Ecology

Aspects of wet sclerophyll forest ecology and management

Understanding the ecology of wet sclerophyll forest helps us to manage and restore these systems for carbon and wildlife.

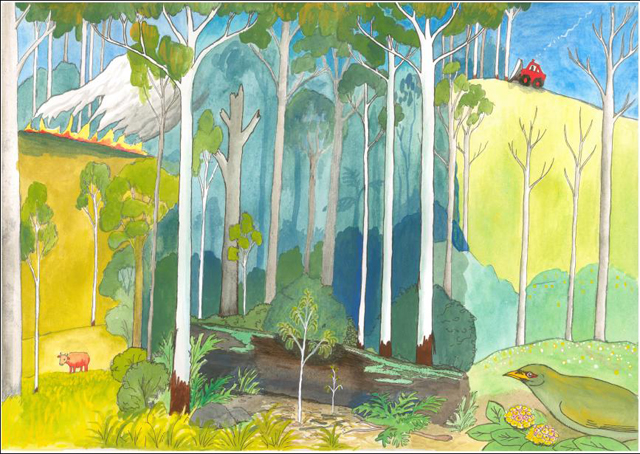

Wet sclerophyll forest—a step towards rainforest

Wet sclerophyll forest is often found growing near rainforest. In many areas, it is only the effect of past fires that prevents rainforest from occupying a site that is currently covered by wet sclerophyll forest.

In the absence of fire, rainforest trees will often invade the understorey of a wet sclerophyll forest, and begin to provide more continuous shade than the canopy eucalypts. This shading prevents the establishment and growth of eucalypt species and eventually results in the transformation of wet sclerophyll forest to rainforest.

Wet sclerophyll forest may also have an understorey dominated by grasses and other herbs. Such grassy understoreys typically depend on frequent low intensity fires to suppress the recruitment and growth of shrubs (including rainforest species).

Regeneration

Wet sclerophyll eucalypts are relatively fire-sensitive, but are also highly dependent on fire for their survival. They are more easily killed by fire than most other eucalypt species, but they also germinate and grow best after disturbance (such as fire).

Most eucalypt species have features that allow them to survive hot fires (such as thick bark and lignotubers), but these features are absent, or only poorly developed in the canopy species of wet sclerophyll forest. Two of the most widespread wet sclerophyll eucalypts that occur in Queensland do not develop lignotubers (the flooded gum E. grandis and blackbutt E. pilularis). While the flooded gum can be killed by relatively low intensity fire, blackbutt may recover through epicormic shoots.

Most wet sclerophyll eucalypts have small seeds that do not survive in the soil for long. Wet sclerophyll eucalypts also tend to need a lot of light to grow, and their seeds may have trouble germinating and surviving on undisturbed forest soil, particularly when thick leaf litter is present.

The regeneration of wet sclerophyll forest in southern Australia is often associated with high intensity crown fires which kill the mature canopy trees (for example, the 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria). Mass germination, and rapid growth of seedlings can occur if good rains follow these fires.

Fortunately, high intensity crown fires are a rare event in Queensland, presumably because of the wet summers here. The wet sclerophyll eucalypts of Queensland can regenerate after high intensity fires by using similar strategies to their southern counterparts, but regeneration is most often triggered by more patchy, low level disturbance (e.g. low intensity surface fire, or mechanical clearing).

North Queensland

In north Queensland, wet sclerophyll forest forms a narrow strip along the western edge of the rainforest. It seems that fires of the intensity required to generate and maintain larger stands of wet sclerophyll forest seldom occur in the Wet Tropics.

Rainforest plants have invaded the wet sclerophyll forest in many areas, and canopy eucalypts do not appear to be regenerating. There are concerns that wet sclerophyll forest in north Queensland will be replaced by rainforest. This is likely to disadvantage species that rely on wet sclerophyll forest for food and shelter (e.g. the yellow-bellied glider Petaurus australis).

The biology of wet sclerophyll canopy trees

Seedlings of E. grandis and E. pilularis can sometimes resprout from their base if damaged by grazing or factors other than fire, but plants up to 3m high can be killed by even low intensity fires. These seedlings can persist in the understorey of wet sclerophyll forest for many years, and are capable of rapid growth when released from competition with neighbouring plants. It may be beneficial to clear dense shrubs to encourage the growth of eucalypt seedlings, especially weedy shrubs such as lantana.

