Rodney Slater

Vietnam Veteran Mr Rodney Slater felt destined to serve Australia in the army as he grew up playing in bushland near the Enoggera Barracks.

With an older brother, John, and four cousins living next door, Mr Slater was never short of mates when playing soldiers in his favourite game of waries.

“I grew up in Mitchelton but at the back of our house was bush and less than a kilometre away was the army camp at Enoggera, now the Gallipoli Barracks,’’ Mr Slater says.

“We would play up near the barracks, build humpies, catch possums, play sling shots, and shoot birds. I grew up playing cowboys and indians and playing soldiers in waries.

“Serving Australia in the army was something I always wanted to do.’’

Mr Slater, now 73, and living at Sandstone Point, would ultimately serve 26 years in the army, rising to a Warrant Officer Class One (WO1) before taking a discharge in 1993.

Throughout his service he and his wife of more than 50 years Julie, raised two children, Rachel-Anne, 51, and Shane, 50.

Mr Slater loved “military life’’ including his time in Vietnam.

“It was the whole thing, the teamwork, mateship, looking out for each other, being the best you can be, the discipline, the organisation, aspiring to high personal standards, to always do the best you can, in whatever you are doing,’’ he said.

“Being in the army is more than a job, it becomes a way of life.’’

Mr Slater was 17 years old when he enlisted. Seven days after he turned 19 he left for Vietnam where he served as a private and lance corporal in the assault pioneer platoon.

He’s grateful to have survived several “close calls’’ during his year-long deployment in 1968 and 1969. He respectfully spoke about his fallen and injured comrades who like Mr Slater, regularly and bravely put their lives on the line as part of their dedication.

Mr Slater does not know whether it was the fact he was born on a Melbourne Cup day, in a year where the horse Foxzami won, but he experienced several “lucky days’’.

One day forever etched into his memory was when he was asked by his platoon sergeant to jump off a vehicle to take up the role of signaler on a stretch of track outside Dat Do, near Nui Dat in July 1969.

“One of the trucks in our battalion was blown up and I was fortunate not to be in it,’’ Mr Slater said. “I was on this truck with my section when the platoon sergeant told me to hop off and be the signaler for the day.

“Only about 500m down the road the truck was blown up and all but one of the men in the truck was wounded. Three of the men were medivaced back to Australia while others had some slight shrapnel wounds.’’

Another “close call’’ was when Mr Slater had just turned 20, on one of his final days in Vietnam, in November 1969.

“We were out doing land clearing, there were bulldozers dragging a big chain clearing a great swathe of land to make it difficult for the enemy to move about in daylight hours,’’ Mr Slater said.

Mr Slater was in an armed personnel carrier (APC), as part of the protection party for the bulldozers when they came under attack.

“We were fired at by a rocket but fortunately it hit the branch of a nearby tree and exploded. We heard the bang and saw the tail fin sitting about two metres from us,’’ he said.

“It had gone off, but if it had hit the side of our APC instead, who knows how much damage it could cause but if it hits something flat and hard like an APC, it explodes…it inverts and burns through the armour.

“We will never know if we would have all died but it was a close call and something you don’t dwell on.’’

Mr Slater relished the responsibility of serving in Vietnam but said you could never relax because of being on a constant alert of an attack.

His early calling to serve in the army was fostered by growing up hearing stories about his uncle’s service in World War II, and reading books about the war. He also took part in cadets at Mitchelton State High.

“At school cadets we were taught how to shoot for real, practiced tactics, bushcraft and navigation,’’ Mr Slater said. “I liked the idea of serving my country, doing something for someone else, giving back to my country.

“It was also the excitement of it, to travel overseas, and maybe go to war. You don’t join the defence force if you are not prepared to go to war.’’

Before enlisting Mr Slater had to talk around his mum who took several months of convincing. He enlisted in 1967, when he was 17 and a half years old.

“I finally convinced my mum, but my dad was always okay with it. I think my mum always regretted giving permission for me to go off to war,’’ he said.

On enlisting, Mr Slater was first sent to recruit training at Kapooka, outside of Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, and then to specialist infantry training at Ingleburn, Sydney.

After Sydney, Mr Slater was posted to the 9th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (9 RAR). It was a new infantry battalion raised at Woodside, just outside Adelaide.

From November 1967 he took part in “very intense’’ 12 months of training including the assault pioneer course.

