Antenatal information Guide

Your antenatal visits are a great way to learn how your baby is growing and what is happening to your body.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women. More information: COVID-19: information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

During visits:

- your blood pressure will be checked

- the doctor or midwife will palpate (feel) your abdomen to see how much your baby has grown and listen to your baby’s heartbeat

- sometimes you may be weighed, have blood taken for tests and may have your urine checked.

-

Your care during pregnancy

-

Antenatal visits

Your antenatal visits are a great way to learn how your baby is growing and what is happening to your body.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women. More information: COVID-19: information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

During visits:

- your blood pressure will be checked

- the doctor or midwife will palpate (feel) your abdomen to see how much your baby has grown and listen to your baby’s heartbeat

- sometimes you may be weighed, have blood taken for tests and may have your urine checked.

Your due date

A normal pregnancy lasts 37–42 weeks.

The average length of pregnancy is 280 days or 40 weeks, from the first day of your last menstrual period.

The medical term for the due date is ‘estimated date of delivery (EDD)’.

Did you know that only about 4% of women give birth on their baby’s due date!

More information: Better Health Channel – Baby due date

When do I see my doctor or midwife?

At your first appointment with your doctor or midwife, you will plan on who to see and when. Your appointments will generally follow the recommended antenatal schedule, shown in your Pregnancy Health Record.

Due to COVID-19, prenatal visits might be different. Some doctors and midwives are using telehealth to see pregnant women.

Things to ask at your visits

Ask your doctor or midwife about:

- results of tests and investigations

- smoking, alcohol and drug use

- managing back or pelvic pain

- premature labour - what to look out for

- who and when to call when you’re in labour

- labour and birth - what to expect and making a birth plan

- planning for your hospital stay and going home with your baby.

For after your baby is born, ask your doctor or midwife about:

- tests for your baby – including the Healthy Hearing and Neonatal Screening Tests

- Vitamin K injection for newborns

- immunisations for yourself and your baby

- breastfeeding

- the importance of ‘rooming in’

- skin to skin contact

- where to get help with breastfeeding.

Who can I call to ask questions?

Your doctor, midwife, or obstetrician is usually the best place to start.

Other contacts:

- 13 HEALTH: 13 43 25 84

- Child Health Services, Queensland Health

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby Helpline: 1800 882 436

- True Relationships and Reproductive Health

- Australian Breastfeeding Association: 1800 686 268

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

More contacts are listed in your Pregnancy Health Record.

-

Routine tests during pregnancy

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the routine blood tests offered in pregnancy.

These tests are performed to check for anything that may cause problems during pregnancy or after the birth.

Other tests may include a:

- pap smear

- breast check.

More information: Pregnancy Birth and Baby – Blood tests during pregnancy

What if I have a negative blood group?

There are four main blood groups. A, B, AB, and O.

A blood test in early pregnancy tells you which blood group you are, and whether you are Rh positive or Rh negative. Most women (85%) are Rh positive.

If you are Rh negative and your baby is Rh positive it can cause health problems which can be treated.

You will be offered an Anti-D injection at 28 weeks and at 34 weeks of your pregnancy.

You will also be offered an Anti-D injection if you have:

- any vaginal bleeding during your pregnancy

- a miscarriage

- an abortion

- if you have been involved in an accident involving major force to the abdomen

- a medical procedure such as chorionic villous sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis.

You will also require a blood test following birth and may be given an Anti-D injection within 72 hours of your baby's birth if your baby is Rh positive.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines, Parent Information - RhD negative blood type in pregnancy

Testing for gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes only develops in pregnancy.

The condition occurs in two to three of every 100 pregnant women.

How do I find out if I have gestational diabetes?

Due to COVID-19, testing for gestational diabetes might be different to what is usually done.

If you have risk factors for gestational diabetes you will be offered a blood test in the first trimester.

All other women will be offered a blood test around 24–28 weeks of pregnancy. You may have to have a second test where you are given a special glucose drink and have blood samples taken over two hours.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss what is best for you.

For more information about gestational diabetes visit:

-

Ultrasounds during pregnancy

Antenatal ultrasound scans are recommended at certain points during pregnancy to check the:

- number of babies you’re expecting—single, twins or more

- age of your pregnancy (in a dating scan)

- your baby's growth and physical development

- position of the placenta

- length of the cervix (neck of the womb).

We also use scans to monitor:

- the amount of amniotic fluid around the baby

- the health and function of the placenta, which supports your baby’s growth

- any complications, such as bleeding, fluid loss, high blood pressure (hypertension) and diabetes in pregnancy.

Learn more about routine tests and your care during pregnancy.

When you need an ultrasound

Your doctor or midwife will advise you when an ultrasound may be recommended. The following ultrasounds are common in pregnancy.

8–9 weeks dating scan

An early ultrasound at around 8 to 9 weeks is considered to be the best time to confirm the due date, ensure the pregnancy is in the uterus (womb) or for reassurance.

11–13 weeks first trimester screen

An ultrasound (also known as a nuchal translucency scan or early structural assessment) is recommended for all pregnant women. If combined with a blood test (free Beta-HCG and PAPP-A), it can be used to generate a risk for chromosomal abnormalities called a combined first trimester screen.

This is a screening test that will calculate your estimated risk of having a baby with Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities. This ultrasound scan also helps to exclude any major structural abnormalities of your baby early in pregnancy and can be used to screen for preterm preeclampsia if this is offered.

If you decide to use a blood test for genetic screening such as NIPT, it’s also very important to check for physical abnormalities of your baby by having this ultrasound.

18–20 weeks morphology scan

This is an important ultrasound used to rule out major physical abnormalities in your baby and check the location of the placenta.

It is also important to check the length of your cervix at this scan as a short cervix predicts preterm birth. Most parents know this scan as 'the one where we may find out the baby’s sex'.

Where to go for your ultrasounds

You’ll need a referral from a health professional.

You can have your ultrasounds done at a radiology clinic. In some cases, you may be referred to a hospital. Use service finder on the Health Direct website to find your nearest a radiology service.

There may be a charge for your ultrasound depending on where you have it. Some will bulk bill through Medicare. Please talk to a health professional if you can’t pay out of pocket expenses for an ultrasound.

-

Common discomforts in pregnancy

Your body is undergoing many changes during pregnancy and you may experience some health issues along the way.

Many of these issues are a normal part of pregnancy. If you are concerned, talk to your doctor or midwife.

Common discomforts during pregnancy may include:

- morning sickness and severe vomiting

- cramps in your legs and feet

- urinary frequency (needing to pass urine often)

- urinary stress incontinence (leaking urine)

- heartburn and indigestion

- blocked nose

- varicose veins (swollen veins) in your legs

- varicose veins in the genital area

- constipation and haemorrhoids

- backache

- vaginal thrush

- infections (influenza, chickenpox, shingles, slapped face, whooping cough).

More information:

- Pregnancy health problems: what’s common, what’s not

- Common health problems in pregnancy

Sickness and vomiting in pregnancy

You can read these helpful tips for managing morning sickness and find out more information on severe vomiting during pregnancy.

Next section: Looking after yourself and your baby

-

Looking after yourself and your baby

-

Healthy eating during pregnancy

During pregnancy it is important for both you and your baby that you eat well. Your choices of what to eat and drink at this time can affect your health and the health of your baby for many years to come.

There is only a small increase in the amount of food you need to eat while you are pregnant.

However, you do need more of certain nutrients, so it is very important that you make good choices for a nutritious diet.

Important nutrients

Folate (or folic acid) during pregnancy.

Folate is needed for the growth and development of your baby. It is especially important in the month before you fall pregnant and the first trimester (three months) of pregnancy.

A good intake of folate reduces the risks of your baby being born with some abnormalities such as spina bifida (a disorder where the baby’s spinal cord does not form properly).

Dietary sources high in folate include:

- green leafy vegetables – such as broccoli, spinach, bok choy and salad greens

- some fruits – such as avocado, orange, papaya and banana

- cereals and breads with added folic acid.

How much folic acid do you need?

Women planning a pregnancy and in the early stages of pregnancy should eat a variety of folate-containing foods. You should also take a folic acid supplement of 400 micrograms per day at least one month before, and three months after, you become pregnant.

