languages from the Multicultural Health Communication Service.

If you or someone you know is showing signs of depression or anxiety, there are places you can go to for help.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby Helpline: 1800 882 436

Beyond Blue – Pregnancy and new parents: 1300 224 636

MUMspace – support for the emotional health of new mums, at every step.

Prenatal Anxiety and Depression Australia (PANDA): 1300 726 306

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Mensline Australia: 1300 789 978

Sane Australia Helpline: 1800 18 7263

White Cloud Foundation: 1300 702 926

Depression and anxiety can occur at any time in your life and can often come to the surface with major events like pregnancy or having a baby.

Around 12% of pregnant women in Australia experience antenatal depression (depression during pregnancy). The risk is higher if you have been depressed in the past.

It is important to keep a check on how you are feeling emotionally and discuss any concerns with your health professional. Let someone know if you are:

Read more on perinatal anxiety or find a health professional at Beyond Blue

Partners share many of the experiences of pregnancy.

Partners also experience the worries, problems, pleasure, and the waiting. Sometimes partners may also have issues of their own to work out.

You can read and share information from Dad’s guide to fatherhood and Dads guide to pregnancy.

There is also information in many languages from the Multicultural Health Communication Service.

If you or someone you know is showing signs of depression or anxiety, there are places you can go to for help.

In addition to the natural physical preparation your body makes for birth, you may also find yourself preparing emotionally.

You may:

These concerns are common. Discuss your concerns with your midwife or doctor, so you can feel prepared and informed before labour starts.

Preparation for labour starts during pregnancy.

Your birth preferences (sometimes known as a birth plan) is a written list of what you would like to happen when you are in labour and give birth.

Birth preferences may include:

Remember that things may not go according to plan.

There may be complications, or you may change your mind about something. Think about what is important to you for your birth.

Other questions to consider when deciding on your birth preferences may be:

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby - Making a birth plan

It can be helpful to have people around you who can provide both emotional and physical support during labour.

Hospitals usually allow two support people with you in labour. This could be your partner, another family member or a friend.

Studies show that women who have someone with them right through labour have a more positive experience of labour and are less likely to need medication for pain relief.

Please note: Due to COVID-19, the number of support people you can have with you during labour and birth may be limited. It is suggested that you choose someone who can stay with you for the whole time.

There are many things a birth partner can do to provide support.

They can:

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Being a birth support partner

Your body is getting ready for childbirth throughout your pregnancy, especially in the last few weeks with final preparation.

The pelvis is made up of two large bones joined by cartilage and ligaments – at two joints in the woman's lower back at the sacrum (called the sacroiliac joints) and at the front symphysis pubis bone.

During late pregnancy a hormone softens and relaxes these ligaments. This gives the pelvic bones the ability to stretch and open more easily for the birth of your baby. It is common in late pregnancy to experience lower back pain, or you may notice that you have a ‘pregnancy waddle’ when walking, due to these changes.

Braxton Hicks are also called ‘practice contractions’ because they are preparation for labour.

Braxton Hicks contractions can begin as early as the second trimester. However, they are most commonly experienced in the third trimester. When this happens, the muscles of the uterus tighten for approximately 30 to 60 seconds and sometimes as long as two minutes. If you have concerns or think you might be in labour, contact your midwife or the hospital.

Braxton Hicks are described as:

if your contractions are easing up in any way, they are most likely Braxton Hicks.

Your baby may begin moving lower in the pelvis, which is called engagement.

How will I know if baby’s head is engaged?

You might notice this as increasing pressure in your lower abdomen, or you might notice that breathing becomes easier.

Your baby is designed for the birth process

The baby's skull bones are divided into five plates that cross over during labour, making their head smaller by moulding to fit the birth canal. Mother and baby work together during labour.

There are things you can do during pregnancy to encourage baby into the best position for labour.

How you sit and use your body can affect the position of your baby in the uterus.

While this does not matter so much during early pregnancy, later on it can affect the position that the baby moves into (in the pelvis).

Presentation during labour refers to which part of the baby enters the birth canal first. Normally, the crown of the head will enter first, which is known as cephalic presentation. Other forms of presentation such as breech presentation may cause difficulties with birth.

Once the baby is head down, the best position for a labour is the anterior position.

Anterior position means the baby’s head enters the pelvis facing your back.

This is the ideal and most common position for birth (see image). When baby is in the anterior position, the smallest dimension of the baby’s head leads the way through the birth canal.

You can use different positions during your pregnancy to give you the best chance of ‘optimally positioning your baby’ prior to labour.

Positions include:

Posterior position means the baby’s head enters the pelvis facing your stomach instead of your back.

It’s good to know that most babies will turn around during labour, but some don't.

How can this affect my labour?

If your baby is in the posterior position when labour starts, it can lead to a longer labour with more backache.

If baby doesn’t turn, you may be able to push baby out yourself or your doctor may need to turn the baby’s head and/or help your birth with forceps or a vacuum cup.

Seek advice from your doctor or midwife, or come to hospital if you:

IMPORTANT: Call the hospital any time, day or night, to speak with a midwife. You will be asked questions about what is happening. You can then plan when to come into hospital.

Bring your Pregnancy Health Record with you.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – What happens to your body during childbirth

For mother:

For birth partner:

For mother:

For baby:

Other:

The human pelvis has a complex shape, making your baby negotiate several manoeuvres during labour and birth.

Every mother’s pelvis is widest side to side at the entrance – because of this, most babies enter the pelvis looking left or right. The exit from the pelvis is widest from front to back, so babies almost always turn face up or face down.

These manoeuvres occur from forces of labour and the resistance provided by the birth canal. In addition to making these turning manoeuvres, the baby is simultaneously descending further down the vagina.

Finally, the top of your baby’s head appears (crowns), stretching your vaginal opening. When the vulva has stretched enough, the baby’s head will emerge – usually by extending the head, lifting its chin off the chest and thus emerging from under your pubic bone.

