Monitoring and management

The management of northern hairy-nosed wombats in Queensland is undertaken by the Department of Environment, Science and Innovation (the department).

It has four broad aims:

- establishing additional populations in areas geographically distant from current populations

- supporting research to improve our understanding of northern hairy-nosed wombat life history and biology

- conserving habitat suitable for sustaining northern hairy-nosed wombat populations

- monitoring existing populations to inform on-ground management and recovery actions.

Research programs

Field research on the northern hairy-nosed wombats first began at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) in the 1970s when staff from Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service monitored burrow activity and distribution in the park. They found that burrows were restricted to areas of deep sandy soils, along the banks of a dry, ancient watercourse, and estimated the population to contain as few as 20 to 30 wombats.

In the 1980s, there was a major trapping study of the wombat population, which found evidence that wombat survival had increased after 1982, when cattle were excluded from the area. By 1986, ongoing research estimated the population had increased to approximately 70 and provided greater insight into the population’s breeding and age-structure. This was followed by a trapping and radio-tracking study that indicated wombat’s home ranges were small and centrally located around established burrows. This study also found seasonal variation in home range size, with wombats foraging over larger areas in winter when food resources were scarcer.

The next trapping studies, in the early 1990s, revealed there had been no increase in the population. This was thought to be due to the major drought in central Queensland at the time. Of concern, was the increasing age of the population and the low number of females. By 1999, normal rainfall had returned, with abundance estimates indicating the wombat population was also recovering, likely in response to the better conditions.

Monitoring of the wombat population through the genetic analysis of hair began in 2000. This technique, called a hair census produces more accurate population estimates than trapping, with much less disturbance to the wombats. This census technique has successfully documented an increase in the wombat population and the

re-balancing of the sex ratio.

The Queensland Government continues to support various northern hairy-nosed wombat research programs that include students from University of Queensland, Charles Sturt University and Central Queensland University.

In 2009, a considerable milestone in northern hairy-nosed wombat conservation occurred, with the successful reintroduction of the species into part of its former range at Richard Underwood Nature Refuge in southern Queensland. With more populations and a greater understanding of northern hairy-nosed wombat conservation needs, focus has moved towards reducing existing threats and intensively managing habitat to protect both populations.

Managing northern hairy-nosed wombat habitat

Potential threats to the northern hairy-nose wombats include:

- uncontrolled fires that can destroy resources

- competition from other herbivores

- predation by introduced species

- introduced weeds that alter and degrade their habitat.

These threats must be managed to help the wombats survive and promote increases in populations.

Fire management

Australian ecosystems have been evolving with fire for thousands of years. The management of fire is challenging, with individual ecosystems requiring specific timing, frequency and intensity of fire. Today, many natural areas require fire management to retain their biological diversity.

A series of controlled burns have been undertaken on Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) during 1997, 1998, 1999, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2019. Controlled burns were also planned in 2000, 2005 and 2018, however, did not occur because of lack of rain. In 2011, 2012 and 2014 controlled burns were undertaken at Richard Underwood Nature Refuge. Compared to wildfires, these burns are typically lower intensity and are undertaken in the cooler months, following rain, to ensure that grass regenerates quickly. There have been two main types of burns:

- large-scale burns outside wombat habitat to reduce fuel loads and promote vegetation diversity

- small-scale burns adjacent to wombat burrows to reduce buffel grass biomass and improve grass diversity.

Food and water

Drought is known to reduce breeding in northern hairy-nosed wombats. Supplementary food and water stations have been installed throughout all wombat-occupied habitat since 2004. There are now 30 water stations on Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) and nine at Richard Underwood Nature Refuge. Remote camera monitoring indicates wombats use water stations regularly, particularly female wombats carrying pouch young and young wombats. Some water stations are surrounded by a mesh box to reduce the competition from other species, particularly large macropods.

Weed control

The management of weeds within Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) is conducted according to the practices set out in the Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) Management Plan.