Iron

You need more iron during pregnancy. If you do not have enough iron, you may develop anaemia.

Good sources of iron include:

- lean red meat, pork, chicken and fish

- wholegrain breads and cereals, legumes and green leafy vegetables.

If you are low in iron, your doctor or midwife may suggest taking an iron supplement (tablet or liquid).

You can help your body get iron from the food you eat or drink by:

- including vitamin C with meals (e.g. citrus fruits, tomato, capsicum)

- including animal protein with green leafy vegetables at a meal

- using antacids sparingly.

How much iron do you need?

Pregnant women need 27 mg iron each day. Pregnant women should not eat more than 45 mg iron each day.

Iodine

Adequate iodine in pregnancy is essential for your baby’s growth and brain development.

Iodine is important for your baby’s development in the womb.

Good food sources of iodine include:

- vegetables

- bread with added iodine

- seafood

- eggs.

How much iodine do you need?

Pregnant women should take a supplement containing 150 micrograms of iodine each day.

Multivitamins

A multivitamin during pregnancy is not necessary unless you do not have a balanced diet. Compare what you are eating with the following food group table.

Remember, a folic acid supplement is important during the first trimester of pregnancy, and iodine is essential during pregnancy (and breastfeeding). You may also need to take an iron supplement if your iron levels are low.

You may choose to get these nutrients from individual tablets or from a multivitamin.

Always check with your doctor or midwife before taking any supplements, as an excessive intake of these can be harmful and reduce the absorption of other nutrients.

More information: Queensland Health Nutritional Education Materials Online (NEMO)

Food groups

Food group

Serves per day

(for 19-50 year olds)

1 serve equals

Vegetables and legumes/beans

5

½ cup cooked green or orange vegetables (e.g. broccoli, carrot, pumpkin or spinach)

½ cup cooked, dried or canned beans, chickpeas or lentils (no added salt)

1 cup raw leafy green vegetables

½ medium potato, or other starchy vegetable (sweet potato, taro, or cassava)

½ cup sweet corn

75g other vegetables (e.g. 1 small-medium tomato)

Fruit

2

1 piece medium sized fruit (e.g. apple, banana, orange, pear)

2 pieces smaller fruit (e.g. apricot, kiwi fruit, plums)

1 cup diced, cooked or canned fruit

½ cup 100% juice

30g dried fruit (e.g. 1½ tbsp sultanas, 4 dried apricot halves)

Grain (cereal) foods - mostly wholegrain

8½

1 slice of bread

½ medium bread roll or flat bread

½ cup cooked rice, pasta, noodles, polenta, quinoa, barley, porridge, buckwheat, semolina, cornmeal

⅔ cup breakfast cereal flakes

¼ cup muesli

3 crisp breads

1 crumpet or 1 small English muffin or scone

Lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans

3½

65g cooked lean red meats (e.g. beef, lamb, pork, venison or kangaroo) or ½ cup lean mince, 2 small chops, 2 slices roast meat

80g cooked poultry (e.g. chicken, turkey)

100g cooked fish fillet or 1 small can fish, no added salt, not in brine

2 large eggs (120g)

1 cup (170g) cooked dried beans, lentils, chickpeas, split peas, canned beans

170g tofu

⅓ cup (30g) unsalted nuts, seeds or paste, no added salt

Milk, yogurt, cheese and/or alternatives - mostly reduced fat

2½

1 cup (250ml) milk

40 g (2 slices) hard cheese (e.g. cheddar)

120g ricotta cheese

200g yoghurt

-

How much weight should I gain?

The weight you should aim to gain will depend on what your body mass index (BMI) was before you became pregnant. Use this tool to calculate your BMI.

Your BMI is the number used to work out your recommended amount of weight gain.

Pre-pregnancy BMI

Recommended total gain

Weekly guide in 2nd and 3rd trimester

Less than 18.5 kg/m²

12½ to 18kg

1/2 kg per week

18.5 to 24.9 kg/m²

11½ to 16kg

400g per week

25 to 29.9 kg/m²

7 to 11½ kg

Less than 300g per week

Above 30 kg/m²

5 to 9kg

Less than 300g per week

Pregnancy Weight Gain charts

You may find it easier to follow a pregnancy weight gain chart. The charts are divided in two groups:

- Pregnancy weight gain chart for BMI less than 25kg/m2

- Pregnancy weight gain chart for BMI 25kg/m2 or over.

More information: How much weight should I gain while pregnant.

-

Food Safety in pregnancy

Listeria in pregnancy

Listeria is a bacteria found in some foods, which can cause an infection called listeriosis. If passed on to your unborn baby it can cause premature birth, miscarriage or damage. Throughout your pregnancy, it is important to avoid foods that have a high risk of containing listeria.

Foods that might contain Listeria and should be avoided include:

- unpasteurised dairy products

- soft cheeses such as brie, camembert, ricotta, and fresh fetta, unless they are cooked (yellow, hard cheese, and processed packaged cheese are safe)

- soft serve ice cream and thick shakes

- all paté

- ready-to-eat cold meats, including deli and packaged meats (e.g. ham, salami, cooked chicken)

- ready-to-eat salads (from salad bars, buffets, supermarkets etc.)

- raw or smoked seafood (including oysters, salmon, sashimi, sushi)

- undercooked meats (e.g. raw steak) and eggs

- ready to eat prawns.

Eating fish during pregnancy

Fish is a safe and important part of a healthy diet. It is an excellent source of protein, low in saturated fat, high in omega 3 fish oils and a good source of iodine.

However, some types of fish should be restricted as they may contain higher levels of mercury.

Recommendations for pregnant women

(1 serve = 150g)

1 serve per fortnight of shark (flake) or billfish (swordfish/broadbill and marlin) and NO other fish that fortnight

or

1 serve per week of Orange Roughy (Deep Sea Perch) or catfish and NO other fish that week

or

2–3 serves per week of any other fish and seafood not listed above.

Eating eggs during pregnancy

Do not eat raw or undercooked eggs. Eggs must be cooked through so that both the white and yolk are hard.

Food safety tips

Here are some tips for keeping your food safe:

- choose freshly cooked and freshly prepared food

- thaw food in the fridge or defrost in the microwave

- cool left-over food in the fridge, rather than the bench

- wash your hands, chopping boards and knives after handling raw food

- make sure hot food is very hot (above 60 degrees Celsius) and cold foods are very cold (below 5 degrees Celsius) – both at home and when eating out

- make sure all food is fresh and eaten within the use-by date

- wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly before use

- eat leftovers within 24 hours and reheat foods to steaming hot

- heat leftovers to above 74 degrees Celsius, for at least two minutes

- cook all meat, chicken, fish, and eggs thoroughly

- never re-freeze food once it has been thawed or reheated.

More information on healthy eating during pregnancy, including fact sheets and resources suitable for Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Maori, and Pacific Islander women are available through Queensland Health Nutritional Education Materials Online (NEMO).

-

Exercise during pregnancy

It’s great to be active and stay fit while you’re pregnant.

Check with your doctor or midwife to make sure there are no health problems to prevent you from exercising.

If there are no problems, try to do 30 minutes of moderate exercise (like walking) on most days of the week.

Regular exercise can help you:

- stay at a healthy weight

- relax

- be stronger and fitter – which is good for coping with pregnancy, labour and being a parent

- decrease discomforts like back pain and varicose veins – which can affect some pregnant women.

If you haven’t been physically active before

Pregnancy can increase your risk of injury because your joints loosen up to let your body grow and make it easier to give birth.

You can prevent injury in pregnancy by avoiding high impact exercise like jumping up and down, repetitive bouncing movements, and any movements that over-stretch your hip, knee, ankle or elbow joints.

Stop exercising if you experience:

- dizziness

- vaginal bleeding

- contractions

- pain

- shortness of breath

- decreased baby movements

- “waters are leaking”.

Read more information on pregnancy and exercise.

