Patrick Smythe

Vietnam War reunites two brothers

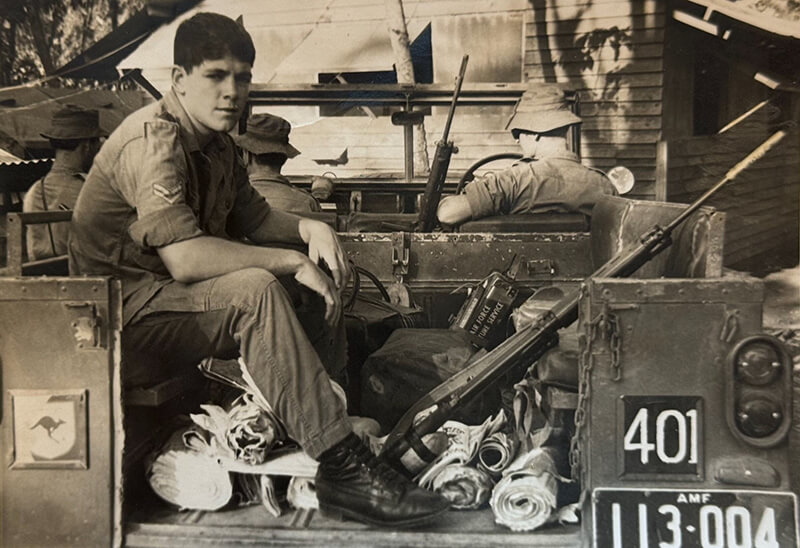

It was September 1968 when 20-year-old Patrick Smythe joined a convoy heading to Ba Ria in Phuoc Tuy province, former South Vietnam, as a ‘shotgun’ – the person responsible for sitting next to and protecting the driver of the vehicle.

He was doing a laundry and ice run, as he and his comrades had done many times before.

This particular day, the convoy included an armoured personnel carrier (APC) and a large American vehicle similar to a troop carrier, which was leading the convoy.

Mr Smythe still recalls the memory vividly.

“The American vehicle hit a landmine which killed the driver and his shotgun, and from there our drivers were skilled in taking up herringbone positions, angled ready for a ground assault.” he said.

However, nothing occurred and a Dedicated Untiring Service to our Forces (DUST OFF) chopper was deployed to administer first aid to the injured and to retrieve casualties.

“I spotted a fellow on the back of the trucks, and I thought ‘gee that looks like my brother’. So, I got onto that vehicle, and it was him – that was his first week in Vietnam.”

It was a family reunion, and a very unusual one at that, with the military custom being that a family would normally have only one son in a war zone at the same time.

“Mum had told me that Brian, my brother, had been called up as a national serviceman. He was refused as he was colourblind.

“I didn’t know he was part of the regular army. That’s why I was so surprised when I saw him on the back of his truck.”

For the rest of his deployment Mr Smythe and his brother, Brian, 22, would see each other regularly, often at the Doug Plain Club, in Nui Dat, where the Australian Taskforce was stationed in Vietnam.

Named after one of the Australian soldiers lost in combat, the club had its own canteen, table tennis table and pool table.

Mr Smythe celebrated his 21st birthday there with his brother.

It was a far cry from his upbringing in the rural town of Gatton in Queensland’s Lockyer Valley where Mr Smythe spent his downtime “fishing, killing snakes and everything young boys do.”

He attended the Gatton Convent from Grade 1 through to Grade 10, passing what was then known as ‘Junior’, or Year 10.

As a fresh-faced 17-year-old, the Commonwealth Bank made him an offer to join them shortly after as a trainee teller.

It was when a couple of his unemployed friends had the idea to enlist in the army for the war in Vietnam that Mr Smythe’s life took a different turn.

“I didn’t like the bank anyway,” he said.

“I think because my mates wanted to do it, I agreed. I think it was the fascination of going overseas.”

Both Mr Smythe’s parents had military ties.

