Shorebirds

Living between the tides

In a little over 24 hours the coastline goes through a tidal cycle from one high tide to the next. Between high tides, the water is pulled away by the gravitational force of the moon, revealing a new environment and with it a new community of animals and plants. Where the slope of the land is gentle and the coastline is protected from high energy wave action, these intertidal and foreshore areas take the form of vast mudflats and sandbanks. As the tide goes out each breaking wave dumps or disturbs sediment and the organic matter that feeds the multitude of crustaceans, worms and molluscs living in these intertidal areas. Specially adapted birds soon move in to feed on these small animals until the returning high tide forces them to find a roost and wait for the next low tide.

These birds are the shorebirds or waders. Probing and pecking, flipping rocks, and prising open shells as they search for food. Many of these shorebirds are migratory, flying between Australia and their breeding grounds in the Arctic Circle—a 20,000 kilometre round trip.

Of the more than 50 shorebird species most regularly observed in Australia, about a third are considered resident species and the remainder are migrants. These migratory shorebirds spend each summer in Australia feeding and readying themselves for the flight to the Arctic Circle for the breeding season. They range in size from the red-necked stint weighing less than 30 grams up to the eastern curlew which can weigh a kilogram.

‘A gesture of ancient faith and present courage’

Migration has been described as a ‘gesture of ancient faith and present courage’ and the preparation and timing of this journey by millions of shorebirds is critical. Each year this faith and courage are tested as these birds follow their ‘flyway’, relying on traditional stopover areas to feed and rest; passing through as many as 22 countries before reaching their breeding grounds. Even a short delay in their migration could jeopardise their breeding success, as their arrival in the Arctic is timed to coincide with the brief emergence of clouds of small flies that the birds gorge themselves on and feed to their young. And there are many risks along the way.

Like Australia, many of these countries are signatories to international agreements to protect these flyways. However, each year more overseas wetland habitat is lost to development along the flyways reducing the sites available for the birds to feed and rest as they continue northward. Without enough sites some shorebirds are unable to complete their migration. Populations of many waders are now in decline and a number of species are classed as threatened.

Destination Queensland

For many shorebirds, Queensland is the favoured destination for the Australian summer months and the starting point for their long autumn journey back to the northern hemisphere. Their time here is spent feeding and readying themselves for the return flight.

In Queensland all shorebirds are protected, and its coastline provides them extensive areas of tidal mudflat and sand bank habitat. Many of these areas are protected within state and commonwealth marine parks or are listed as internationally significant wetlands under the Ramsar convention.

Even so, shorebirds still face significant threats—particularly where coastal areas are near large human populations and where people use these areas for recreation and exercise, and to walk their dogs. The main threat is human disturbance, albeit often unintentional, with many people surprised to find that their actions can have impacts on the ability of shorebirds to find sufficient food, to migrate and ultimately even their breeding success.

Accidentally startling a group of shorebirds into flight when they are feeding in the intertidal zone may seems harmless enough. But if those birds have already been disturbed that day by the people walking by and more people will walk by later on, they may lose much of their limited available feeding time – and if this happens day after day, it will restrict their ability to build up sufficient energy reserves to fuel their journey to the northern hemisphere in the Australian autumn.

What can shorebirds teach us about how to use space?

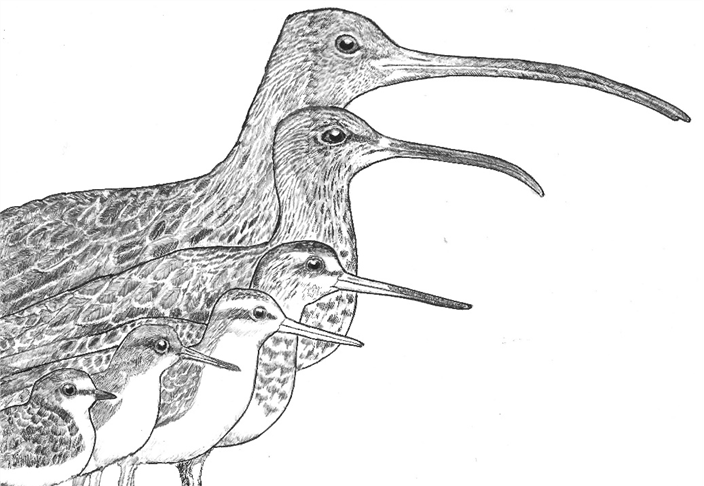

Shorebirds can mass together in their tens of thousands on a tidal mudflat, concentrating along the water’s edge on an outgoing tide where their food is most abundant. Under these conditions they rarely waste time fighting over space or food. Competing for food and defending a territory (or avoiding the territory of others) takes time and energy away from feeding, migrating and ultimately breeding. Shorebirds avoid this problem by being able to feed at different depths (an eastern curlew has a bill 180mm long while a small plover with a bill less than 10mm long will run and peck at small crabs and worms on the surface.

If you spend some time watching shorebirds, a picture may start to emerge showing how each type of animal coexists by having its own space (or depth) at which it feeds. This allows birds of different species to focus on what’s in the mud or sand they are standing on and disregard, or at least tolerate, the large number of other birds that surround them. This coexistence through avoiding competition is a strategy that many animals and plants use in the nutrient-rich intertidal zone. Over time, animals become specialists feeding on a part of a common food resource that no other animal uses. Feeding in different locations or at different times are common ways of avoiding competition. For shorebirds it is feeding at different depths and this has resulted in an ecological community with an amazing diversity and abundance of living things. Take some time to watch this phenomenon at work next time you see a feeding assemblage of shorebirds.

People and dogs

Into this ecological matrix walk (and run) people and their dogs. While mudflats and sandbanks attract people because of their openness and flat and soft surface for walking, it is the vibrant community of animals just below the surface that draws in the shorebirds.

The shorebirds move into the areas where these animals are most abundant and their presence and level of activity reveal an extra dimension to an intertidal area. By being aware of how a mudflat works below the surface you can better understand that an expanse of mudflat or sandbank only appears to have a sameness about it. The shorebirds mark the locations that are the best places to feed. This is where they need to be, while we only need somewhere flat and not too wet for walking.

Walk lightly in the tide zone and leave the shorebirds alone

Instead of walking on the mudflat you can now start walking in it using your understanding of how it works (think about what’s happening in the mud you step into and what’s living in it; accept that the shorebirds need to be where they can find food and give them space).

Here are a few practical tips for walking lightly in the tidal zone:

- Before you step ‘into’ a mudflat or sandbank where there are shorebirds, look at where they are feeding and avoid the birds and the feeding areas as much as possible.

- Visit tidal areas when the tide is at its lowest and keep away from the tide line. This gives the birds and you space to spread out and avoid each other.

- Never walk through a shorebird roost at high tide. This is where the birds rest safely and wait for the next low tide. It is where they are most vulnerable, particularly on spring high tides when they are clustered together in greater densities.

- If you get too close to a shorebird and it flies away, remember to stay further away next time.

- Remember that you won’ t be the only person walking through an intertidal area. Others have come before you and more will come after you. If everyone disturbs the waders when they are feeding, the cumulative effect over time could stop them from breeding.

- Dogs should be kept on a lead. This is a legal requirement in many areas. If your dog needs lots of exercise check if you have an off-leash dog park nearby.

Remember, you have a choice where you walk when you visit shorebird feeding sites. Shorebirds need to be where they can find food. Give them room to feed and let them prepare for the long journey north. Your consideration combined with their ‘ancient faith and present courage’ will help them get there.