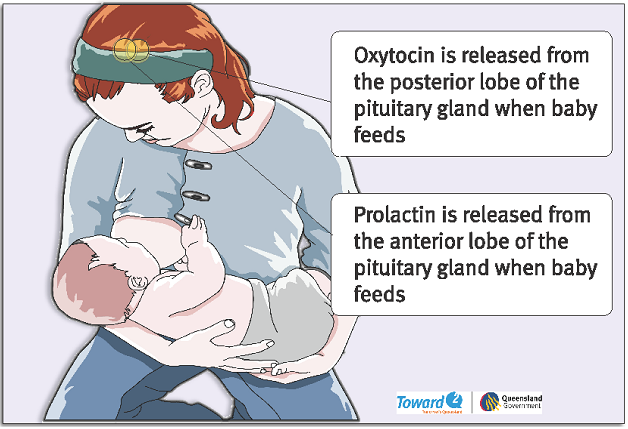

Pelvic floor exercises

By performing pelvic floor exercises, you can strengthen muscles to help reduce or avoid stress incontinence after pregnancy.

Incontinence is a common but treatable condition – view the video below or visit the Continence Foundation of Australia for more information.

To learn safe exercises, you can download a copy of Pelvic floor health for expectant and new mums from the Continence Foundation of Australia.

One in three women who ever had a baby wet themselves - consumer education video

This video answers the question about why a woman has an increased risk of leaking urine (urinary incontinence) after childbirth. Find out how to prevent this from happening, how to treat the condition and where to get help.

-

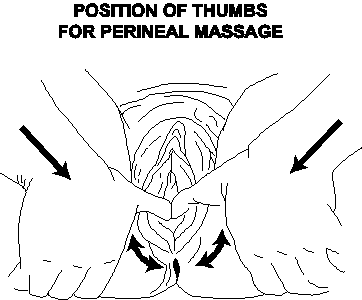

Perineal massage

From about 35 weeks you can start preparing for your labour and birth with perineal massage.

Research has shown that massaging the perineum during late pregnancy may encourage elasticity and reduce the risk of tearing during childbirth.

Where is my perineum?

The perineum is the area between the vaginal opening and anus. Some women choose to use perineal massage as a way of (hopefully) reducing their risk of perineal trauma during childbirth.

When can I start perineal massage?

You can start massage from about 35 weeks and perform no more than three times per fortnight.

How should I do perineal massage?

- Gently insert thumbs or 1-2 fingers, 3-5 cm into the vagina, and firmly sweep in a downward and side to side motion for five minutes, using a natural oil for lubrication, (Avoid nut-based oils if known allergies. Do not use baby oil, mineral oil or petroleum jelly).

- You may feel a burning sensation which will diminish over time.

- Do not massage if you have active genital herpes or a vaginal infection present.

- Most women consider their partner’s involvement as positive.

Ask your doctor or midwife for more information.

-

Medications, alcohol, and smoking during pregnancy

Medications

Not all medicines are safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

This includes medicines that are prescribed, natural supplements, or over the counter from the pharmacy or supermarket.

Make sure you tell your doctor or midwife, and pharmacist, about all the medicines you are taking – especially if you:

- have an existing medical condition

- are taking an over the counter or prescribed medication

- are taking alternative and complementary therapies

- are using illicit drugs - seek urgent advice from a health professional.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines – Using drugs in pregnancy

Drinking alcohol during pregnancy

The safest choice for your baby is to not drink any alcohol.

The risk of damage to your baby increases the more you drink, and binge drinking is especially harmful.

There is no safe amount of alcohol to drink when you’re pregnant.

What if you drank before you knew you were pregnant?

If you drank small amounts of alcohol before you knew you were pregnant, be reassured that the risk of harm to your baby is low.

More information: The National Organisation for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alcohol and Pregnancy

Smoking during pregnancy

Stop smoking during pregnancy and you and your baby will immediately feel the benefits.

Toxic chemicals are absorbed into your bloodstream and passed on to your baby through the umbilical cord. If you are unable to stop smoking, cut down as much as you can.

Smoking while pregnant increases your risk of:

- ectopic pregnancy

- miscarriage

- premature labour

- complications during birth.

- sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

- low birth weight

- infections and other health problems

- asthma and other breathing difficulties

- behavioural problems.

Smoking while pregnant can increase your baby’s risk of problems after they are born:

For advice and support visit Quit HQ or call Quitline on 13 78 48.

More information: Pregnancy Birth and Baby - Smoking and pregnancy

Helpful hints to stop smoking

When you feel the urge to smoke:

- distract yourself for five to 10 minutes so the craving can pass

- relax and take some deep breaths

- drink a glass of water

- call a friend

- practice your pelvic floor exercises

- change the habits you associate with smoking

- take it a day at a time and reward yourself for success

- visit Quit HQ or call Quitline on 13 78 48.

More information: Coping with quitting and staying smoke- and vape-free

-

Vaccinations during pregnancy

Immunisation is a simple and effective way to protect yourself and your baby from certain infections.

During pregnancy, it is recommended that you have the following vaccinations.

‘Flu’ (Influenza)

Influenza can cause serious illness and being pregnant increases the risk of influenza complications, especially with the H1N1 influenza virus. Influenza vaccine is safe and can be administered before, during or after pregnancy.

Whooping cough (Pertussis)

Whooping cough can cause serious illness and even death in babies less than six months old. It is now recommended that all pregnant women receive a pertussis (whooping cough) vaccination during their third trimester (ideally at 28 weeks) of every pregnancy.

Other vaccinations

Check with your doctor whether you have immunity against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox – as well as influenza and whooping cough.

More information:

-

Infections and precautions in pregnancy

Coronavirus and pregnancy

Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a new virus and we are still learning how it may affect you and your baby.

To reduce your chance of getting the virus, follow these prevention measures:

- wash your hands regularly and frequently—use soap and water for 20 seconds or alcohol-based hand sanitiser/gel

- use social and physical distancing (stay 1.5 metres away from other people)

- avoid anyone who has a fever, cough or symptoms of a cold or chest infection

- avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

Cytomegalovirus

Read about the common viral infection cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Gardening during pregnancy

It is important to wear gloves when gardening and wash hands afterwards.

Toxoplasmosis

Cats can be a source of Toxoplasmosis—a serious infection that can cause defects or death in your baby. It is important to avoid contact with cats and use gloves when handling cat litter.

Next section: Mental wellbeing during pregnancy

-

Mental wellbeing during pregnancy

Pregnancy, birth and early parenthood are times of great change.

During pregnancy most women experience a range of emotions. Your pregnancy hormones may make you more emotional than usual. You may worry about whether your baby will be normal and how you will cope with labour. It helps if you can talk openly about any concerns with your partner or a close friend.

Common concerns of pregnant women can be:

- will my baby be normal?

- worrying about labour

- changing body, emotions and relationships.

Read more about pregnancy and new parents and visit Dear Mind for many ways to strengthen your mental wellbeing.

Depression and anxiety during pregnancy

Depression and anxiety can occur at any time in your life and can often come to the surface with major events like pregnancy or having a baby.

Around 12% of pregnant women in Australia experience antenatal depression (depression during pregnancy). The risk is higher if you have been depressed in the past.

It is important to keep a check on how you are feeling emotionally and discuss any concerns with your health professional. Let someone know if you are:

- feeling low, anxious or tense very often

- feeling guilty

- feeling that things are hopeless

- not enjoying things you normally do

- crying all the time

- irritable

- finding it hard to sleep, concentrate or make decisions

- wanting to harm yourself.

Read more on perinatal anxiety or find a health professional at Beyond Blue.

Mental wellbeing for partners

Partners share many of the experiences of pregnancy.

Partners also experience the worries, problems, pleasure, and the waiting. Sometimes partners may also have issues of their own to work out.

You can read and share information from Dad’s guide to fatherhood and Dads guide to pregnancy.

There is also information in many languages from the Multicultural Health Communication Service.

Where to get help

If you or someone you know is showing signs of depression or anxiety, there are places you can go to for help.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby Helpline: 1800 882 436

Beyond Blue – Pregnancy and new parents: 1300 224 636

MUMspace – support for the emotional health of new mums, at every step.

