The Food Act provides a suite of enforcement options. The enforcement action taken by a local government should be graduated and proportionate to the severity of the non-compliance observed and any history of non-compliance. When considering enforcement data, it is important to note that in addition to enforcement actions, local governments use non-punitive actions such as education to assist food businesses achieve or maintain compliance with the Food Act. This report does not capture information from local governments in relation to other strategies used.

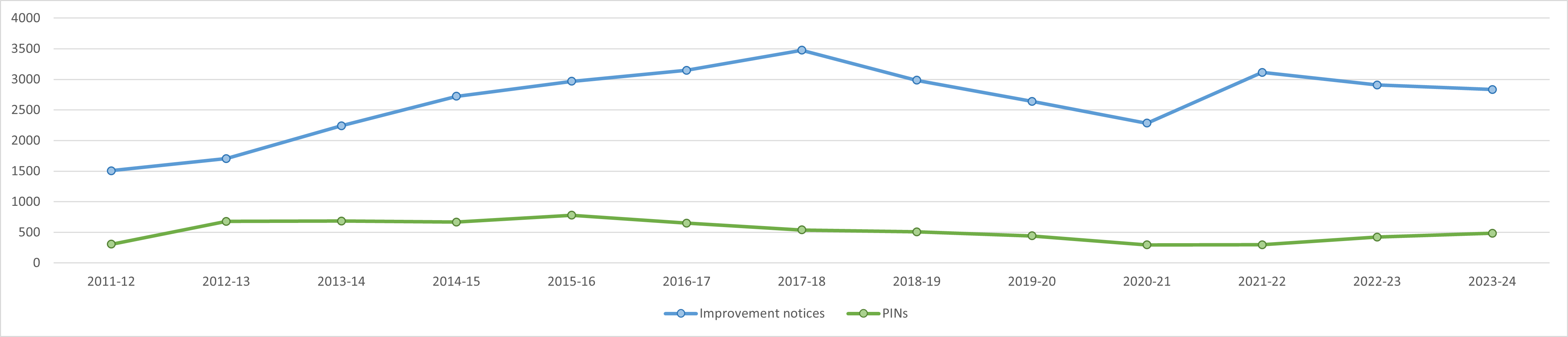

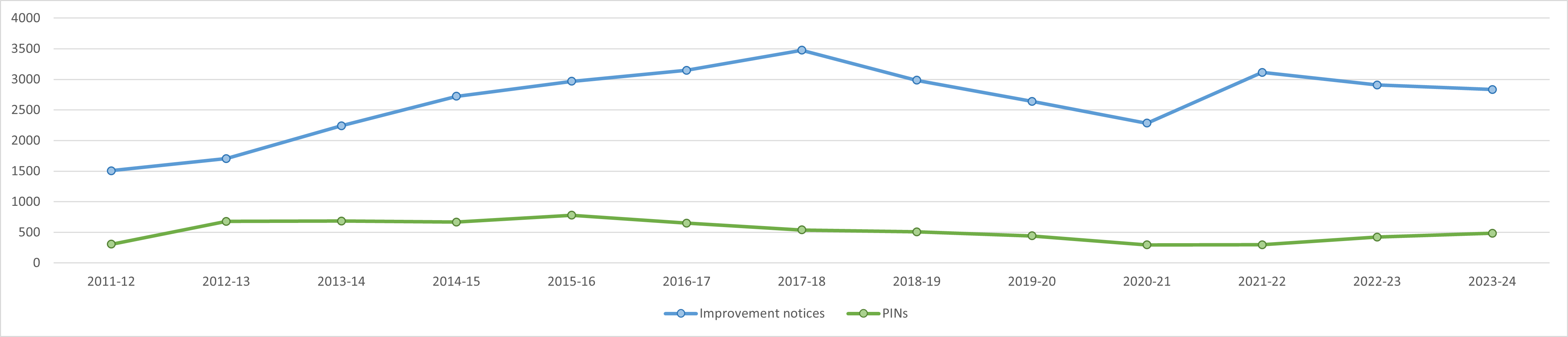

Consistent with previous years, the main type of enforcement activity undertaken by local government was the issuing of improvement notices, followed by prescribed infringement notices (PINs) as the second most common enforcement tool, as represented in the figure below.