Fire

Wet sclerophyll forest in Queensland can be maintained with patchy low intensity fire or mechanical disturbance (e.g. disc ploughing or stem cutting). Extremely hot fire should be avoided as it can eliminate both fire-sensitive eucalypts and understorey species, and exhaust soil seed stores, if it occurs at relative short intervals (e.g. less than 10 years). It can also lead to the dominance of fire-tolerant plants, both native (e.g. acacias and bracken) and exotic (e.g. lantana).

Regular low intensity fires can be used to reduce fuel loads, manage weeds such as lantana, and maintain grassy understorey in some Queensland wet sclerophyll forest. Yet frequent fires can have negative effects on tree growth and survival, and on soil nutrients and microbes.

It is unclear whether patchy low intensity fire or mechanical disturbance are viable methods of regenerating wet sclerophyll eucalypts in northern Queensland.

Dense understorey vegetation

A dense layer of understorey shrubs and trees can prevent the germination and growth of wet sclerophyll eucalypt seedlings by shading them.

Fire can be used to prepare a site for direct seedling, by reducing competition from fire-sensitive plant species. But it can also encourage the germination of fire-tolerant shrub species such as Acacia and Dodonaea if their seed is present in the soil, and these may successfully out-compete the young eucalypts.

Eucalypts have long lifespans (100+ years), so a high rate of seedling establishment (e.g. every 1–10 years) is not necessary to ensure the replacement of old trees when they die. Therefore the patchy disturbance of understorey vegetation to allow tree establishment may only be needed if tree replacement is obviously being suppressed over an extended period of time.

Bell Miner Associated Dieback

Bell Miner Associated Dieback (BMAD) causes the loss of leaves and death of branches in wet sclerophyll tree species, such as E. saligna and E. grandis. It can also result in tree death, and it is not uncommon to see groves of dead eucalypts where colonies of bell miner birds are present.

The exact causes of Bell Miner Associated Dieback remain unclear, as numerous factors are apparently associated with the phenomenon. These include disturbance by logging, changes to forest structure, weed invasion, altered fire regimes, and the high abundances of psyllid insects (Glycaspis species) and bell miner birds (Manorina melanophrys).

The many interactions between these factors add even more complexity. For example:

- The Glycaspis psyllids feed on the sap of canopy eucalypts, and produce a sugary cover (lerp) where they are attached to the leaves. Bell miners feed on the lerps, and unlike other birds, the bell miners appear to allow the survival of psyllids by dislodging the lerp with their tongue, and not harming the insect. Bell miners are also highly territorial and discourage the presence of other insect-eating bird species. This may allow the psyllid population to multiply, providing the bell miners with more food, but also increasing the impact of the psyllids on their host trees.

- High levels of plant stress may also produce a negative feedback loop, as stress can increase the nutritional quality of the trees’ sap, which further helps the psyllids and increases their negative impacts on the trees.

- Canopy cover is often lost when trees decline in health, and this increases the amount of light penetrating the forest. Understorey shrubs can then grow more vigorously when more light is available. In many areas affected by Bell Miner Associated Dieback there are also dense thickets of understorey shrubs, such as lantana. As discussed above, a dense layer of understorey shrubs can suppress the germination and growth of mid and upper-canopy plant species, and this can lead to a change in forest structure. This appears to suit the bell miners, who prefer to nest in thick vegetation between 2m and 5m in height, and are often associated with areas that have a more open canopy and dense shrubs and small trees.

Altered fire regimes have been put forward as another cause of Bell Miner Associated Dieback, but no consensus has been reached on what these are, and which fire regimes should be reinstated.

Although there are many theories about the causes of Bell Miner Associated Dieback, and how it should be managed, many of these are not based on scientific evidence. More research and adaptive management are needed to better diagnose and treat the problem. However, a recent trial involving the removal of lantana by applying herbicide with a splatter gun has produced some promising results. There is still much to understand about Bell Miner Associated Dieback and its treatment, but if the sites are also infested with lantana, it seems that lantana removal may be a good place to start.