Surveying process

Land surveys

The main intention of land surveys was to positively identify and mark as clearly and permanently as possible boundaries of land for the purpose of establishing ownership. Plans of such surveys were prepared from details recorded by the surveyor in his field notes.

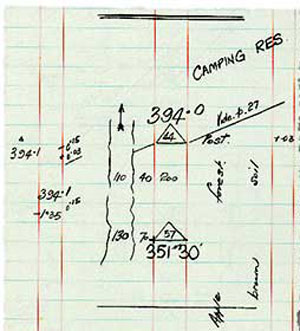

All measurements taken during the day were recorded in a field notebook (bearings and distances). Also recorded was the vegetation and soil type. This allowed intending selectors to judge the type of land they were selecting.

It was at night in the tent that the surveyor would calculate and plot the information from his field notebook.

Significant information was extracted including:

- dimensions (bearings and distances) and area

- marks placed or found (pegs, survey posts, iron pins, reference trees, etc.)

- accurate location (by traverse) of watercourses forming part of the boundary

- description of country and location of improvements.

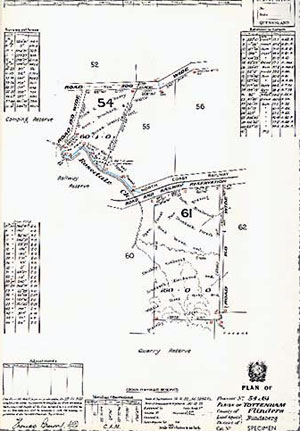

From the surveyor's measurements in the field, a survey plan was drawn.

Plans of survey were the basis for the issue of deeds and leases, the gazettal of reserves and the compilation of cadastral maps.

The survey plan would be lodged with the Survey Office or its equivalent for crown/leasehold land and with the Land Registry (Titles Office) for freehold land.

Verifying the surveys

Although the Surveyor-General's Department had its own staff of salaried surveyors for work on the crown lands of the colony, their numbers were never enough. This was especially the case in times of high demand for crown lands and so contract surveyors had to be employed. It then became the task of the salaried surveyors to examine the work submitted by the contractors.

If the surveyors work was found wanting they were often dismissed, WA Tully, Surveyor General, reported in 1879 in his Annual Report:

‘Surveying is a class of work in which great dependence has to be placed on the intelligence, honesty, and conscientiousness of the surveyor. The majority of those employed by the Department, I am happy to say, give little or no trouble. They take an interest in their work, and it is a pleasure to them to execute it in a creditable way. There are others, however, upon whom the same reliance cannot be placed. The inspecting surveyors have to make periodical examinations of their work on the ground, and were it not for this liability to inspection, I am afraid it would be very difficult to maintain the requisite degree of accuracy in the field. In consequence of errors in their work, I have dispensed, within the last twelve months, the services of several licensed surveyors. It is a severe step to take, but the importance of having reliable men to effect the surveys is so essential to the economical and satisfactory working of the Department, that I feel it necessary to take this course whenever a gross case is reported.’ (Tully, WA 1879, Annual Report)

When challenged, surveyors gave some interesting explanations as to their results. When explaining to the examining surveyor why his short distances were better than his long distances Surveyor W Fryar, in 1871, advised:

‘In the first portion, referred to No 206, Moggill, the greatest difference is in the west boundary 6494 by Exg Surveyor and 6445 by myself. The difference is so small that it could scarcely be sworn to in rough country, indeed when you consider that all the danger of litigation between adjoining properties, and claims against the government would lie against short measurements, it will be questionable whether the extra 1½ inches is not rather a safeguard than otherwise ... And although my chainage is not by any means perfect, I am strongly of opinion that with all its faults, it is better and safer than that of the examining surveyor who if not absolutely correct, errs on the wrong side, whereas I am always on the right side, as I know of no case yet where he has reported my given lengths as being too long.’ (Fryar, W 1871, File SUR/A/1871/3783, Queensland State Archives)

The form of the survey examination was explained in the Annual Report of 1889:

‘The staff of salaried surveyors is not sufficiently large to make a rigid examination of every surveyor's work in detail. Each survey, however, is subjected to a severe mathematical examination in the drafting branch, and the work in the field is inspected as frequently as possible. The plans are checked in every possible way, and suspected inaccuracies reported to the staff surveyors for examination at the earliest opportunity. Each surveyor knows his work is liable to examination at any time, and if found below the recognised standard of excellence, or charged for at too high a rate, he is well aware that no further work will be entrusted to him. By this means wholesome check is kept upon bad work, and it is confidently believed that there is very little faulty work now done for this department, and there will be less in the future.’ (Surveyor General 1889, Annual Report)

Related links

- Learn about Queensland’s historical surveying processes.

- View images of instruments and equipment used to survey and map Queensland.