The baby usually emerges face down but will turn to one side very quickly as the shoulders turn to take the same route. The rest of the body is born and then you can hold your new baby!

Oxytocin: Known as the hormone of love, oxytocin is secreted during sex, after ovulation and during labour, birth and breastfeeding. It creates nurturing and loving feelings.

Endorphins: Endorphins are produced in response to pain and stress. Endorphins have calming and pain-relieving effects. As labour progresses and pain intensifies, endorphin levels steadily increase in unmedicated labours.

Adrenaline: Adrenaline is also known as the ‘fight or flight’ hormone. Adrenaline is secreted in response to stress, fear and extreme pain. If a woman experiences these feelings during labour, too much adrenaline may be produced which can slow labour.

More information: Hormones in labour: oxytocin and the others – how they work

Labour is divided into four stages.

The main signs of labour starting are:

The first stage of labour is made up of three different phases and involves the thinning of the cervix and its dilation to around 10 centimetres.

Latent phase

Active phase

Transition

Throughout the first stage of labour, careful monitoring and recording of your wellbeing, your baby’s wellbeing, and the progress of your labour, is important. This helps us to know whether your labour is progressing normally, to recognise any problems early and for clear communication. Ideally, you will experience the latent phase in the comfort of your home. You may wish to come to hospital as you move through the active phase.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Early labour

Birth partner’s role

Helping yourself in first stage

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Giving birth - first stage of labour

The second stage of labour is the birth of your baby.

The second stage of labour starts when your cervix is fully dilated, and you will usually have a strong urge to push because of the pressure your baby’s head is placing on your pelvic area.

At this stage your baby is moving from your uterus into your vagina and out into the world.

The second stage can last from 10 minutes to two hours.

Helping yourself during the second stage

Birth partner’s role

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Giving birth - second stage of labour

After the birth of your baby, your uterus gently contracts to loosen and push out the placenta. This may occur five to 30 minutes after the birth of your baby.

The muscles of the uterus continue to contract to stop the bleeding. This process is always associated with a moderate blood loss – up to 500 millilitres. In this stage of labour, one of the potential problems is excessive bleeding (postpartum haemorrhage), which can result in anaemia and fatigue. This is why the third stage is carefully supervised.

There are two approaches to managing the third stage:

What is a natural third stage?

A physiological or natural third stage means that you wait for the placenta to be delivered naturally.

After your baby's birth, your midwife will delay clamping the umbilical cord to allow oxygenated blood to pulse from the placenta to your baby.

Your uterus (womb) will contract, and the placenta will peel away from the wall of your uterus. The placenta will then drop down into your vagina, ready for you to push it out.

Delayed cord clamping

For baby

The benefits of delayed cord clamping for the baby include a normal, healthy blood volume for the transition to life outside the womb; and a full count of red blood cells, stem cells and immune cells which results in higher iron stores in the baby for up to six months.

For mother

Delayed clamping keeps the mother-baby unit intact and can prevent complications with delivering the placenta.

Benefits of an active third stage

The advantage of an active third stage is the lower risk of very heavy bleeding immediately after the birth. Your midwife or doctor will recommend you have an active third stage if you had complications during pregnancy or labour, such as:

Active third stage

Immediately after the birth of your baby, the midwife or doctor gives you (with your consent) an injection of oxytocin, clamps and cuts the umbilical cord, and then carefully pulls on the cord to speed up delivery of the placenta.

Modified active third stage

This is a combination of active and natural. It is similar to active third stage but it includes delayed cord clamping.

After the birth, you and your partner will be given time with your baby so that you can get to know one another.

While you are holding your baby, your midwife or doctor will do a check called an ‘APGAR score’.

The APGAR score will be done twice, at one minute and five minutes after birth. You probably won’t even notice it’s being done, as the midwife can do this while baby and mother are skin to skin.

It helps the midwife or doctor to know whether your baby needs additional care following birth.

The APGAR score is based on the baby’s:

Blood loss after birth is normal.

Bleeding in the days or weeks after birth (also called lochia) is completely normal and occurs regardless of whether you have a vaginal birth or caesarean birth.

What is normal blood loss after birth?

Women’s experiences of bleeding after birth vary considerably. In the first few days after birth, most women experience moderate to heavy bleeding. Over the first few days to weeks this bleeding will gradually decrease and will change colour.

Most women will stop bleeding between four and six weeks after birth. It is also common for bleeding to be heavier after breastfeeding.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

A normal pregnancy lasts 38–42 weeks.

Every labour and birth is different. It is still not known exactly what happens to start labour.

The average length of pregnancy is 280 days or 40 weeks, from the first day of your last menstrual period. The medical term for the due date is estimated date of delivery (EDD).

Did you know that only about four percent of women give birth on their baby’s due date!

Most women’s waters break during labour, but it can also happen before labour starts.

When your waters break, the amniotic sac breaks, and the fluid drains out through your vagina. It can be a gush or a slow trickle.

The fluid will usually be clear but can be yellow or straw coloured. If it is green or red in colour, there may be a problem.

What should I do when my waters break?

Whatever the colour, you should put a pad on and call your midwife or the hospital who will advise you on when to come into hospital.

All labours are different. Every labour is unique. The length of each person’s labour is different.

How quickly your labour progresses will depend on the baby descending (going down through the pelvis) and the cervix dilating (opening up) with strong, regular contractions.

On average for your first baby, the:

If you have had a baby before, the:

For up to a week before labour starts, you may notice that your body is preparing for labour.

Some women will notice:

Women describe and experience contractions in different ways.

They may feel like:

At first these contractions are short and may be far apart – sometimes as much as 30 minutes apart.

As your labour progresses, they will get longer, stronger and closer together; until they last for about a minute and are coming faster, about every two or three minutes.

From the beginning of one contraction until the next one begins. You can also time how long the contractions last.

The frequency of your contractions

Using a watch or clock, measure the frequency of your contractions by timing them from the beginning of one to the beginning of the next.