“Mum was in the Woolstores, preparing and supplying the uniforms to send overseas,” he said.

“My dad served in New Guinea as a soldier.”

For Mr Smythe joining the military was a natural progression.

He boarded a train to Brisbane to enlist and, to his surprise, he was approved but his friends were not.

From there he was sent to Kapooka in the south-west of Wagga Wagga, New South Wales – home of the Blamey Barracks, where the Army Recruit Training Centre still conducts its operations.

Mr Smythe completed three months of full-time recruit training followed by three months at the Infantry Training Centre in Ingleburn, Sydney.

He was then posted to the 8 Royal Australian Regiment (8 RAR) in Brisbane.

“During that time, I did 12 months on the Demonstration Platoon at Canungra, which was the Jungle Warfare Centre where we showed the young fellas how to do things.”

From there the Battalion was deployed to Malaysia in September 1967 and was mobilised to Malacca in the south-west of the country.

In May 1968, Mr Smythe was transferred to Vietnam where he would spend the next 13 months.

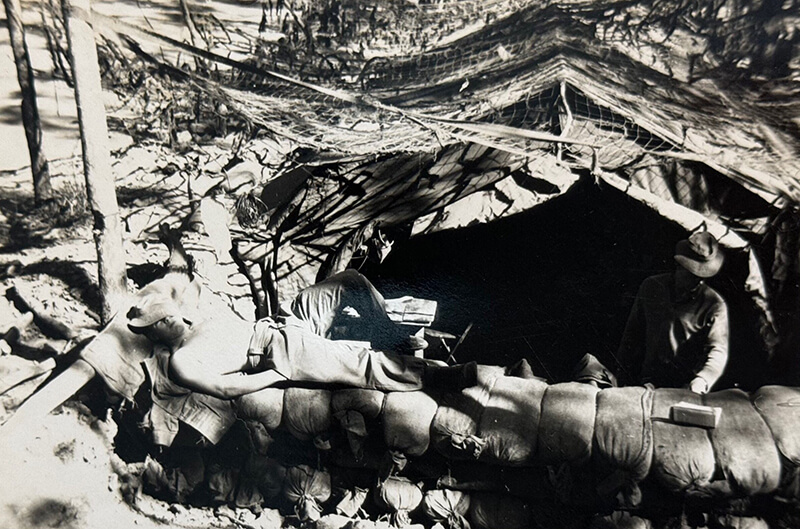

His first operation was Fire Support Base Coral in the Bien Hoa province, which came under attack from the North Vietnamese Army because the base was positioned on their supply route to Saigon.

“My service in Vietnam was unusual whereby I was posted there from 8 RAR as a reinforcement and ended up at HQ Coy 1ATF with a makeshift section and almost immediately was sent out on Fire Support Base Coral to secure the perimeter along with Companies from 1 RAR and 3 RAR.

“We were some of the first to occupy the base with little time to dig in and the rest is history.”

Among other jobs, he was often a shotgun in convoys and did other general duties around the taskforce such as night ambushes and Taskforce Area of Operations, or TAOR patrols, conducted at any time of the day or night.

“When I got posted to Vietnam, the guy I was replacing wasn’t going home for three or four months so I was superfluous.

“What used to happen to people like me, is they’d use me as a shotgun on convoys. Any irregular type of job around the taskforce – I’d seem to get it.”

By then, Mr Smythe had been promoted from a Recruit to a Private, to Lance Corporal, and on to Corporal.

Upon arriving in Vietnam, he held the position of Corporal Section Commander for three months and had subordinates.

“As a young soldier with a rank higher than guys older than me, I grew up pretty quick.

“I had to dig deep as I was two or three years younger than some of my men and it was a big difference in those days.”

He recalls having to charge a soldier once for destruction of Commonwealth property for continually cutting off the brim of his bush hat after being warned several times.

The living conditions are also hard to forget.