Control of competitors

Several species can compete with wombats for food, including cattle, eastern grey kangaroos, swamp wallabies and rabbits. Cattle are not only a competitor for food but, at high density or present for an extended time, can also cause damage to burrows through trampling. In 1982, the Queensland Government eliminated this threat to the population through building a cattle exclusion fence surrounding Epping Forest National Park (Scientific).

Monitoring of native competitors is regularly conducted at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) and Richard Underwood Nature Refuge. Macropod breeding levels are high at both sites, due to the freely available water, good pasture cover and lack of predators. This results in unnaturally high densities of competitors. When macropod numbers are deemed detrimental to the wombat populations, culls are undertaken. Managers are also looking at new ways to reduce macropod access to water, which will limit breeding and reduce the need for intervention.

Predator control

In 2004, at least seven wombats were killed by wild dogs at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) highlighting the need to protect the population from predators. Within a year, a fence was built to prevent wild dogs from entering wombat habitat. The fence at Richard Underwood Nature Refuge and the greater bilby enclosure at Currawinya National Park have a ‘floppy top’ which also prevents the movement of feral cats, although feral cats are not considered a major threat to wombats.

The fences at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) and Richard Underwood Nature Refuge are regularly checked and maintained to ensure their integrity. In addition, predator presence is continually monitored inside the fences by regularly inspecting sand plots to detect predator footprints and by remote infra-red cameras. If predators are detected, immediate action is taken to bait or trap and remove the predator from the site.

Monitoring wombat populations

To ensure that management actions are achieving objectives it is essential to monitor wombat populations. The department monitors northern hairy-nosed wombat at two levels. Firstly, it is important to understand changes in the demographics of populations, such as abundance, sex ratio and age. Secondly, it is also important to monitor the health, breeding condition and survivorship of individual wombats.

The wombat populations at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) and Richard Underwood Nature Refuge are monitored using a range of techniques, including:

- trapping of live animals

- visual inspections of burrow entrances

- genetic analysis of hair samples

- remote infra-red cameras.

Live trapping

Live trapping of northern hairy-nosed wombats began in 1985 and was the primary method used to estimate population size at the time.

Trapping typically focuses around wombat burrows to maximise the chance of capture at known locations. The original wombat trap design included a large cage trap with a tripwire of fishing line located in the middle of the trap.

When triggered by a wombat, doors close on either end of the trap, with a radio-signal sent to park headquarters. This initiates an immediate response from the research team, ensuring the captured wombat spends the least amount of time possible in the trap.

All wombats are given a full health check by an experienced veterinarian and samples taken for genetic purposes, health assessments and parasite/ disease identification.

Live trapping wombats has significant challenges. As an intrinsically shy species, northern hairy-nosed wombats show a distinct reluctance to enter traps, with the average trap success between 1985 and 2016 being only 2%. This means 50 traps are needed each night to catch a single wombat.

Various trapping strategies have been trialled to improve trap success. In some areas of Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), fences enclose entire burrow systems with 0.5m sections left open, called ‘gates’. Wombats regularly use these ‘gates’ outside of trapping sessions, however, show a distinct avoidance of them when traps are placed at their openings. Instead, wombats will sometimes remain in burrows or dig out, under the fence, to avoid travelling through traps.

Live trapping wombats has significant challenges. As an intrinsically shy species, northern hairy-nosed wombats show a distinct reluctance to enter traps, with the average trap success between 1985 and 2016 being only 2%. This means 50 traps are needed each night to catch a single wombat.

Various trapping strategies have been trialled to improve trap success. In some areas of Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), fences enclose entire burrow systems with 0.5m sections left open, called ‘gates’. Wombats regularly use these ‘gates’ outside of trapping sessions, however, show a distinct avoidance of them when traps are placed at their openings. Instead, wombats will sometimes remain in burrows or dig out, under the fence, to avoid travelling through traps.

In 2013, an alternative pipe trap design was trialled with some success; however, insufficient time was available to assess its effectiveness completely. In 2020, wombat experts worked with trap manufacturers to redesign the current trap to improve capacity to deploy traps easily and in more varied locations, improve WHS for staff and, reduce resources during trapping. These tests were very successful with an increase in the number of wombats caught to over five times previously recorded levels.