Improvement notices

Improvement notices are utilised by local governments to address a variety of non-compliances within a food business. This may include issues such as the need to remedy cleaning, maintenance or structural contraventions or unsafe food handling practices. Improvement notices must provide food businesses with a reasonable timeframe to remedy any stated non-compliance.

Improvement notices remain as the most utilised method of enforcement. The number of improvement notices issued in this reporting period (2,834) is similar to 2022-23 (2,908).

Prescribed infringement notices

Prescribed infringement notices (PINs) may only be issued for offences that fall within the guidelines for eligible offences that have been acknowledged as PIN offences under the State Penalties Enforcement Regulation 2014. Only certain offences under the Food Act have been prescribed as PIN offences.

PINs can be issued when offences pose a moderate threat to human health and safety, or where there are indications of previous, current and ongoing non-compliance, such as failure to comply with a licence condition (section 51(1)) or failure to comply with the Food Standards Code (section 39(1)). The penalty unit values for PINs are relative to the severity of the offence.

While the issuing of PINs remains the second most frequently used type of enforcement activity, the number of PINs issued within the 2022–23 reporting period (486) increased by 15% from 2022–23 (421).

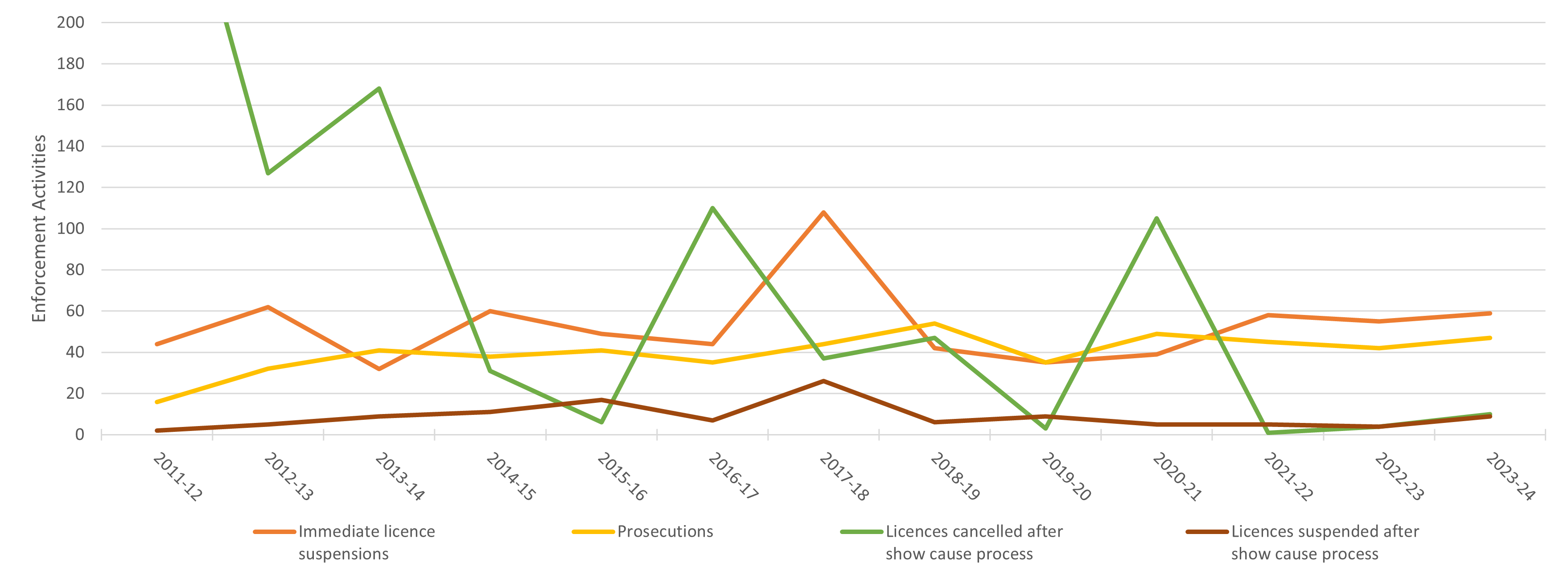

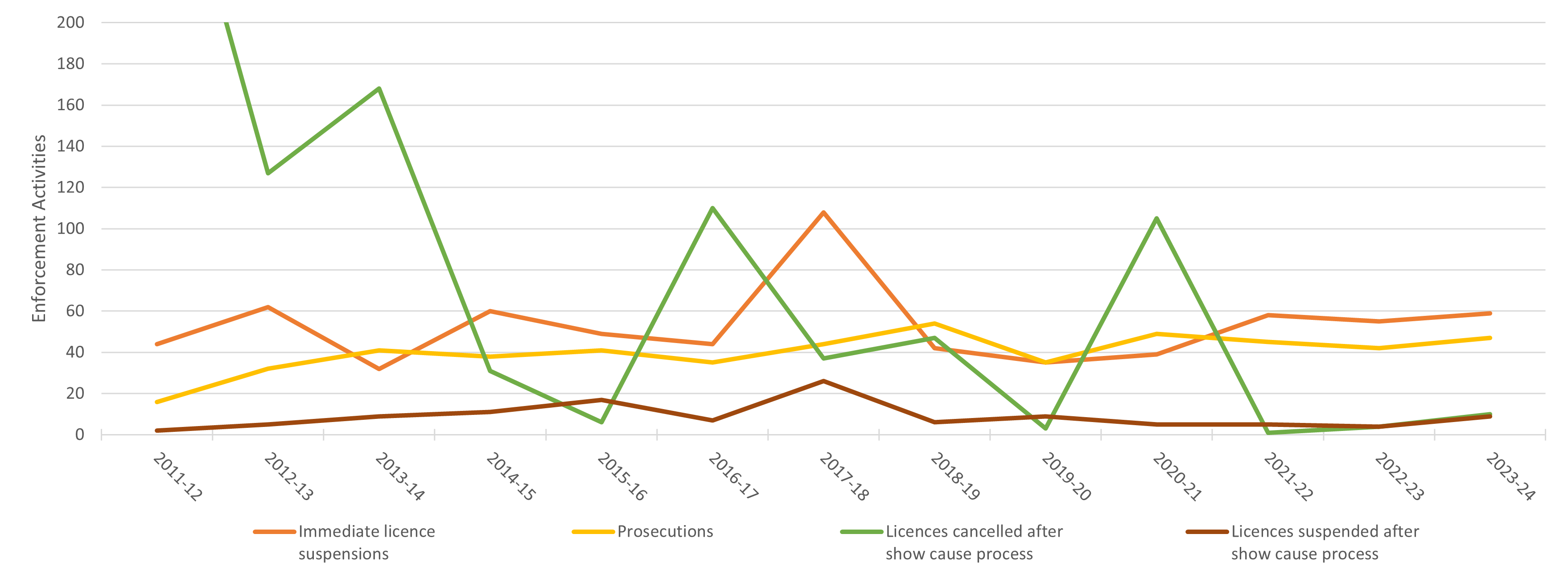

The annual trend in relation to other enforcement activities undertaken by Queensland local governments are shown in the figure below.

Suspension and cancellation of a licence

Section 78 of the Food Act allows local governments to suspend or cancel a licence when the licensee:

- is not, or is no longer, a suitable person to hold a licence

- has not complied with the accredited food safety program and the non-compliance is likely to result in a high risk to public health or safety

- has a licence issued under false or misleading representation.

Licences can be suspended or cancelled following a show cause notice. Local governments can use the show cause notice provisions prior to taking proposed action such as suspending or cancelling the licence.

A total of 94 show cause notices were issued during this reporting period, resulting in nine licence suspensions and ten cancellations.

Licences may be immediately suspended if a ground exists to suspend or cancel the licence and it is necessary to suspend the licence immediately because there is an immediate and serious risk to public health or safety.

During this reporting period, there was a total of 59 immediate licence suspensions, 61% (36) of which were issued by Brisbane City Council.

The number of food businesses that surrendered their licence was 641, 42% more than in 2022–23 (453).

Seizures

An authorised person has the power to seize a thing under the Food Act in certain circumstances, for example as evidence of an offence under the Food Act. A total of two seizures were undertaken in 2023–24, consistent with the past three reporting periods.

Prosecutions

Prosecutions are usually initiated if there is a high threat to human health and safety, or if there is a known or expected ongoing non-compliance. Consequently, prosecutions are the least common, most resource-intensive enforcement tool utilised by local government.

For this reporting period, a total of 47 prosecutions were undertaken, all of which were undertaken by Brisbane City Council.