Robert O’Connor

It is no wonder that Vietnam Veteran Robert O’Connor became a novelist inspired by his own action-packed war service which has provided an abundance of material for a series of books.

Originally posted to 1 Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers (RAE), in a building construction role he obtained a transfer to a field (combat) troop only to find himself, on his first mission, hanging out of a helicopter after being extracted from a Long Hai mountain top escaping a sizable enemy force.

The Battle of Coral-Balmoral veteran was only prevented from falling the 500 metres to the ground because he had straddled a mullion, a vertical ‘bracket’ on the edge of the cargo bay.

“I likened this altitude to the height of Mt Tamborine but at no time did I feel I was in danger of falling or more accurately, letting go of the mullion,’’ he said. “I’m convinced it saved my life…as well as divine intervention.’’

Mr O’Connor, 78, of Woolmar near Kilcoy, was drafted into Vietnam in 1966 before he had the chance to enlist himself, which was his aim after finishing his five-year carpentry and joinery apprenticeship.

When Mr O’Connor came home from Vietnam he returned to the building industry but for the past decade he has focused on his passion for writing novels, inspired by his own war experiences, about young Nasho (national service) tunnel rat Bob Sten, in a series titled, ‘The Conscript Diaries,’.

Mr O’Connor was the sole engineering representative supporting an infantry section on a reconnaissance patrol in the Long Hai Hills which was home to two enemy battalions of frontline fighters based in the Minh Dam Secret Zone, known for a vast cave network, rocky landscape, hidden mines and boobytraps.

“We were halfway up the mountain when the mood changed, you could sense it in the air,’’ Mr O’Connor said. “A short time later, just before we reached the top of the mountain, we came under heavy fire from the Vietcong.

“We pressed ourselves to the ground, taking what cover we could behind rocks and trees. The firefight lasted for about three hours, with bullets and rockets zapping a foot or two over our heads,’’ he said. “We stayed that way until a chopper managed to find room between the trees to get low enough for us to clamber aboard.”

Mr O’Connor, with his 30 plus kg pack including TNT and ammo, was the last to board the chopper.

“By the time I got to the chopper the others were strapped into the seats at the rear of the cargo bay with their packs on the floor. There was only one floor space available.

“The sprint to the chopper was the fastest I’d moved in my life.

“Once we had forward momentum, the pilot flew us up high again, to mountain top level, and once more in the sights of the Vietcong. So, we went vertical because you can’t fly straight when you’re getting shot at. With the force of the chopper, I fell out and bumped up against the mullion and I grabbed it.

“I was not only outside. I was also vertical, upside down, being buffeted violently against the fuselage of the chopper with the packs of the safely-strapped-in infantry diggers banging into me on their way out the ‘door’.

“Those five years in the building industry stood me in good stead because I’d developed strength and there was no way I was going to let go of that beautiful mullion. I was outside the chopper, somewhere around a minute, after which I managed to partly climb and partly be dragged back on board.’’

On arrival back at Kangaroo pad, the helicopter landing zone at Nui Dat and seeing the bullet holes in the helicopter, Mr O’Connor realised how lucky he was to walk away unscathed. He has since tried to track down the men who were in the helicopter with him during the heart-pounding experience, both Infantry and RAAF, but to no avail, despite several advertisements in the Vetaffairs newsletter and the RSL magazine.

In May 1968, Mr O’Connor was sent to the Battle of Coral-Balmoral where he served on the frontline for three-and-a-half weeks, in both the first and second attacks. There were 25 Australian soldiers killed and Mr O’Connor endured several close calls.

“We were attacked several times by large forces of Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army regulars,’’ he said. “We were generally attacked about midnight, and they would disengage just before sunup.

“I spent four nights on the eastern perimeter which was the target for most of the attacks. On that front enemy soldiers attacked us across open ground.