True labour will develop into a regular pattern, with your contractions growing closer together. In false labour, contractions remain irregular.

The length of your contractions

Measure the duration of each contraction by timing when it begins and when it stops. True contractions last about 30 seconds at the onset and get progressively longer up to 75 seconds and stronger. False labour contractions vary in length and intensity.

Seek advice or come to hospital if:

Call ‘000’ for an ambulance if:

See ‘Final preparations for labour’.

When you arrive, a midwife will talk about what is happening to you and discuss your birth preferences.

The midwife will:

What can I do if labour is progressing slowly?

It’s good if you can relax and stay calm – anxiety can slow things down.

The midwife may suggest:

Kneeling, on the bed or floor, leaning against a large pile of pillows, or supported by a partner. Some women may feel more comfortable with one knee up.

Squatting, supported by partner behind, or holding onto a bar. The woman should stand to rest between contractions. This may not be appropriate for women who have had epidurals.

Sitting, such as on a toilet or birth stool, with the legs wide apart and leaning forwards with the arms supported on the thighs, or by a partner.

An episiotomy is a surgical cut in the woman’s perineum (area between the vagina and anus) during birth.

You may need an episiotomy (with your consent) when for some reason, related to your baby or you, your doctor or midwife believes there is a chance that your perineum may tear when the baby’s head comes through during the second stage of labour. This is more likely to occur when forceps or a vacuum assistance is required.

Research has shown that the selective use of episiotomy may reduce a more severe vaginal or perineal tear.

During labour, your baby's heart rate will be checked regularly.

If you have had a healthy pregnancy and there are no problems at the onset of labour, your baby's heart will be listened to every 15 to 30 minutes using a small hand-held Doppler ultrasound device. This equipment can be used regardless of the position you are in, even in the shower.

If you had problems during pregnancy or if problems arise during your labour, your baby’s heart rate may be monitored continuously using a cardiotocograph (CTG).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

A CTG (cardiotocograph) involves having two plastic disks (receivers) strapped to your abdomen and held in place by two belts. The receivers are attached to a machine, which may limit your movement. Some machines are wireless, enabling you to move around freely while you are being monitored. This is known as telemetry.

What happens during a vaginal examination?

When a woman's cervix thins during labour it is referred to as effacing. When her cervix is opening it is called dilating.

These cervical changes can be measured by the caregiver doing a vaginal examination with their gloved fingers during labour, often referred to as a VE.

During labour, vaginal examinations are usually carried out after a contraction finishes and when the woman says she is ready.

Request to take the placenta home

The birth placenta holds significant value in some cultures and for some people. It is not uncommon for people to bring their baby’s placenta home, bury it in the garden and plant a tree above it.

You have the right to take your placenta home – speak to your midwife about the policy and how the hospital will support you.

After baby is born, you will be given a birth registration pack.

Information includes:

In the case of same sex female parents, only one parent can be registered as the baby's mother.

More information:

Every woman is different. Every labour is different.

Sometimes pregnancy, labour and birth may not go as planned. The reasons are usually complex.

This module will discuss the following important topics:

Always talk to your doctor or midwife if you are concerned.

Symptoms of pre-eclampsia may include:

What is pre-eclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia is a serious disorder of pregnancy characterised by high blood pressure and serious complications of other organs in the body. Without treatment, seizures can develop. This can be fatal for mother and baby.

It is the most serious medical complication of pregnancy, affecting around five to 10% of all pregnancies in Australia. Researchers still do not know exactly why it happens in some pregnancies.

Regular antenatal checks are vital to keep a check on your blood pressure. Sometimes medication is needed. The onset of pre-eclampsia can be fast! If you experience any of the symptoms, seek medical assistance urgently.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Pre-eclampsia

What is a preterm (premature) birth?

A preterm birth is one that happens before 37 weeks of pregnancy. In about half of all preterm births, the cause is unknown.

Factors that increase the likelihood of a premature birth can be:

If babies are premature, they are likely to need extra care at birth.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Preterm labour and birth

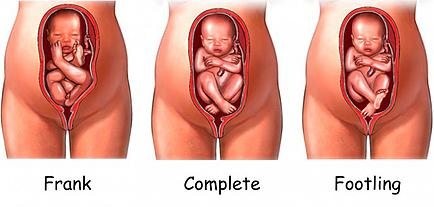

A breech position means the baby presents bottom or feet first, rather than head first.

During pregnancy, many babies are in the breech position. However, most babies turn before 37 weeks.

If your baby is still breech at 37 weeks, the chances of your baby turning by itself are low.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the implications of this for your birth plan and what options are available.

Your options may include:

You may be suitable for a vaginal breech birth if:

More information: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Breech presentation at the end of your pregnancy

ECV is a commonly practiced procedure with a low risk of complications.

ECV can reduce the need for a caesarean birth. The success rate is approximately 40% for first time mothers and 60% for others. If you choose to have an ECV, the procedure is done in hospital.

What you need to know

Mother and baby are monitored during the procedure.

There’s a small risk that turning the baby may tangle the cord or separate the placenta from the uterus – in which case an emergency caesarean birth is needed. If the baby is still in the breech position at the end of pregnancy, a caesarean birth may be recommended.

More information:

Note: treat ‘home remedies’ with a dose of caution.

A simple internet search will give you countless results for ‘natural’ ways to trigger labour. Be sure to get your midwife or doctor’s OK before trying any home remedies, herbal supplements or alternative treatments.

Around 80% of babies are born between 38 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. This is often called ‘at term’. Babies born after 40 weeks are described as ‘post term’.

It's OK to feel frustrated or disappointed if your pregnancy has gone past its due date. Try not to worry, soon you'll hold your baby in your arms and the long wait will be over.

While you are waiting, stay in touch with your midwife or doctor. You'll need frequent check-ups until your baby is born.

Take advantage of the extra time. You may want to:

If your labour hasn’t started by 41 weeks, your midwife or doctor will probably offer you a 'membrane sweep’.