“My home was quite primitive. The mattresses were the most uncomfortable. They were dirty and dusty – the dust would just come in if a vehicle arrived.

“We had no hot water, so we’d light a fire under a 44-gallon drum of water.”

Contact with his family was also challenging with no telephone on site.

“The mail took forever. Mum prepared biscuits and by the time we got them we’d have to bin them anyway.”

Despite this, the morale amongst those at the Taskforce was generally high, according to Mr Smythe.

“Married national servicemen had the most issues. A letter from home and they started drinking too much. Ninety-nine per cent was good.”

Time off was also a morale booster.

“Occasionally I went on a convoy to Vung Tau which was beachside – the Americans had a rest and convalescence resort. I went about four times.”

Onsite was the Peter Badcoe Club, named in honour of the Australian Victoria Cross recipient.

“We went for the day, swam in the ocean, had a few grogs and jumped on the truck and came home.”

Outdoor movies were another welcome break from war.

“They were shown in a tank shelter set up. A few times a week we had outdoor movies where you took your own chairs and your own couple of beers, and away you went.”

Cricket matches also brought relief.

“We had four games of cricket. The artillery up the road might put a team up and we would put a team up.”

The most positive outcome from Mr Smythe’s deployment was the friendships he made.

“There were a few of us that were very close when we came home. I still keep in contact – 55 years later, we correspond regularly. We stay at each other’s house and visit.”

He says it was in Vietnam that he learned about being a team player, mateship, and loyalty.

He also gained some disciplines that would serve him well for life – being on time and being tidy.

“My life was influenced greatly with my army service, in particular with the disciplinary measures, time issues and trying to make the right decisions under pressure.”

The most challenging aspect was the attitude of Australians upon returning from the war.

“I didn’t realise there was such animosity and hatred for Vietnam soldiers.”

Having arrived at Brisbane Airport excited and ready to surprise his parents after a long time away, he received a reception he wasn’t expecting.

“I got a taxi from Brisbane Airport that cost me a week’s pay. We were heckled at the airport.

“I came home as a Sergeant and my dad said to me ‘son, take off your uniform before you go to the pub.’

“You were conspicuous with short hair.”

Upon returning, he was given a disability pension due an injury sustained during the war after an artillery round was dropped close by, perforating his eardrums.

“I was in Vung Tau Hospital for a week. [My ears] were still ringing when I woke in hospital.”

With a couple of months’ leave up his sleeve, Mr Smythe took up a job chipping the weeds out of cotton, prior to taking up his next appointment as a Sergeant in Rockhampton as part of the 42 Royal Queensland Regiment (42 RQR).

During his time there, he had another negative experience tied to his time serving in Vietnam.

“I went to the Biloela RSL in uniform on ANZAC Day in 1973. I was the Guard Commander for the ANZAC Day March.

“Some person came over and started jiggling my medals and saying Vietnam was a skirmish.

“That really hurt me. They threw him out of the RSL.

“That goes back to the hatred people had at the time.”

When asked what Vietnam Veterans Day means to him, Mr Smythe indicates that he has more respect for Remembrance Day.

“[Vietnam Veterans] Day is a great day if I’m with some of the fellows I was overseas with.”

Mr Smythe eventually entered the civilian work force after he took his discharge from the army in 1972, where he returned to his pre-army occupation as a banker and finance company employee, retiring in 2000, having served 28 years in managerial positions.

He has also received several awards following his military service, including the Australian Service Medal for Vietnam, the Australian Service Medal of Malaysia, the Australian Defence Medal, the Active Service Medal, and the Vietnamese Campaigns Star.

This is in addition to two Unit Citations for Gallantry – one for Fire Support Base Coral, and one from the Republic of Vietnam.

Mr Smythe has returned once to Vietnam since he served in the war, taking a day trip there as part of a cruise holiday, but his memories of the war proved too challenging to enjoy it.

He now lives with his wife, Lorelle, in an over 50s community in Queensland where about a dozen of the residents are ex-servicemen.