To identify captured individuals, all wombats have a unique number tattooed in their ear. This enables researchers to identify individuals when they are caught repeatedly. Since the mid-1990s, all wombats have also had a microchip, similar to those used on domestic animals, implanted under the skin, between the shoulder blades. During 1999, wombats were also fitted with reflective ear tags, to allow visual monitoring at night, however, this was not continued in subsequent years due to evidence that tags irritated wombats.

Burrow monitoring

Burrow monitoring provides information on activity levels, identifies areas being used by wombats and detects new burrows. During monitoring, burrow entrances are checked for wombat signs, and the activity level of wombats is determined by the presence of fresh footprints, faeces, and diggings. Small prints can provide information on the presence of young animals.

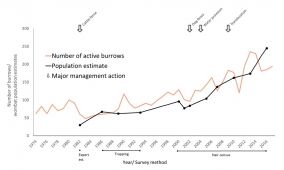

Based on estimates from Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), the number of active burrows is highly correlated to estimated population size, with about one burrow for each wombat. Therefore, total number of burrows can be used as a general indicator of population size.

Hair censuses

Hair censuses are used to estimate the number of wombats by placing strips of double-sided sticky-tape across the entrance to burrows. The sticky-tape collects hair as wombats pass and DNA is then extracted from the hair, enabling managers to classify and determine the sex of individual wombats.

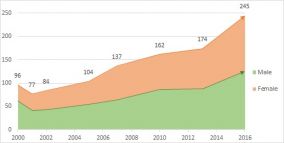

Hair censuses have been conducted at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) since 2000 when 96 northern hairy-nosed wombats were estimated to be in the park. In addition to population estimates, hair censuses provide greater insight into population demographics. In 2000, 64% of the population was estimated as male, which meant only 34 females remained in the only population of northern hairy-nosed wombats.

One year later, the 2001 hair census recorded the impact of a significant predation event by wild dogs, with estimated abundance declining to 77 individuals. Fortunately, although lower in number, the population sex ratio was healthier with males representing 54% of the population.

Since 2001, regular hair censuses have continued to record increases in the abundance of northern hairy-nosed wombats at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific). The population’s sex ratio has also improved with an almost 1:1 ratio recorded in both 2013 and 2016.

Increases in the population were not surprising as considerable evidence of recruitment was recorded since 2005, particularly from remote camera monitoring. Additionally, good summer rainfall, which was experienced in 2006, 2007 and 2010, has been closely correlated to the breeding rate (Horsup et al. 2020).

Since 2010, significant developments in analysis techniques has dramatically improved the accuracy of hair census estimates. Greater precision from new statistical techniques has resulted in a 98.8% chance of accurate identification of individuals at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific). Since the development of new techniques, samples from previous years have been re-examined to produce more accurate estimates.

Based on the most recent hair census and the mean 5% growth rate of the population since hair censusing began in 2000, it is predicted there are about 315 northern hairy-nosed wombats on the planet in 2020.

The department would like to acknowledge the The Wombat Foundation © for their ongoing support in conducting genetic sampling of northern hairy-nosed wombat populations.

Remote cameras

It is difficult to monitor and photograph northern hairy-nosed wombats as they are predominantly nocturnal and very secretive, spending days deep in burrows. Passive infra-red (PIR) cameras provide a great tool to monitor cryptic wildlife such as the northern hairy-nosed wombat.

Since 2005, the department has monitored northern hairy-nosed wombats 24-hours a day using remote infra-red cameras. These cameras record videos and photos when a wombat moves across the infra-red sensor. The cameras are placed where wombats are likely to be active including burrows and water troughs. The cameras have an inbuilt infra-red flash, which is used to capture images at night, eliminating the need to use a white flash that could disturb wombats. Remote cameras are used for gathering data on wombat behaviour and activity, monitoring health and for detecting the presence of young wombats.

Caretaker program

To aid in the management of the day-to-day operations at each site, a volunteer caretaker program has been established. Volunteers work closely with the departmental staff to maintain infrastructure, habitat and monitor the population of wombats.