What is a membrane sweep?

A membrane sweep involves a vaginal (internal) examination that stimulates the cervix (neck of your womb) to produce hormones that may trigger natural labour.

If your labour still doesn’t start naturally after this, your midwife or doctor will discuss with you a date to have your labour induced.

If your pregnancy lasts longer than 42 weeks there is a higher risk of complications.

Your doctor or midwife will probably recommend regular tests to check on your health and your baby’s health. After 42 weeks, there is a higher risk of stillbirth or fetal compromise.

These tests might include an ultrasound to check the amniotic fluid index and an ultrasound to check the biophysical profile.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Overdue

If you have had a healthy pregnancy and there are no problems at the onset of labour, your midwife will listen to your baby's heart beat every 15 to 30 minutes using a small hand-held Doppler ultrasound device.

If you or your baby have any known risk factors, continuous monitoring may be recommended.

This is done using a CTG (cardiotocograph) machine. This type of monitoring is external (outside your abdomen).

Telemetry is a wireless system of monitoring that can be used while you are mobile and walking around, even in the shower.

Sometimes it is necessary to attach the monitor directly onto your baby via a special lead. This is called a fetal scalp electrode. The lead is placed on your baby’s head during an internal vaginal examination. Telemetry (wireless) monitoring is still available using an FSE.

This type of monitoring is internal and is more reliable and accurate than external monitoring, particularly when you are mobile.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

When immediate birth is required

If there are concerns for baby’s wellbeing and immediate birth is required, baby will be birthed as soon as possible with vacuum or forceps (or perhaps by caesarean birth).

A change in the baby’s heartbeat can be a sign the baby isn’t getting enough oxygen. This is called ‘fetal distress’.

Signs of fetal distress include:

If these signs are present, your doctor or midwife will discuss with you, your continued management and care during your labour.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

Meconium aspiration syndrome

Meconium aspiration syndrome is when a baby inhales the meconium before, during or after labour.

It can cause respiratory problems as serious as pneumonia, and although it rarely happens, it can be fatal.

Meconium stained fluid occurs with about 10% of babies who are 'term' (37 to 42 weeks).

The presence of meconium during labour can be (but not always) a sign that the baby is becoming distressed.

Your labour will be observed closely and a paediatrician will be available at the birth, in case specialised care is required.

Antibiotic treatment during labour may be recommended for:

Approximately 15–25% of women are carriers of Group B Streptococcus, without any symptoms. Usually, you do not know you are a carrier.

It is usually detected by a vaginal swab. GBS can come and go during your pregnancy. If it is present when you give birth, there is a chance your baby can become infected.

If you are known to be GBS positive, and you have additional risk factors (e.g. your waters have broken and are therefore no longer providing a protective barrier for your baby), you will be offered antibiotics to try to prevent an infection in your baby.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy

Is it normal to bleed after birth?

Yes, bleeding in the days or weeks after birth (also called lochia) is completely normal and occurs regardless of whether you have a vaginal or caesarean birth.

How much bleeding is considered ‘normal’?

Women’s experiences of bleeding after birth vary considerably. In the first few days after birth, the majority of women experience moderate to heavy bleeding, however some experience minimal bleeding. This early bleeding is usually more red in colour.

Over the next few days to weeks, this bleeding will gradually decrease and will change colour. Women describe their blood loss to be browny-red, pinky-red, pale pink or a creamy colour.

The majority of women will stop bleeding between four and six weeks, however some women experience bleeding for longer than this. It is also common for bleeding to be heavier after breastfeeding.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

How much bleeding is too much?

Every woman is different, however, as a general guide – if it has been more than 24 hours since birth and you are soaking more than one maxi-pad every two hours, you may be bleeding too much. If this is happening - call your doctor, midwife or 13HEALTH (13 43 25 84).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Induction of labour (IOL) is a relatively common procedure.

The IOL rate in Queensland is about 22%.

IOL is a procedure used to stimulate contractions, before labour begins on its own. It includes the use of medication or other methods to bring on (induce) labour.

The reasons that an induction could be recommended include:

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the reason for your induction at your antenatal visit.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

It is a score used by doctors and midwives to determine how ‘ready’ your cervix is for labour. It is a combination of how soft, open and thin your cervix is, and where your baby is positioned in your pelvis. The score assists in deciding which method of induction will be most successful for you.

Ripening the cervix is a process that helps the cervix soften and thin out in preparation for labour. Medications or devices may be used to soften the cervix so it will stretch (dilate) for labour.

The method of induction will depend on:

There are lots of factors involved. Some women go into labour and deliver within a few hours after induction. Others take one or two days to start labour.

Your midwife or doctor should discuss the pros and cons of any intervention so you can make an informed decision.

You should ask your doctor or midwife whether induction will:

You should also ask questions such as:

More information:

A cervical ripening balloon catheter

This is a thin tube or catheter with balloons on the end. The catheter is inserted into your cervix and the balloons are inflated with saline (salty water).

Once inflated, the balloons apply pressure to the cervix. The pressure should soften and open your cervix.

What happens next will vary for each woman – some might need an Artificial Rupture of Membranes (ARM) to break their waters. Some women might need oxytocin to stimulate the contractions.

What do I need to know?

When the catheter is in place, you will need to stay in hospital, but you can move around normally. At about fifteen hours after the catheter has been inserted or when it falls out, you will be re-examined (vaginal examination).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

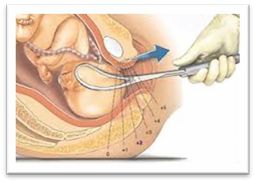

What is a prostaglandin induction?

Prostaglandin is a hormone that prepares your body for labour. A synthetic version of this hormone is inserted into your vagina, behind your cervix, using a syringe (see image).

When the prostaglandin takes effect, your cervix will soften and open.

What do I need to know?

A ‘gel’ induction can be a lengthy process, sometimes one to two days. If the process is started in the evening, you will need to rest while the gel is working. Your support person is advised to go home as there are no facilities to accommodate them overnight.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

What is Cervidil induction?