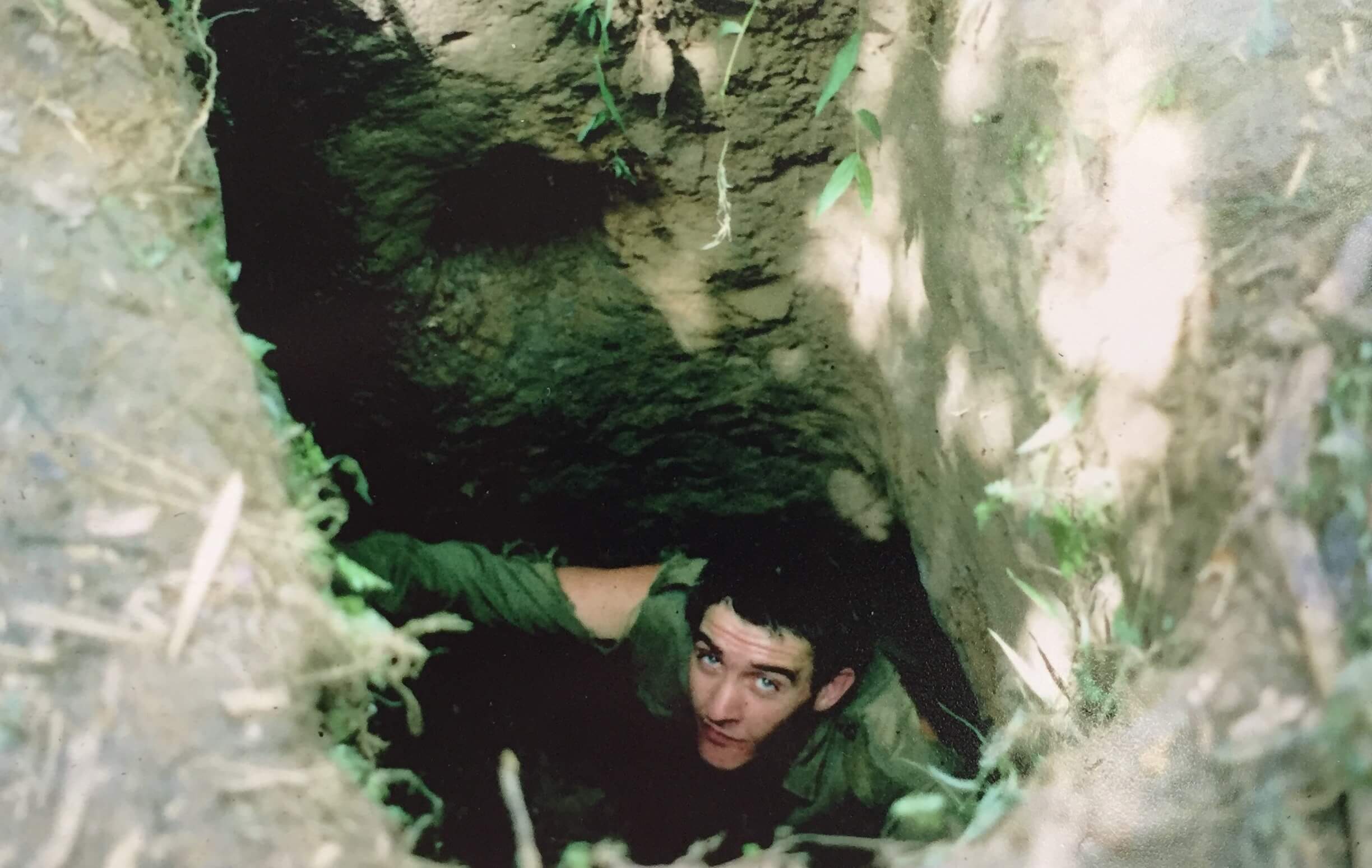

“The assault pioneer course required us to dig holes, field defenses, land mine and booby trap clearance, and the use of explosives to destroy enemy installations,’’ Mr Slater said.

Mr Slater said the assault pioneers were infantry engineers whose duties included digging in command posts, putting up barb wire and replacements, blowing up bunkers and old ammunition and going out on patrol in several provinces.

Following the year of training he was on the boat HMAS Sydney bound for Vietnam and was part of his regiment’s on-board first birthday celebrations.

“We trained as a battalion, and we went over there as a battalion,’’ he said. “It was all a great big adventure. I hadn’t been overseas before.’’

He said everyone bonded as a battalion and was part of the “team even though there was a lot of ribbing between nashos (national service) and regs (regular army)’’.

Mr Slater said his battalion arrived at the port of Vung Tau, which was “hot and smelly’’, before transferring to the Australian Task Force base at Nui Dat.

He said Nui Dat accommodation consisted of a series of “big old canvas tents, 14 feet by 14 feet’’, with two to three soldiers sharing a tent.

“Nui Dat had sandbag walls which were blast walls. There were proper beds with a mattress, sheets, pillows, our own mozzie nets, steel lockers,’’ he said.