Prenatal Anxiety and Depression Australia (PANDA): 1300 726 306

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Mensline Australia: 1300 789 978

Sane Australia Helpline: 1800 18 7263

White Cloud Foundation: 1300 702 926

-

Depression and anxiety during pregnancy

Depression and anxiety can occur at any time in your life and can often come to the surface with major events like pregnancy or having a baby.

Around 12% of pregnant women in Australia experience antenatal depression (depression during pregnancy). The risk is higher if you have been depressed in the past.

It is important to keep a check on how you are feeling emotionally and discuss any concerns with your health professional. Let someone know if you are:

- feeling low, anxious or tense very often

- feeling guilty

- feeling that things are hopeless

- not enjoying things you normally do

- crying all the time

- irritable

- finding it hard to sleep, concentrate or make decisions

- wanting to harm yourself.

Read more on perinatal anxiety or find a health professional at Beyond Blue

-

Mental wellbeing for partners

Partners share many of the experiences of pregnancy.

Partners also experience the worries, problems, pleasure, and the waiting. Sometimes partners may also have issues of their own to work out.

You can read and share information from Dad’s guide to fatherhood and Dads guide to pregnancy.

There is also information in many languages from the Multicultural Health Communication Service.

-

Where to get help

If you or someone you know is showing signs of depression or anxiety, there are places you can go to for help.

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby Helpline: 1800 882 436

- Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636

- Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Association (PANDA): 1300 726 306

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- MensLine Australia: 1300 78 99 78

- Sane Australia - Support services: 1800 18 7263

- White Cloud Foundation: 1300 702 926

- Black Dog Institute

- MUMspace

Next section: Journey of labour

-

Journey of labour

-

Preparing for labour and birth

In addition to the natural physical preparation your body makes for birth, you may also find yourself preparing emotionally.

You may:

- feel a strong need to be ready

- find yourself worrying more than usual

- be concerned about making it through labour, or whether your waters will break in public

- be concerned about whether your partner will be able to help you, or whether you will have a bowel movement during the birth and how your partner might react to that

- be worried about the safety of you and your baby during birth

- be worried about having a caesarean birth.

These concerns are common. Discuss your concerns with your midwife or doctor, so you can feel prepared and informed before labour starts.

Your birth preferences

Preparation for labour starts during pregnancy.

Your birth preferences (sometimes known as a birth plan) is a written list of what you would like to happen when you are in labour and give birth.

Birth preferences may include:

- who you would like with you in labour

- what position you would like to give birth in

- what comfort measures you might use as your pain relief options.

It is important to stay flexible

Remember that things may not go according to plan.

There may be complications, or you may change your mind about something. Think about what is important to you for your birth.

Other questions to consider when deciding on your birth preferences may be:

- what if I need a caesarean birth?

- what is the usual practice for an induction of labour?

- what equipment may be used in my labour and for the birth of my baby, and why?

- do I have any cultural or religious needs around giving birth?

- can I expect to hold my baby skin-to-skin after he/she is born?

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby - Making a birth plan

-

Who will support you in labour

It can be helpful to have people around you who can provide both emotional and physical support during labour.

Hospitals usually allow two support people with you in labour. This could be your partner, another family member or a friend.

- Some women choose to hire a doula or birth attendant to support them during labour.

- A doula is not a member of your maternity team but is experienced in supporting women and their partners during labour.

- You can check with your midwife or doctor regarding policies about support persons.

Studies show that women who have someone with them right through labour have a more positive experience of labour and are less likely to need medication for pain relief.

Please note: Due to COVID-19, the number of support people you can have with you during labour and birth may be limited. It is suggested that you choose someone who can stay with you for the whole time.

Being a birth partner

There are many things a birth partner can do to provide support.

They can:

- keep you company and help to pass the time during the early stages

- hold your hand, wipe your face, give you sips of water

- massage your back and shoulders, help you to move or change position, or anything else that helps

- comfort you as your labour progresses and your contractions get stronger

- remind you how to use relaxation and breathing techniques, perhaps breathing with you if it helps

- support your decisions, such as the pain relief methods that you choose

- help you explain to the midwife or doctor what you need – and the other way around – which can help

- help you feel much more in control of the situation

- (if possible) cut the umbilical cord – you can talk to your midwife about this.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Being a birth support partner

-

How your body prepares for labour

Your body is getting ready for childbirth throughout your pregnancy, especially in the last few weeks with final preparation.

The pelvis is made up of two large bones joined by cartilage and ligaments – at two joints in the woman's lower back at the sacrum (called the sacroiliac joints) and at the front symphysis pubis bone.

During late pregnancy a hormone softens and relaxes these ligaments. This gives the pelvic bones the ability to stretch and open more easily for the birth of your baby. It is common in late pregnancy to experience lower back pain, or you may notice that you have a ‘pregnancy waddle’ when walking, due to these changes.

Braxton Hicks contractions

Braxton Hicks are also called ‘practice contractions’ because they are preparation for labour.

Braxton Hicks contractions can begin as early as the second trimester. However, they are most commonly experienced in the third trimester. When this happens, the muscles of the uterus tighten for approximately 30 to 60 seconds and sometimes as long as two minutes. If you have concerns or think you might be in labour, contact your midwife or the hospital.

Braxton Hicks are described as:

- irregular in intensity

- infrequent

- unpredictable

- non-rhythmic

- more uncomfortable than painful (although for some women Braxton Hicks can feel painful)

- they do not increase in intensity, or frequency

- they taper off and then disappear altogether

if your contractions are easing up in any way, they are most likely Braxton Hicks.

How your baby prepares for labour

Your baby may begin moving lower in the pelvis, which is called engagement.

How will I know if baby’s head is engaged?

You might notice this as increasing pressure in your lower abdomen, or you might notice that breathing becomes easier.

- For first time mothers, engagement usually occurs about 36 weeks of pregnancy.

- For second-time mothers, engagement may not occur until after labour begins.

Your baby is designed for the birth process

The baby's skull bones are divided into five plates that cross over during labour, making their head smaller by moulding to fit the birth canal. Mother and baby work together during labour.

-

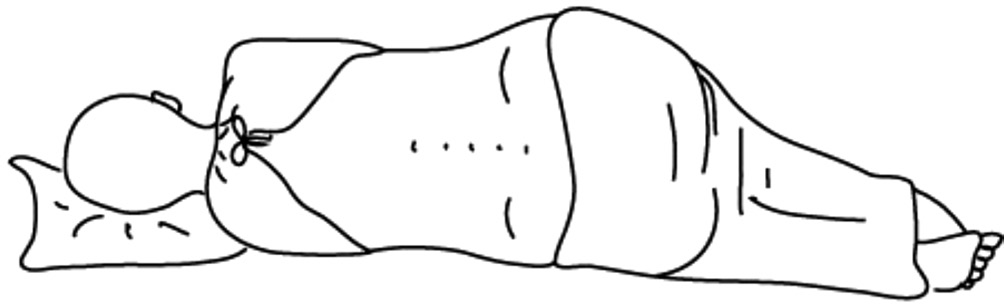

Getting baby in the right position for birth

There are things you can do during pregnancy to encourage baby into the best position for labour.

How you sit and use your body can affect the position of your baby in the uterus.

While this does not matter so much during early pregnancy, later on it can affect the position that the baby moves into (in the pelvis).

Presentation during labour refers to which part of the baby enters the birth canal first. Normally, the crown of the head will enter first, which is known as cephalic presentation. Other forms of presentation such as breech presentation may cause difficulties with birth.

Once the baby is head down, the best position for a labour is the anterior position.

Anterior position means the baby’s head enters the pelvis facing your back.

This is the ideal and most common position for birth (see image). When baby is in the anterior position, the smallest dimension of the baby’s head leads the way through the birth canal.

What can I do to get my baby in the best position?

You can use different positions during your pregnancy to give you the best chance of ‘optimally positioning your baby’ prior to labour.

Positions include:

- hands and knees, for as long as comfortable, or sitting on the floor

- lying on your side is a better option when on the lounge, than sitting slumped and relaxed back into the lounge chair

- sitting on a low stool or fit ball, where you are in a supported squat.

What if baby is in the posterior position

Posterior position means the baby’s head enters the pelvis facing your stomach instead of your back.