Cervidil is a tape that contains prostaglandin which is used to ripen (soften), shorten and open the cervix.

A vaginal examination is performed to assess the cervix and the tape is inserted behind the cervix.

What do I need to know?

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

What is a Syntocinon induction?

Oxytocin is the hormone that causes contractions. A synthetic version (Syntocinon) can be given to start the induction process.

Syntocinon is given through a drip, usually in your hand or arm. Once contractions begin, the rate of the drip is adjusted so that contractions occur regularly until your baby is born.

This process can take several hours.

Your baby's heart rate will be monitored throughout labour using a CTG machine.

What do I need to know?

the Syntocinon drip is only an option after your waters have broken.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

A labour that's progressing slowly can be augmented, which means certain techniques are used to speed it along.

If your cervix is opening slowly, or the contractions have slowed down or stopped, your midwife or doctor may suggest medications or techniques to speed up labour. This is known as augmentation of labour.

Methods include:

It is important to note that both induction of labour and augmentation require extra fetal monitoring.

What else can I do if my labour is progressing slowly?

Your midwife may suggest changing your position, walking around, taking a warm shower or bath, or having a massage to encourage the contractions. If you’re tired or uncomfortable, you may want to ask about options for pain relief.

When are medical interventions needed?

A normal, problem-free labour is every pregnant woman's wish, however medical interventions are sometimes needed to help with the birth of a baby.

Some interventions include:

Possible reasons for an assisted birth

Assisted vaginal birth accounts for around 11% of births in Australia. Reasons include:

For baby

For mother

Vacuum birth

This is the more common technique used for assisted deliveries. The vacuum cup is made of plastic and is attached to a suction device. A doctor inserts the cup into the vagina and creates a vacuum against the baby’s head. This helps the doctor to gently pull the baby out as you push.

What do I need to know?

More information: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Assisted birth

A doctor applies forceps, an instrument shaped like a pair of large spoons or ‘salad tongs’, to the baby's head to help guide the baby out of the birth canal. This is done during a contraction while you push.

Forceps birth and baby

What do I need to know?

Your baby may experience:

Serious baby injuries after a forceps birth are rare but could include:

More information:

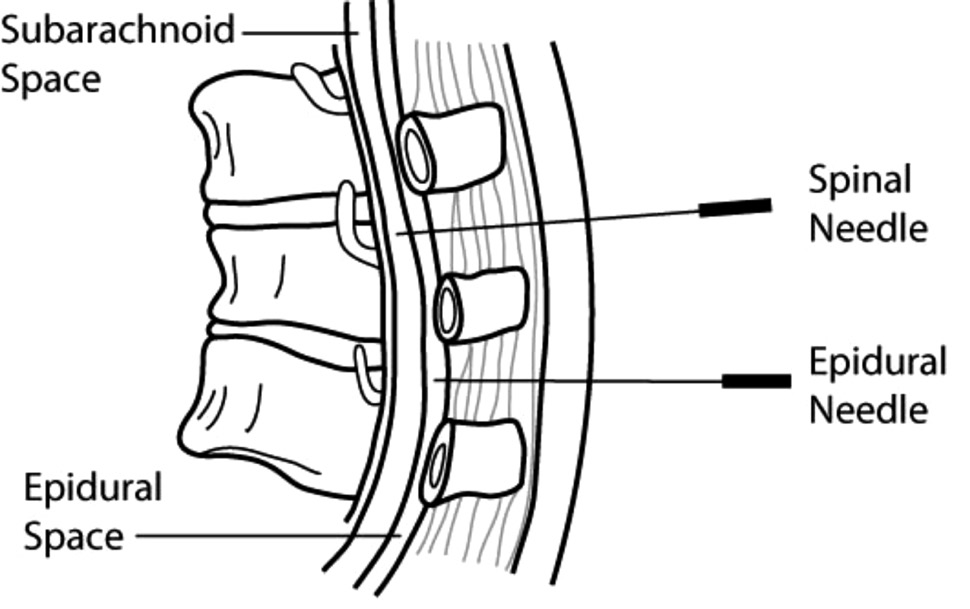

Around one in four Australian babies is birthed by caesarean section. A caesarean section is usually performed under regional (spinal or epidural) anaesthesia. However, sometimes general anaesthesia is required.

A caesarean section is a major surgical operation in which your baby is born through a cut in your abdomen and uterus.

Elective caesarean births are planned in advance because of existing problems with your pregnancy, or if you have had a previous caesarean.

Emergency caesarean births - usually the decision to perform an emergency caesarean is made during the course of labour. An emergency caesarean birth is recommended for the following reasons:

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Caesarean

A planned or elective caesarean birth is required when there is a medical need for the operation. Medical reasons for having a planned caesarean birth include, but are not limited to:

More information:

In an emergency, there may not be enough time to discuss the options of a caesarean birth. If vaginal birth poses significant risks to you or your baby’s health, a caesarean birth may be the safest option.

Reasons for needing an emergency caesarean birth include:

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Emergency caesarean

Before your surgery (if elective):

On the day of your surgery (elective or emergency):

After your caesarean birth

How long will I be in hospital?

After your caesarean birth, you will stay in hospital for about three to five days.

A caesarean birth is major surgery, so your physical recovery is important. This is also a great time to get to know your new baby, with the support of hospital midwives and doctors.

Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) is possible. After a previous caesarean birth, around 60–80% of women who attempt labour will have a vaginal birth.

More information:

Complications of a caesarean birth are rare but can include:

More information: Queensland Government – Caesarean Section Consent form

Understanding the choices of pain relief are an important part of getting ready for the birth of your baby.

Although having a baby is a natural process, it can cause significant pain and discomfort.

Every woman is different, and every birth experience is unique, so the need for pain relief varies.

During labour, your need for pain relief may change, so it’s important that you are open to learning about different ways to manage pain during labour.