“We, tunnel rats, would go out after the battles and check the ground for mines and the bodies for booby traps. You had to be careful where you walked out there on the battlefield because you could be seen for hundreds of metres. Initially I would crouch down to lower my profile, wondering if I was in the crosshairs of a sniper’s telescope but after a short time I realised how futile this was and simply did my job hoping for the best.’’

On several occasions during battle fire enemy mortar fire landed within six metres of our firepit. “We’re going to die tonight,’’ said my companion.

For the most part Mr O’Connor, who turned 23 during the three-and-a-half-week battle, was on the western perimeter as part of a three-man listening-machine gun post.

Following one night of an intense and prolonged firefight, their protective sheeting (hoochie) was peppered with shrapnel holes, yet we didn’t get a scratch.

“Maybe, divine intervention?,’’ he said.

Mr O’Connor said the battlefield revealed unfathomably graphic scenes displaying the full horrors of war as the dismembered and shattered remains of fallen soldiers were there and which were always treated with respect and dignity.

One time he saw movement near a small bush on the artillery-scarred battleground. “It was a blue-banded krait curled up in what was left of the shrub, it didn’t worry about me, he didn’t see me as a threat after such night action. “Hello mate, you’ve been through the battle too.’’

One evening at dusk Mr O’Connor went to relieve himself and less than 20m away he saw an enemy soldier emerge from tall grass and do the same thing.

“I stopped still but then he saw me, and we both put our thumbs up and he disappeared back into the grass,’’ he said.

As a member of 2 Troop, 1 Field Squadron RAE, he was also known as a tunnel rat. In five months, he descended twice into underground tunnels, with many just over two feet (60cm) high. Both times were testing experiences, and he has since suffered from bouts of claustrophobia.

“My job was to crawl down tunnels, so every time you went down a tunnel you had a 33 percent chance of being killed or injured. Tunnels are terrifying things because you’re unaware of what is down there. It’s pitch black, you are carrying a handgun 38, and an army torch which was notoriously unreliable.

“The bloody things would go out without warning.”

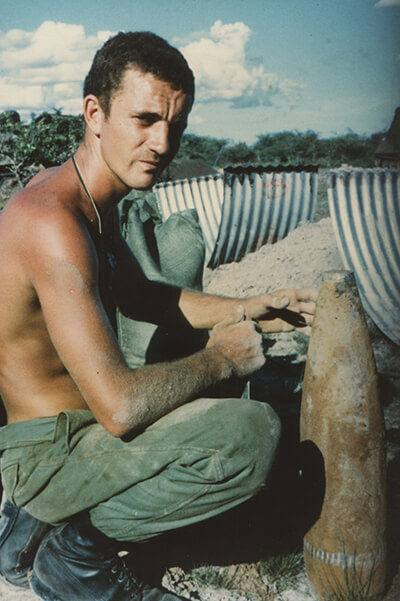

“The most hair-raising though is dealing with unexploded munitions such as mines, artillery shells or mortar ‘bombs’. If an explosive device is booby trapped with a pressure release switch you only need to move it, release the pressure on the switch by two millimetres for the device to detonate.

“You needed resilience. Other frightening things one could encounter in tunnels included natural dangers such as poisonous snakes and huge trap door spiders.’’

His time in Vietnam was a long way from Mr O’Connor’s childhood growing up at Wavell Heights, as the youngest of three, with an older brother and a sister.

His adventurous spirit was developed early as he would spend his weekends climbing trees and cliffs, swimming in creeks and swinging on ropes over streams, or riding his bike for miles around Brisbane’s outer (in those days) northern suburbs.

After school he served a five-year apprenticeship in carpentry and joinery.

“Then out of the blue, shortly after completing my apprenticeship I received a letter and was given eight days to present myself to Enoggera Barracks and from that point my life changed forever,’’ he said.

He was sent to Singleton, in New South Wales, for three months of recruit training and then did another three months Corps training in the Corps of Engineering at Casula, NSW.

In Vietnam he lived in tents at Nui Dat, the Australian Task Force base. He said the pine floors would be half-rotten because they would be so damaged because of the constant humidity and monsoonal rain of the wet season.