It’s good to know that most babies will turn around during labour, but some don't.

How can this affect my labour?

If your baby is in the posterior position when labour starts, it can lead to a longer labour with more backache.

If baby doesn’t turn, you may be able to push baby out yourself or your doctor may need to turn the baby’s head and/or help your birth with forceps or a vacuum cup.

-

When to seek advice during pregnancy

Seek advice from your doctor or midwife, or come to hospital if you:

- have bright red, fresh blood loss

- feel your baby’s movements have changed, or you are worried about your baby’s movements

- feel unwell (flu like symptoms) or are experiencing a burning or stinging sensation when passing urine

- have severe back pain

- have uncontrollable diarrhoea and or vomiting

- feel your stomach is tender, or you experience severe indigestion pain that you have not had before

- feel faint or have fainted

- are experiencing signs of labour (call early if you have a planned caesarean birth).

IMPORTANT: Call the hospital any time, day or night, to speak with a midwife. You will be asked questions about what is happening. You can then plan when to come into hospital.

Bring your Pregnancy Health Record with you.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – What happens to your body during childbirth

-

Final preparations for labour

For mother:

- have your bag packed for hospital from 36 weeks

- go through your birth preferences with your birthing partner(s) and doctor or midwife

- practice your pelvic floor exercises and do some gentle exercise.

For birth partner:

- keep a list of necessary telephone numbers

- check the route to the hospital and have money ready for car parking

- have a labour bag packed for yourself

- make sure your mobile phone is always fully charged.

What to bring to hospital

For mother:

- Pregnancy health record

- maternity bras

- two packs of maternity pads

- current medication

- own pillow (if desired) – labelled

- clothes for labour – old t-shirt, comfortable clothing, warm socks, old underwear, track pants for after birth

- massage oil or lotion

- spray bottle (non-aerosol) for cooling

- tissues and toiletries – soap, shampoo, toothpaste, tooth brush

- food such as barley sugar, jelly beans, fruit bars, glucose drinks

- thongs or slippers

- lip cream for dry lips.

For baby:

- two-dozen newborn size nappies

- six newborn singlets

- six newborn jumpsuits

- six to eight bunny rugs or cotton wraps

- baby wipes / cotton wool

- three face washers for baby bath.

Other:

- camera (charged)

- mobile phone or phone card

- music for use during labour

- baby car seat for discharge

- pen.

Next section: Stages of labour

-

Stages of labour

-

Baby’s journey of labour

The human pelvis has a complex shape, making your baby negotiate several manoeuvres during labour and birth.

Every mother’s pelvis is widest side to side at the entrance – because of this, most babies enter the pelvis looking left or right. The exit from the pelvis is widest from front to back, so babies almost always turn face up or face down.

These manoeuvres occur from forces of labour and the resistance provided by the birth canal. In addition to making these turning manoeuvres, the baby is simultaneously descending further down the vagina.

Finally, the top of your baby’s head appears (crowns), stretching your vaginal opening. When the vulva has stretched enough, the baby’s head will emerge – usually by extending the head, lifting its chin off the chest and thus emerging from under your pubic bone.

The baby usually emerges face down but will turn to one side very quickly as the shoulders turn to take the same route. The rest of the body is born and then you can hold your new baby!

-

Hormones during labour

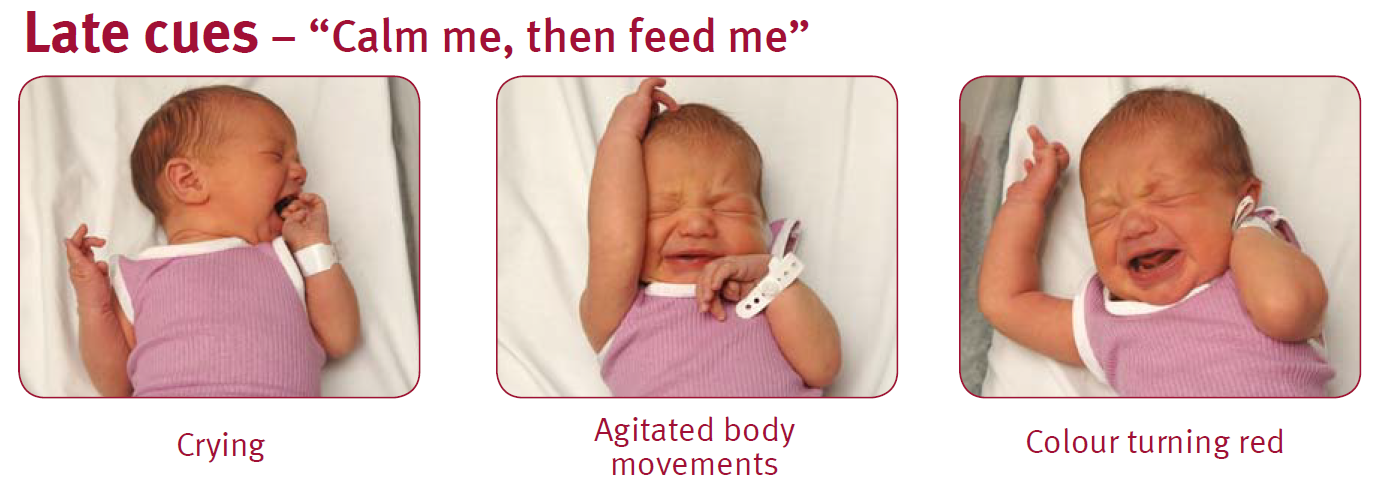

Oxytocin: Known as the hormone of love, oxytocin is secreted during sex, after ovulation and during labour, birth and breastfeeding. It creates nurturing and loving feelings.

Endorphins: Endorphins are produced in response to pain and stress. Endorphins have calming and pain-relieving effects. As labour progresses and pain intensifies, endorphin levels steadily increase in unmedicated labours.

Adrenaline: Adrenaline is also known as the ‘fight or flight’ hormone. Adrenaline is secreted in response to stress, fear and extreme pain. If a woman experiences these feelings during labour, too much adrenaline may be produced which can slow labour.

More information: Hormones in labour: oxytocin and the others – how they work

-

Stages of labour

Labour is divided into four stages.

- The first stage of labour is the slow opening of your cervix.

- The second stage is the birth of your baby.

- The third stage is separation and birth of the placenta.

- The fourth stage is the first two hours after birth.

The main signs of labour starting are:

- contractions

- a ‘show’ (a mucous blood-tinged vaginal discharge)

- waters breaking.

-

First stage of labour

The first stage of labour is made up of three different phases and involves the thinning of the cervix and its dilation to around 10 centimetres.

Latent phase

- Generally, this stage is the longest and the least painful part of labour.

- The cervix thins out and dilates from zero up to four–six centimetres.

- This may occur over days or hours and be accompanied by mild contractions.

- The contractions may be regularly or irregularly spaced, or you might not notice them at all.

Active phase

- The next phase is marked by strong, painful contractions that tend to occur three or four minutes apart, and last from 30 to 60 seconds.

- The cervix dilates from four–six to eight centimetres.

Transition

- The cervix dilates from eight to 10 centimetres (that is, fully dilated).

- These contractions can become more intense, painful and frequent. It may feel as though the contractions are no longer separate but running into each other.

- It is not unusual to feel out of control and even a strong urge to go to the toilet as the baby’s head moves down the birth canal and pushes against the rectum.

Throughout the first stage of labour, careful monitoring and recording of your wellbeing, your baby’s wellbeing, and the progress of your labour, is important. This helps us to know whether your labour is progressing normally, to recognise any problems early and for clear communication. Ideally, you will experience the latent phase in the comfort of your home. You may wish to come to hospital as you move through the active phase.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Early labour

What can I do in the active stage of labour?

Birth partner’s role

- Remind your partner to go to the toilet.

- Help her with changing positions.

- It might help to dim the lights or play some music.

- Support her in any decisions she makes about pain relief.

- Keep yourself relaxed as possible and look after your needs.

- Sometimes humour can lighten the atmosphere when appropriate.

Helping yourself in first stage

- Stay well hydrated.