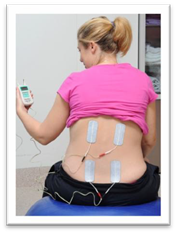

Using a TENS machine in labour

How do TENS machines help during labour pain?

TENS is believed to work by stimulating the body to produce more of its own natural painkillers, called endorphins.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – TENS (Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation)

How are SWIs given?

How can SWIs help during labour?

During labour, SWIs provide effective pain relief for up to 85% of women with back pain and can last for up to two hours.

SWIs have a number of advantages, they:

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Non-medical pain relief during labour

How do I use nitrous oxide in labour?

What is nitrous oxide?

Nitrous oxide is a gas that is mixed with oxygen and administered through a face mask or a mouthpiece held in the mouth.

Nitrous oxide is simple and quick to act and wears off in minutes. It will not take the pain away completely, but it may help.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Gas (Entonox)

What are morphine injections?

Morphine is a strong pain reliever, usually injected directly your arm or thigh.

What are the possible side effects?

For mother:

For baby:

Why are epidurals used during labour and birth?

Epidurals are used for vaginal and caesarean births, because they allow the mother to stay awake and alert during the baby’s birth.

What are the advantages of an epidural?

More information:

Epidural is a local anaesthetic, which is injected into your back (not the spinal cord).

An anaesthetist will put the epidural in. This usually takes about 20 minutes.

An epidural causes muscle weakness in the legs, so women who have had an epidural in labour are confined to bed.

This also means:

Will an epidural hurt?

The answer depends on who you ask. Some women describe an epidural placement as creating a bit of discomfort in the area where the back was numbed, and a feeling of pressure as the small tube or catheter was placed.

When might an epidural not be recommended for pain relief?

There are certain situations where an epidural would not be recommended. For example, medical complications, bleeding disorders, infections, history of back surgery.

Discuss any concerns you may have with your midwife or doctor who will make a referral for you to speak to an anaesthetist prior to your birth.

When can I have an epidural?

Typically, epidurals are placed when the cervix is dilated to 4–5 centimetres or more and you are in true active labour. The timing is determined by your unique experience in labour. You will need to discuss this with your midwife or doctor at the time.

Can an epidural slow down my labour?

Yes. An epidural can cause your labour to slow down and make your contractions weaker. If this occurs, you may be given intravenous oxytocin to help speed up labour. The second stage of labour can be prolonged and assisted birth may be required in certain situations.

Can an epidural affect my baby?

Research shows that epidurals do not directly affect your baby. The drugs used in epidurals do cross the placenta but are considered safe and have minimal effect on baby.

Epidurals have been routinely used for many years and are widely accepted as an effective method of pain relief after surgery, during labour and childbirth. However, as with many medical procedures, there are some associated risks that, although small, you should be aware of before deciding whether to have an epidural.

Risks and benefits of epidurals: Queensland Government – Epidural pain relief for your labour

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Epidural

Perfect food

Breastfeeding is the natural, biological way of providing babies with nutrients required for healthy growth and development.

Better for mum, better for baby

Breastfeeding helps with mother and baby emotional attachment and is better for both short and long term health.

Environmentally friendly

Breast milk has no waste products, so it is better for the environment.

For mothers

Higher risk of:

More expensive:

For babies

Higher risk of:

For the community

Babies know when they are hungry and thirsty. Babies know when the milk comes in. Babies know how to breastfeed.

Allowing babies to do what they were born to do, will make for a much smoother transition into this new world; for mother and baby.

More information:

The World Health Organization and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recommend you breastfeed your baby exclusively for the first six months. Breast milk is all the food and drink that a baby needs.

The Australian Dietary Guidelines (NHMRC) recommends:

The Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) was developed by the World Health Organisation and UNICEF in 1991. It is a worldwide program aiming to create a healthcare environment that supports mothers and babies to have the best start in life.

Queensland Health is proud to support the BFHI. We promote breastfeeding as the optimal way to feed your baby; however we also respect how you choose to feed your baby.

Think about what is important for you.

It is never too early to read, learn and talk about breastfeeding.

Most people have a view about breastfeeding before having their baby. What have you heard from friends, television, or in the community?

Learning about the changes in your breasts during pregnancy may give you a better understanding of your body’s ability to breastfeed. The good news is, no physical preparation is required!

Most women notice breast changes in pregnancy, however some do not. Your breasts will usually increase in size – as the due date approaches, hormone changes cause your breasts to feel larger and tender. Sometimes, visible veins appear. In the third trimester, some pregnant women begin to leak colostrum from their breasts.

Your breasts are filled with milk making glands that are called alveoli. This is where your milk is produced. The milk travels from the alveoli through a series of milk ducts to the nipple openings.

The more often your baby breastfeeds, the more milk your breasts make.

When your baby breastfeeds, your brain releases two hormones.

Prolactin is the hormone that causes your breasts to make milk.

Oxytocin helps with your letdown reflex (release of milk). These hormones also increase the level of bonding and comfort you feel during breastfeeding.

When your baby latches on and begins to breastfeed, the alveoli release milk. This is called the let down or milk ejection reflex. Let down occurs several times during a feed. In the early days, you may not even notice this is happening.

How can I tell if my milk is letting down?

More information: Australian Breastfeeding Association – Breastfeeding Information

Most women can breastfeed with the right information, support and practice.

Speak to your midwife, doctor or lactation consultant if any of the following applies to you:

More information: Australian Breastfeeding Association

Most babies will attach to the breast for their first feed if placed skin to skin (in contact) with their mother.

Skin to skin contact

This is when your baby is placed directly from birth onto your chest or abdomen. Your newborn’s skin touches your skin. A blanket or towel can be placed over the baby’s back for warmth if required. Providing baby and you are well, skin to skin contact should continue, undisturbed, until the first breastfeed. Routine procedures such as bathing and weighing can wait.

If you can’t have skin to skin right after the birth, this is often due to medical reasons.