“Each tent had a trench dug for protection and there were duck boards on the ground. Not a dirt floor but timber floors raised off the ground. In the wet season, it was monsoonal, and rain would bucket down onto the red dirt, and it would get very muddy underfoot.’’

When out on patrol Mr Slater said soldiers carried half-shelters called “hoochies’’ which clipped onto another half-shelter which could then be shared by two soldiers.

“Often we didn’t worry and just slept on the ground with no pillows but would put our head on our packs,’’ he said.

Mr Slater said the most difficult challenge was staying awake for night patrols especially when looking for mines and booby traps which were often found in a patterned network.

“Our biggest fear was stepping on mines and booby traps especially because we were only working with rudimentary mine and metal detectors. All the training we did at home paid off. We found a lot of the areas were bombed so a lot of shrapnel made it difficult using a mine detector therefore a lot of clearance was done by hand.

“The biggest challenge was staying awake at night especially when you were out and about in the bush doing an ambush or out patrolling or doing a piquet. You would take turns manning the machine gun.

“It would be pouring rain and you can’t move. It would be a little bit tense when searching for mines and booby traps, you couldn’t let that get into your head at all, you had to do what you had to do.’’

“At one stage we found hundreds of mines and booby traps because we identified the pattern with how the Vietcong were laying them.’’

Slater’s battalion also worked with the Vietnamese national police to help facilitate searches of villages for Vietcong members. The Australians provided protection for the police when acting on intelligence that Vietcong were hiding at a particular village.

“Some villagers had family members in the Vietcong so we would cordon off huts and search. One of our soldiers found a Vietcong hiding in a big wicker basket in the village, in one of the huts, after he noticed a rifle barrel sticking out, so he let rip,’’ Mr Slater said.

Mr Slater was injured in late 1968 when he fell into an empty grave on a night patrol during a mission of cordoning off and searching a village.

“The grave was deep, a long way down, the ground swallowed me up. It was pitch black. I wasn’t walking directly behind the person in front of me, like I should have been. I returned from that operation with a badly sprained ankle.’’

Mr Slater had a couple of stints of rest and recuperation at Vung Tau – away for two nights and a day from Nui Dat.

“The recreation centre was at the Australian Logistics Base at Vung Tau. It was good to have a break from carrying our weapons around,’’ he said. “We would go into town, mostly visiting bars and street stalls but there was a curfew.’’

Mr Slater also enjoyed a five days and six nights break in Hong Kong where I “did the touristy things, found some good bars and restaurants’’.

Once his year of Vietnam War service finished in November, Mr Slater flew home for three-month leave with an eight-hour direct QANTAS flight to Sydney.

“On the first night.. it was good to be back in Australia,’’ he said.

Mr Slater returned home to Brisbane the next day and went for a night out in the city with a cousin.

“It was surreal. it didn’t feel normal walking around Brisbane,’’ he said. “People asked what I did for a living, and I would tell them I was a soldier and had just come back from Vietnam.’’

Despite a lack of understanding by many people about Australia’s involvement in Vietnam, Mr Slater has mainly positive memories from Vietnam.

He has since become the unofficial keeper of his platoon’s records and an editor of an occasional newsletter.

He has attended several reunions and meets every month with fellow infantry people as part of the Rifleman’s Lunch at Mooloolaba Surf Club, on the Sunshine Coast.

One member of the Rifleman’s Lunch club was Major Harry Smith, who commanded Delta Company 6RAR at Long Tan in 1966. He only stopped coming to the lunch club earlier this year when he became too frail before he passed away in August at the age of 90. Major Smith was depicted by Australian actor Travis Fimmel in the 2019 film Danger Close about the Battle of Long Tan.

After his discharge from the army, Mr Slater gained employment with the Corps of Commissionaires in Brisbane, as well as a Casual Court Officer with the Federal Court of Australia, Brisbane Registry.

He later became the Senior Court Officer at the Federal Court, then due to medical advice resigned and retired in 2003.

Mr Slater has come to appreciate Vietnam Veterans’ Day “as a chance to get together with my mates especially as it’s a tri-service day for the Navy, Army and Airforce’’.

He has wanted to return to Vietnam but only with men who he served with but unfortunately most of his friends have not shown the same interest to return.

“In Vietnam it became about the bonds you built with each other, the camaraderie,’’ Mr Slater said. “None of us were perfect, we all had our strengths and weaknesses, but we all got on for the good of the team, through the highs and lows.

“The experience of Vietnam has only strengthened our friendships and we all still stay in touch. The mateship and camaraderie developed during our service lives forever.’’