- Eat lightly during labour; your digestive system naturally moves more slowly, and you may find that you become nauseated. Some easily digested foods include fruits, yogurt or toast.

- Choose positions of comfort; you might find that your body instinctively moves to certain positions during contractions.

- Slow swaying movements may also help during contractions.

- Standing helps your body and your baby work with gravity and encourages the downward movement of your baby through the pelvis.

- Remember – an empty bladder is more comfortable and gives your baby more space to move down.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Giving birth - first stage of labour

-

Second stage of labour

The second stage of labour is the birth of your baby.

The second stage of labour starts when your cervix is fully dilated, and you will usually have a strong urge to push because of the pressure your baby’s head is placing on your pelvic area.

At this stage your baby is moving from your uterus into your vagina and out into the world.

The second stage can last from 10 minutes to two hours.

What can I do in the second stage?

Helping yourself during the second stage

- Push when you have a contraction and relax in between.

- It is more effective to get two or three pushes in with each contraction, breathing in between, rather than one long push.

- Being upright allows gravity to help you.

- Relax your pelvic floor muscles around the vaginal opening.

- Your midwife may apply warm compresses to your perineum for comfort and to reduce tearing.

Birth partner’s role

- Help your partner into a comfortable position.

- Your encouragement is important but avoid cheerleading.

- It can be helpful to repeat the midwife’s advice to your partner in a calm steady voice.

- Offer your partner sips of water or ice.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Giving birth - second stage of labour

-

Third stage of labour

After the birth of your baby, your uterus gently contracts to loosen and push out the placenta. This may occur five to 30 minutes after the birth of your baby.

The muscles of the uterus continue to contract to stop the bleeding. This process is always associated with a moderate blood loss – up to 500 millilitres. In this stage of labour, one of the potential problems is excessive bleeding (postpartum haemorrhage), which can result in anaemia and fatigue. This is why the third stage is carefully supervised.

There are two approaches to managing the third stage:

- natural (also known as physiological or expectant) management, or

- active management.

Natural third stage

What is a natural third stage?

A physiological or natural third stage means that you wait for the placenta to be delivered naturally.

After your baby's birth, your midwife will delay clamping the umbilical cord to allow oxygenated blood to pulse from the placenta to your baby.

Your uterus (womb) will contract, and the placenta will peel away from the wall of your uterus. The placenta will then drop down into your vagina, ready for you to push it out.

Delayed cord clamping

For baby

The benefits of delayed cord clamping for the baby include a normal, healthy blood volume for the transition to life outside the womb; and a full count of red blood cells, stem cells and immune cells which results in higher iron stores in the baby for up to six months.

For mother

Delayed clamping keeps the mother-baby unit intact and can prevent complications with delivering the placenta.

Active (or managed) third stage

Benefits of an active third stage

The advantage of an active third stage is the lower risk of very heavy bleeding immediately after the birth. Your midwife or doctor will recommend you have an active third stage if you had complications during pregnancy or labour, such as:

- twin pregnancy

- polyhydramnios

- heavy bleeding during pregnancy or in labour

- a history of retained placenta

- a low-lying placenta

- anaemia

- an induced or very long labour

- an assisted birth or caesarean birth.

Active third stage

Immediately after the birth of your baby, the midwife or doctor gives you (with your consent) an injection of oxytocin, clamps and cuts the umbilical cord, and then carefully pulls on the cord to speed up delivery of the placenta.

Modified active third stage

This is a combination of active and natural. It is similar to active third stage but it includes delayed cord clamping.

-

The fourth stage

Baby’s birthday

After the birth, you and your partner will be given time with your baby so that you can get to know one another.

- It’s important that you and your baby stay together, skin to skin, ideally for the first two hours after birth.

- Your baby will be examined, weighed, measured and given identification bracelet/s.

- If you consent, baby will also be given vitamin K as an injection or orally.

- Your baby may be dressed and wrapped in a warm blanket.

- You may then be transferred to the postnatal wards or you may request an early discharge if you and baby are well.

Checks after your baby is born

While you are holding your baby, your midwife or doctor will do a check called an ‘APGAR score’.

The APGAR score will be done twice, at one minute and five minutes after birth. You probably won’t even notice it’s being done, as the midwife can do this while baby and mother are skin to skin.

It helps the midwife or doctor to know whether your baby needs additional care following birth.

The APGAR score is based on the baby’s:

- breathing rate

- heart rate

- skin colour

- muscle tone

- reflexes.

Blood loss after birth

Blood loss after birth is normal.

Bleeding in the days or weeks after birth (also called lochia) is completely normal and occurs regardless of whether you have a vaginal birth or caesarean birth.

What is normal blood loss after birth?

Women’s experiences of bleeding after birth vary considerably. In the first few days after birth, most women experience moderate to heavy bleeding. Over the first few days to weeks this bleeding will gradually decrease and will change colour.

Most women will stop bleeding between four and six weeks after birth. It is also common for bleeding to be heavier after breastfeeding.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Next section: Birth - frequently asked questions

-

Birth - frequently asked questions

-

When does labour start?

A normal pregnancy lasts 38–42 weeks.

Every labour and birth is different. It is still not known exactly what happens to start labour.

The average length of pregnancy is 280 days or 40 weeks, from the first day of your last menstrual period. The medical term for the due date is estimated date of delivery (EDD).

Did you know that only about four percent of women give birth on their baby’s due date!

-

When will my waters break?

Most women’s waters break during labour, but it can also happen before labour starts.

When your waters break, the amniotic sac breaks, and the fluid drains out through your vagina. It can be a gush or a slow trickle.

The fluid will usually be clear but can be yellow or straw coloured. If it is green or red in colour, there may be a problem.

What should I do when my waters break?

Whatever the colour, you should put a pad on and call your midwife or the hospital who will advise you on when to come into hospital.

-

How long does labour last?

All labours are different. Every labour is unique. The length of each person’s labour is different.

How quickly your labour progresses will depend on the baby descending (going down through the pelvis) and the cervix dilating (opening up) with strong, regular contractions.

On average for your first baby, the:

- first stage of labour can last from 10 to 14 hours

- second stage of labour can take one to two hours to push your baby out

- third stage can last five to 45 minutes

- fourth stage is the first two hours after birth.

If you have had a baby before, the:

- first stage of labour can last from five to eight hours

- second stage can last from five minutes to an hour.

-

What is pre-labour?

For up to a week before labour starts, you may notice that your body is preparing for labour.

Some women will notice:

- an increase in vaginal discharge (clear)

- a plug of mucous (‘show’) may be released from the cervix – perhaps with a streak of blood

- feeling unusually energetic (nesting instinct)

- frequent Braxton Hicks ‘practice’ contractions.

-

What do contractions feel like?

Women describe and experience contractions in different ways.

They may feel like:

- lower abdominal cramps that feel like period pain

- persistent dull lower backache

- inner thigh pain that may run down your legs.

At first these contractions are short and may be far apart – sometimes as much as 30 minutes apart.

As your labour progresses, they will get longer, stronger and closer together; until they last for about a minute and are coming faster, about every two or three minutes.

-

How do I time contractions?

From the beginning of one contraction until the next one begins. You can also time how long the contractions last.

The frequency of your contractions

Using a watch or clock, measure the frequency of your contractions by timing them from the beginning of one to the beginning of the next.

True labour will develop into a regular pattern, with your contractions growing closer together. In false labour, contractions remain irregular.

The length of your contractions

Measure the duration of each contraction by timing when it begins and when it stops. True contractions last about 30 seconds at the onset and get progressively longer up to 75 seconds and stronger. False labour contractions vary in length and intensity.

-

When do I come to hospital?

Seek advice or come to hospital if:

- Your waters break – put on a sanitary pad, note the time, the colour and amount of water then call your midwife or the hospital.

- Your contractions become painful, regular and are occurring at least five minutes apart (this timing will depend on your personal history, circumstances and will be discussed in your pregnancy).

- Labour has commenced and you have been advised to attend hospital early.

- You are experiencing signs of labour and you have a planned caesarean birth.