Your midwife will support skin to skin contact as soon as possible.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Breastfeeding your baby

Most healthy babies will want to feed within the first 90 minutes after birth.

During skin to skin contact, your baby will show feeding signs (cues).

When this happens, position baby close to your breast.

After your baby is born, you will both be in the same room – you will be able to see signs that your baby is hungry, uncomfortable or needs to be cuddled.

Benefits of rooming in:

Newborn feeding behaviour

Birth to two hours

Baby is usually awake and alert (best time to feed).

The first 24 hours

Two to 20 hours after birth, baby will have light and deep sleep (may not want to feed often).

After 20 hours

Baby will have sleep and awake behaviour (and may want to feed often).

Day two to three

Your baby may seem unsettled on day two or three while your colostrum changes to mature milk. Increased breastfeeding is often all that is needed.

More information: NHS – Breastfeeding: the first few days

Mothers can follow their baby's lead in how often to breastfeed.

Rather than watching the clock, watch for cues that your baby is hungry such as the rooting reflex, chewing/sucking on hands or fingers.

Early feeding cues (signs) are the best time to feed!

Early cues: “I’m hungry” (stirring, mouth opening, turning head and seeking/rooting).

Mid-cues: “I’m really hungry” (stretching, increasing physical movement, hand to mouth).

Late cues: “Calm me, then feed me” (crying, agitated body movements, colour turning red).

The first milk is called colostrum. This special milk is yellow in colour, thick and sticky. It may be low in volume but it is high in concentrated nutrition for your newborn.

Colostrum has a laxative effect on baby, helping him or her pass the early stools and helping to prevent jaundice.

The more you feed your baby, the more milk you will make (supply = demand).

Days after birth | Type of milk | How it looks |

Birth to day 2 or 3 | Colostrum | Thick, yellow in colour, small amount |

Days 3 to 5 | Transitional milk | Mixture of colostrum and mature milk more plentiful |

Days 5 to 7 | Mature milk begins | Thinner, whitish, plentiful |

You may find that your breasts become larger and feel heavy, warmer and uncomfortable when your milk ‘comes in’; usually about two to four days after your baby is born.

Your milk will then increase in volume and will generally begin to appear thinner and whiter in colour.

Whenever baby is hungry!

Healthy, full-term newborns should breastfeed eight to 12 times in each 24 hour period. Many mothers are surprised at how quickly and easily human milk is digested, often within 90 minutes of the last feed.

Many babies do what is called 'cluster feeding’, spacing feeds closer together at certain times of the day (usually during the evening). This is normal. As babies grow and their stomachs become larger, they begin to go longer between feeds and develop more regular feeding patterns.

Your baby will determine this.

A typical feed might last about 20–30 minutes. In the beginning, it could take up to an hour.

It is important that you allow the baby to feed for as long as the baby wants on one side.

Do not time the feed or swap sides unless the baby seems to have finished one side. This will ensure that your baby feeds well and helps with your breast milk supply.

If the baby takes only one breast, remember to offer the other breast at the next feed.

When your baby has had enough, they will stop sucking and come off the breast or simply fall asleep. If you notice that baby's jaw isn't moving anymore, you can detach baby. Your breasts keep making milk.

Remember, supply = demand.

A common concern to breastfeeding mothers is how to tell whether their baby is getting enough milk.

Your baby will tell you by:

Seek advice from a healthcare professional if you have concerns.

Age | Feeds per day | Wet nappies | Dirty nappies |

Day 1 | 3–8 | 1 | 1 Black, tarry and sticky |

Day 2 | 5–10 | 2–3, may contain urates. What are urates? Crystals present in strong urine that stain a nappy reddish-orange. | 1–2 Greenish–black, softening |

Day 3 | 5–10 | 3–4 paler, but may be concentrated and contain urates. | 3–4 Greenish–yellow, soft |

Day 4 | 5–-10 | 4–6 pale, no urates. | 4 large or 10 small Yellow and/or seedy, soft/liquid |

Day 5 | 8–12 | More than 6 pale nappies. | 4 large or 10 small Yellow and/or seedy, soft/liquid |

The key to successful breastfeeding is comfortable positioning and good attachment.

Make sure your baby is well attached to the breast. If your baby is only attached to the nipple, breastfeeding will be painful.

If your baby is well-attached to your breast, you are less likely to experience breastfeeding problems like cracked nipples, and your baby will get the most amount of milk from your breast.

Find a comfortable place where you can sit and relax. Have everything you might need close to hand – e.g. phone, glass of water. Breastfeeding may take some time.

This webpage is currently being reviewed and some outdated content has been removed. Please refer to Raising Children Breastfeeding videos and Raising Children Breastfeeding positions in pictures in the interim.

Some tips which may help:

More information: Raising Children Network – Breastfeeding positions: in pictures

Video: Raising Children Network – Breastfeeding: getting a good attachment

Your baby is not attached if:

Avoid pulling your baby away from your breast. Instead, break the attachment by inserting your little finger into the corner of your baby’s mouth, between the gums, and gently remove your baby from the breast.

Front hold or cradle

Underarm or football hold

Side lying

Video: Raising Children Network – How to breastfeed: breastfeeding positions

More information: Australian Breastfeeding Association – Attachment to the breast

Why is my baby’s skin yellow?

Jaundice in the first week of life occurs in 60% of healthy newborn infants. It typically occurs between day two to four after birth and is usually cleared by the first week.

Frequent feeding is the best prevention. If a baby appears to be jaundiced, a blood test can determine the level of bilirubin. Treatment, if any, will depend on the level of bilirubin, how the baby is feeding and how old the baby is. Jaundice appears first on the face and head. If the level of bilirubin goes higher, it will appear on the body, and if it goes even higher it will be on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Jaundice in newborn babies

If you’re breastfeeding, it’s a good idea to avoid using a dummy until breastfeeding is established. This is usually when your baby is four to six weeks old.