“I was happy about being in South Vietnam, being given the opportunity to do something for my country, I found the business of war exciting. Something I could only imagine came to stark reality. To say it was character building is understating its impact and the effect it has on one’s psyche,’’ he said.

One memorable experience, where Mr O’Connor demonstrated humanity in the face of the inhumanity of war, was when he helped a crippled Vietnamese man, with a young family, who was too afraid to receive treatment during an Australian medical team’s visit to a village.

“He had a disfiguring medical condition, leprosy I was told later, and was struggling with crudely made crutches fashioned from tree branches,’’ he said.

“I walked up to the family and all the villagers went quiet because all of us diggers were armed to the teeth.

“I knelt on one knee next to this little girl, no doubt the daughter of the crippled man, and looked directly into her eyes, making a human connection.

“I led the family to the medical staff, who attended to him. Later in the day, when the village search was completed, the girl and her family thanked me which had a huge emotional effect on me.’’

Following the Battle of Coral-Balmoral he took his requisite six-day R & R break and chose to go to Taipei, in Taiwan. He enjoyed the sightseeing in Taipei and befriended a family who invited him to dinner.

“There was about 30 family members there, it was a sumptuous meal, such an authentic (Chinese) experience,’’ he said. “They thought I was an American GI but then I explained I was an Australian by pointing to a map of the world hanging on a wall. A collective ‘Ahhh sooo!’ was the response.’’

After a ten-month deployment, Mr O’Connor returned to Australia as a more mature person. “I felt I’d taken a quantum leap in my understanding of the world I’d left. Of my perception of my fellow man and woman,’’ he said.

On returning to Australia, he also found many people, including his own family, did not understand what was happening in Vietnam and the experiences Australian soldiers were facing.

“I arrived in Sydney around 11pm and spent the night on a wooden bench with my kit as I had to organise and pay for my own fare back to Brisbane, which was as I recall $17. My brother picked me up from Brisbane’s Eagle Farm Airport the next day. ‘You’re coming to work for me.’ He had a building business - that’s how it was,’’ he said.

“It was hard to go back to normal life. I didn’t have time to process my experiences. I went back home to sleep on a couch in the loungeroom, my previous bedroom and bed had been taken by another family member, but it was paradise after living in rain-soaked holes and dripping rainforests or waking up in my mouldy canvas tent we shared with a huge cobra that lived under the floorboards.

“I could go to a cold fridge and pull out a glass of real milk or some cold roast chicken. It was sheer bliss.’’

Within 18 months Mr O’Connor had started his own building business but he said general society and governments treated veterans like himself “in a shoddy way’’.

“Like one of our neighbours who lived directly across from us. Several days after arriving home I walked past her place as she was hosing her garden. Whereupon she dropped the hose nozzle, turned her back on me, walked back into her house and shut the door. We (veterans) were like pariahs. I remember in 1969 being asked to leave a RSL club. We were treated shamefully for decades but things have improved out of sight in the past decade or so.’’

He said growing up in the post-World War II era he was in awe of the military but he changed his mind following his war experience.

“The commanders I came into close contact with did not impress me, however I did meet some nice blokes, regular diggers, whom I fought beside,’’ he said.

Mr O’Connor returned to Vietnam in 2016 on a Tunnel Rats tour with some of the men he served with, but he said the entire area was now unrecognisable. It was difficult to answer what Vietnam Veterans’ Day meant to him.

“I have mixed emotions and feelings,’’ he said. “I have pride in the jobs we did over there and overall, I have mainly positive memories from Vietnam.

“It’s the excitement that only war can bring. The adrenaline-pumping, danger, the sounds, smells, and sights – I felt alive. I had a purpose and that was serving my country, and I was doing my part. Another fortunate result of my army service was it gave me the wherewithal to later become a writer.’’

Interested readers may obtain more information about Mr O’Connor’s series of books on: www.bobsten.com.