- You have a known medical or pregnancy condition that means you will require closer monitoring than usual in labour

- Your baby’s movements have changed, or you are worried about your baby’s movements.

Call ‘000’ for an ambulance if:

- You think your labour is progressing very quickly and you won’t make it to hospital.

- You experience heavy bleeding (similar to first day of a period) or have a severe headache and blurred vision.

-

What do I bring to hospital?

See ‘Final preparations for labour’.

-

What happens when I get to hospital?

When you arrive, a midwife will talk about what is happening to you and discuss your birth preferences.

The midwife will:

- ensure you have an identification band on your wrist

- check your temperature, pulse and blood pressure

- check the baby’s position by feeling your abdomen

- listen to the baby’s heart rate

- time your contractions

- with your consent, may do an internal (vaginal) examination to see how much your cervix has opened, and to check the baby’s position.

-

What if my labour is progressing slowly?

What can I do if labour is progressing slowly?

It’s good if you can relax and stay calm – anxiety can slow things down.

The midwife may suggest:

- changing position

- walking around – movement can encourage contractions

- a warm shower or bath

- a back rub

- a nap to regain your energy

- something to eat or drink

- options for pain relief – if you’re very tired or have pain.

-

What is the best position for giving birth?

Kneeling, on the bed or floor, leaning against a large pile of pillows, or supported by a partner. Some women may feel more comfortable with one knee up.

Squatting, supported by partner behind, or holding onto a bar. The woman should stand to rest between contractions. This may not be appropriate for women who have had epidurals.

Sitting, such as on a toilet or birth stool, with the legs wide apart and leaning forwards with the arms supported on the thighs, or by a partner.

-

What is an episiotomy?

An episiotomy is a surgical cut in the woman’s perineum (area between the vagina and anus) during birth.

You may need an episiotomy (with your consent) when for some reason, related to your baby or you, your doctor or midwife believes there is a chance that your perineum may tear when the baby’s head comes through during the second stage of labour. This is more likely to occur when forceps or a vacuum assistance is required.

Research has shown that the selective use of episiotomy may reduce a more severe vaginal or perineal tear.

-

How will my baby be monitored during labour?

During labour, your baby's heart rate will be checked regularly.

If you have had a healthy pregnancy and there are no problems at the onset of labour, your baby's heart will be listened to every 15 to 30 minutes using a small hand-held Doppler ultrasound device. This equipment can be used regardless of the position you are in, even in the shower.

If you had problems during pregnancy or if problems arise during your labour, your baby’s heart rate may be monitored continuously using a cardiotocograph (CTG).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

-

What is a CTG?

A CTG (cardiotocograph) involves having two plastic disks (receivers) strapped to your abdomen and held in place by two belts. The receivers are attached to a machine, which may limit your movement. Some machines are wireless, enabling you to move around freely while you are being monitored. This is known as telemetry.

-

Why do I need internal (vaginal) examinations?

What happens during a vaginal examination?

When a woman's cervix thins during labour it is referred to as effacing. When her cervix is opening it is called dilating.

These cervical changes can be measured by the caregiver doing a vaginal examination with their gloved fingers during labour, often referred to as a VE.

During labour, vaginal examinations are usually carried out after a contraction finishes and when the woman says she is ready.

-

Can I take my placenta home?

Request to take the placenta home

The birth placenta holds significant value in some cultures and for some people. It is not uncommon for people to bring their baby’s placenta home, bury it in the garden and plant a tree above it.

You have the right to take your placenta home – speak to your midwife about the policy and how the hospital will support you.

-

How do I register my baby’s birth?

After baby is born, you will be given a birth registration pack.

Information includes:

- how to register your baby’s birth

- how to order a birth certificate/extract or commemorative birth certificate.

In the case of same sex female parents, only one parent can be registered as the baby's mother.

More information:

Next section: When complications occur

-

When complications occur

-

Plans may change

Every woman is different. Every labour is different.

Sometimes pregnancy, labour and birth may not go as planned. The reasons are usually complex.

This module will discuss the following important topics:

- pre-eclampsia

- preterm birth

- multiple birth

- breech

- overdue pregnancy

- monitoring in labour.

- concerns for baby in labour

- antibiotics during labour

- blood loss after birth

Always talk to your doctor or midwife if you are concerned.

-

Pre-eclampsia

Symptoms of pre-eclampsia may include:

- high blood pressure and the presence of protein in the urine

- severe headaches

- sudden swelling, weight gain

- blurred vision or seeing ‘stars’ or ‘spots’

- a sense of feeling very unwell.

What is pre-eclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia is a serious disorder of pregnancy characterised by high blood pressure and serious complications of other organs in the body. Without treatment, seizures can develop. This can be fatal for mother and baby.

It is the most serious medical complication of pregnancy, affecting around five to 10% of all pregnancies in Australia. Researchers still do not know exactly why it happens in some pregnancies.

Regular antenatal checks are vital to keep a check on your blood pressure. Sometimes medication is needed. The onset of pre-eclampsia can be fast! If you experience any of the symptoms, seek medical assistance urgently.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Pre-eclampsia

-

Preterm birth

What is a preterm (premature) birth?

A preterm birth is one that happens before 37 weeks of pregnancy. In about half of all preterm births, the cause is unknown.

Factors that increase the likelihood of a premature birth can be:

- a previous premature birth

- some conditions of the uterus or cervix, such as fibroids or a weakened cervix

- a multiple pregnancy

- a maternal infection

- some maternal medical conditions such as pre-eclampsia.

If babies are premature, they are likely to need extra care at birth.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Preterm labour and birth

-

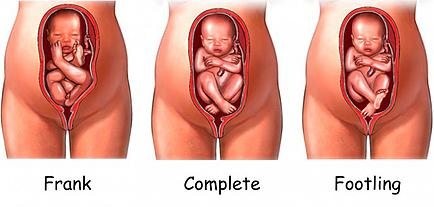

Breech

A breech position means the baby presents bottom or feet first, rather than head first.

During pregnancy, many babies are in the breech position. However, most babies turn before 37 weeks.

If your baby is still breech at 37 weeks, the chances of your baby turning by itself are low.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the implications of this for your birth plan and what options are available.

Your options may include:

- external cephalic version

- vaginal breech birth

- elective caesarean birth (usually performed after 39 weeks).

Breech vaginal birth

You may be suitable for a vaginal breech birth if:

- you go into spontaneous labour

- the estimated weight of your baby is within normal limits

- your baby is in either a complete (flexed) or frank (extended) breech presentation

- an ultrasound scan confirms your baby’s head is not extended

- the size and shape or your pelvis are adequate

- you have no pre-existing complications in your pregnancy.

Types of breech presentations

More information: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Breech presentation at the end of your pregnancy

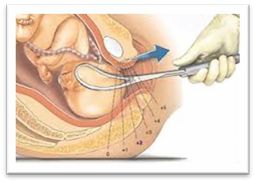

External cephalic version (ECV) for breech presentation

ECV is a commonly practiced procedure with a low risk of complications.

ECV can reduce the need for a caesarean birth. The success rate is approximately 40% for first time mothers and 60% for others. If you choose to have an ECV, the procedure is done in hospital.

- A trained doctor gently turns the baby by placing their hands on your abdomen and gently coaxing the baby around so it can be born head first.

- This procedure is done at around 37 weeks, using ultrasound to help see the baby, cord and placenta.

What you need to know

Mother and baby are monitored during the procedure.

There’s a small risk that turning the baby may tangle the cord or separate the placenta from the uterus – in which case an emergency caesarean birth is needed. If the baby is still in the breech position at the end of pregnancy, a caesarean birth may be recommended.

More information:

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – External cephalic version (ECV)

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) – Breech presentation at the end of your pregnancy

-

What if my pregnancy is ‘overdue’?

Note: treat ‘home remedies’ with a dose of caution.

A simple internet search will give you countless results for ‘natural’ ways to trigger labour. Be sure to get your midwife or doctor’s OK before trying any home remedies, herbal supplements or alternative treatments.

Around 80% of babies are born between 38 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. This is often called ‘at term’. Babies born after 40 weeks are described as ‘post term’.