Using a dummy (also known as a pacifier) when you plan to breastfeed can:

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Breastfeeding your baby

Partners of new mothers play an important role, they can:

More information:

Video: ACT Government Health – Breastfeeding Give it a Go

Healthy eating is important when you are breastfeeding.

Your body has a greater need for most nutrients; to meet these needs it is important to eat a healthy, well-balanced diet based on a range of healthy foods and plenty of water.

More information: Queensland Health – Nutrition Education Materials Online (NEMO)

Smoking is not recommended while breastfeeding.

Smoking can affect the nutrient content of breastmilk and reduce supply. It also increases the risk of SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome).

Avoid exposing baby to tobacco smoke. Don't let anyone smoke near your baby – whether in the house, car or anywhere else your baby spends time.

For advice and support visit QUIT HQ or call Quitline on 13 78 48.

Alcohol

The safest option is to avoid drinking alcohol while breastfeeding.

Caffeine

Breastfeeding mothers can safely consume caffeine, but they should consume less caffeine than non-breastfeeding women, to protect their health and the health of their breastfed baby.

If you have an existing medical condition or are taking an over-the-counter or prescribed medication, discuss this with your health professional.

Always discuss alternative/natural and complementary therapies, as they may not be safe during breastfeeding.

Always check with your doctor or pharmacist regarding prescription and over-the-counter medications when you are breastfeeding.

More information: Australian Breastfeeding Association – Common concerns - baby

Many women experience some difficulties when establishing breastfeeding.

Most are minor and can be overcome by advice, assistance and support.

Your midwife or a lactation consultant will be happy to help.

For advice contact:

About three days after having a baby, many mothers will experience breast fullness as their milk 'comes in'. Occasionally a mother may need to express a small amount of milk to soften the breast before a feed. This fullness usually only lasts for 24 hours and is different to engorgement.

When it comes to breastfeeding, remember that supply equals demand. The more you feed your baby, the more milk your breasts will make.

Ways to increase or maintain a good milk supply include:

Nipples can be sensitive in the beginning, but breastfeeding should not be painful through a whole feed or continue to be painful.

Helpful hints to avoid sore nipples:

Cracked/bleeding nipples:

If your nipples are cracked or bleeding it is recommended that you seek help from a health care provider.

Mastitis is an inflammation and/or infection of the breast tissue.

Mastitis can be caused by:

Signs of mastitis

Management of mastitis

More information:

Practical support

Involve your family and friends who can provide a network of help with babysitting, social activities and ‘time out’ for you.

Personal support

Talk to friends, family and support groups about how you are feeling.

Information support

Seek information from health professionals, books, websites etc. It can be challenging for you to identify what information is based on the latest recommendations, so be wary of the source of information.

The return of the menstrual cycle is different for every woman.

Even if you are exclusively breastfeeding, you can start ovulating. That means you can get pregnant again without even knowing that it has happened.

Ask your healthcare professional about your family planning options and if they are compatible with breastfeeding.

The Australian Breastfeeding Association has useful information on breastfeeding and work.

Crying is an important means of communication for young babies. Babies always cry for a reason. These include:

Parenting and adjusting to a new baby is rewarding, but it can also bring significant changes and challenges.

If you or your partner are struggling to cope, there is help available. Call and talk to a relative, friend or visit your Child Health Centre, GP, or health professional.

More information:

Most baby’s wake and feed at night until about six months of age.

There is a large variation of what is ‘normal’. Prolactin (milk making hormone) levels are highest at night, so night feeds are important to ensure adequate stimulation and milk removal from the breast.

Night feeds are important because they:

More information:

Almost all mothers in Australia (98%) express milk at some time for their baby in the first six months.

It is important you know how to express milk by the time you are discharged from hospital.

Reasons why some mothers will have to express:

There are three methods of expressing breastmilk:

Whichever way you are expressing, it is important that milk 'lets-down' so that a good quantity of milk is obtained.

Ways to encourage your let-down reflex:

Wash hands with soap and warm water and thoroughly dry. Hold a clean plastic cup/dish under the breast to collect the milk.

1. Gently massage the breast – start from the top of the breast and stroke towards the nipple, massage the underside and repeat several times to ensure that the whole breast is massaged.

1

2. Place thumb and finger diagonally opposite each other on the edge of the areola. Gently press inward towards the centre of the breast, squeezing the finger and thumb together.

2

3. & 4. Repeat with a rhythmic rolling movement, feeling for the milk sinuses – the fingers should not slide over or pinch the skin. Once the milk flow has stopped, move the fingers around the nipple and press again. Repeat the process on the other breast.

3

4

Milk ejection (let down)

Look in your baby’s Personal health record (red book) for more information.

Thawing and warming of breast milk

| Breast milk | Room temperature | Refrigerator | Freezer |

|---|---|---|---|

Freshly expressed into a clean container | 6–8 hours (26°C or lower) | 3–5 days (4°C or lower) |

|

Previously frozen, thawed in a fridge | 4 hours or less | 24 hours | Do not refreeze |

| Previously frozen, thawed outside a fridge in warm water | Completion of feed | 4 hours until next feed | Do not refreeze |

| Baby has begun feeding | Completion of feed | Discard | Discard |

Caution!

In the postnatal ward, your baby will be in the same room so you can see signs that your baby is hungry, uncomfortable, needs a change or wants a cuddle. We call this ‘rooming in’.

There are many benefits to rooming in:

Sharing your bed with your baby for the purpose of sleeping is not an accepted practice within the hospital environment, as in some circumstances this has been associated with an increased risk of sudden infant death (SIDS) and fatal sleeping accidents.

Please return your baby to the cot after feeding and cuddles. This is especially important when you are very tired and finding it difficult to stay awake.

More information: Red Nose – safe sleeping

Your baby needs to have two identification bands (usually one on their hand and foot) and a tape identification on their back at all times. Please notify your midwife/nurse immediately if any of these become loose or fall off.

If you are ever separated from your baby, ensure that you and the staff check the identification bands against yours, once you are reunited.