It's OK to feel frustrated or disappointed if your pregnancy has gone past its due date. Try not to worry, soon you'll hold your baby in your arms and the long wait will be over.

While you are waiting, stay in touch with your midwife or doctor. You'll need frequent check-ups until your baby is born.

Take advantage of the extra time. You may want to:

- get some extra sleep

- make any final preparations for baby

- stock your freezer with meals

- review your birth preferences.

Overdue pregnancy

If your labour hasn’t started by 41 weeks, your midwife or doctor will probably offer you a 'membrane sweep’.

What is a membrane sweep?

A membrane sweep involves a vaginal (internal) examination that stimulates the cervix (neck of your womb) to produce hormones that may trigger natural labour.

If your labour still doesn’t start naturally after this, your midwife or doctor will discuss with you a date to have your labour induced.

If your pregnancy lasts longer than 42 weeks there is a higher risk of complications.

Your doctor or midwife will probably recommend regular tests to check on your health and your baby’s health. After 42 weeks, there is a higher risk of stillbirth or fetal compromise.

These tests might include an ultrasound to check the amniotic fluid index and an ultrasound to check the biophysical profile.

More information: Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Overdue

-

How will my baby’s heart rate be monitored during my labour?

Intermittent monitoring

If you have had a healthy pregnancy and there are no problems at the onset of labour, your midwife will listen to your baby's heart beat every 15 to 30 minutes using a small hand-held Doppler ultrasound device.

Continuous electronic monitoring

If you or your baby have any known risk factors, continuous monitoring may be recommended.

This is done using a CTG (cardiotocograph) machine. This type of monitoring is external (outside your abdomen).

Telemetry

Telemetry is a wireless system of monitoring that can be used while you are mobile and walking around, even in the shower.

Fetal scalp electrode (FSE)

Sometimes it is necessary to attach the monitor directly onto your baby via a special lead. This is called a fetal scalp electrode. The lead is placed on your baby’s head during an internal vaginal examination. Telemetry (wireless) monitoring is still available using an FSE.

This type of monitoring is internal and is more reliable and accurate than external monitoring, particularly when you are mobile.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

-

Concerns for baby in labour

When immediate birth is required

If there are concerns for baby’s wellbeing and immediate birth is required, baby will be birthed as soon as possible with vacuum or forceps (or perhaps by caesarean birth).

A change in the baby’s heartbeat can be a sign the baby isn’t getting enough oxygen. This is called ‘fetal distress’.

Signs of fetal distress include:

- a faster, slower or unusual pattern to the baby’s heartbeat

- a bowel movement by the baby seen as a greenish black fluid called ‘meconium’.

If these signs are present, your doctor or midwife will discuss with you, your continued management and care during your labour.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Fetal monitoring in labour

Why is meconium a concern?

Meconium aspiration syndrome

Meconium aspiration syndrome is when a baby inhales the meconium before, during or after labour.

It can cause respiratory problems as serious as pneumonia, and although it rarely happens, it can be fatal.

Meconium stained fluid occurs with about 10% of babies who are 'term' (37 to 42 weeks).

The presence of meconium during labour can be (but not always) a sign that the baby is becoming distressed.

Your labour will be observed closely and a paediatrician will be available at the birth, in case specialised care is required.

-

Antibiotic treatment during labour

Antibiotic treatment during labour may be recommended for:

- preterm labour – if you are in preterm labour, it may be caused by an infection

- PROM (Prolonged Rupture of Membranes) – to prevent a uterine infection

- Group B Strep infection

- having a fever during labour

- a preventative – in some situations, you may be given antibiotics as a preventative measure against potential infection, an example might be for a caesarean birth.

What is a Group B Strep (GBS) infection?

Approximately 15–25% of women are carriers of Group B Streptococcus, without any symptoms. Usually, you do not know you are a carrier.

It is usually detected by a vaginal swab. GBS can come and go during your pregnancy. If it is present when you give birth, there is a chance your baby can become infected.

If you are known to be GBS positive, and you have additional risk factors (e.g. your waters have broken and are therefore no longer providing a protective barrier for your baby), you will be offered antibiotics to try to prevent an infection in your baby.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy

-

Blood loss after birth

Is it normal to bleed after birth?

Yes, bleeding in the days or weeks after birth (also called lochia) is completely normal and occurs regardless of whether you have a vaginal or caesarean birth.

How much bleeding is considered ‘normal’?

Women’s experiences of bleeding after birth vary considerably. In the first few days after birth, the majority of women experience moderate to heavy bleeding, however some experience minimal bleeding. This early bleeding is usually more red in colour.

Over the next few days to weeks, this bleeding will gradually decrease and will change colour. Women describe their blood loss to be browny-red, pinky-red, pale pink or a creamy colour.

The majority of women will stop bleeding between four and six weeks, however some women experience bleeding for longer than this. It is also common for bleeding to be heavier after breastfeeding.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Abnormal blood loss

How much bleeding is too much?

- if you have a sudden and continued increase in your blood loss

- if the blood suddenly changes in colour to a brighter red

- if you are experiencing heavy blood loss and are feeling dizzy, weak, sweaty, pale, have a fast heartbeat or rapid pulse

- if your vaginal discharge is offensive (smelly) – this may indicate infection.

Every woman is different, however, as a general guide – if it has been more than 24 hours since birth and you are soaking more than one maxi-pad every two hours, you may be bleeding too much. If this is happening - call your doctor, midwife or 13HEALTH (13 43 25 84).

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Bleeding after birth

Next section: Induction of labour and augmentation

-

Induction of labour and augmentation

-

Why are inductions needed?

Induction of labour (IOL) is a relatively common procedure.

The IOL rate in Queensland is about 22%.

IOL is a procedure used to stimulate contractions, before labour begins on its own. It includes the use of medication or other methods to bring on (induce) labour.

The reasons that an induction could be recommended include:

- your pregnancy is overdue

- multiple pregnancy

- your baby is small for their age

- your membranes have ruptured (waters have broken) and labour has not started

- certain medical conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure or cholestasis.

Your doctor or midwife will discuss the reason for your induction at your antenatal visit.

More information: Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

-

Frequently asked questions – inductions

What is a Bishop score?

It is a score used by doctors and midwives to determine how ‘ready’ your cervix is for labour. It is a combination of how soft, open and thin your cervix is, and where your baby is positioned in your pelvis. The score assists in deciding which method of induction will be most successful for you.

What is ‘cervical ripening’?

Ripening the cervix is a process that helps the cervix soften and thin out in preparation for labour. Medications or devices may be used to soften the cervix so it will stretch (dilate) for labour.

How will I be induced?

The method of induction will depend on:

- the condition of your baby

- your condition

- the progress of labour

- dilation of the cervix

- how far down in your pelvis the baby has gone

- the position of the baby's head

- your comfort and choice.

- Transcervical catheter ‘balloon catheter’.

- Prostaglandins, a ‘gel’ or pessary (Cervidil).

- Artificial Rupture of Membranes (ARM) ‘breaking your waters’.

- Syntocinon (oxytocin), sometimes called ‘the drip’.

What are some of the different methods of induction?

How long do inductions take?

There are lots of factors involved. Some women go into labour and deliver within a few hours after induction. Others take one or two days to start labour.

-

Questions to ask about induction of labour

Your midwife or doctor should discuss the pros and cons of any intervention so you can make an informed decision.

You should ask your doctor or midwife whether induction will:

- hurt?

- affect my recovery?

- affect my ability to breastfeed?

- affect any future pregnancies?

You should also ask questions such as:

- why would I need this intervention?

- what are the risks and benefits to me and my baby?

- are there any alternatives?

- is it likely to increase my need for more interventions?

- can I do anything while I’m pregnant to decrease my chances of needing the intervention?

- what is the hospital’s policy on this intervention and the evidence to support this?

More information:

- Queensland Clinical Guidelines parent information – Induction of labour

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby – Induced labour

-

Methods of induction

Balloon catheter

A cervical ripening balloon catheter

This is a thin tube or catheter with balloons on the end. The catheter is inserted into your cervix and the balloons are inflated with saline (salty water).

Once inflated, the balloons apply pressure to the cervix. The pressure should soften and open your cervix.